Part II: Translations

The Bible cannot be read literally because what I buy today is a translation from centuries ago. Even when reading English as a native speaker, it is not always possible to determine what the author means or intends. We ask these types of questions. Is the writing a translation from another language? Has the writing been updated from an earlier version of English? Did someone who speaks English elsewhere in the world add references that Americans might not understand? Biblical translations are even more challenging.

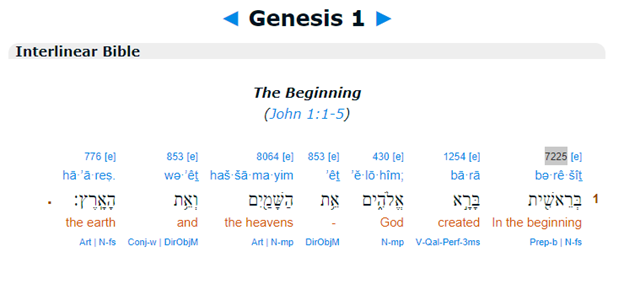

Translating Hebrew into English

Scholars who have translated Biblical Hebrew into English or other modern languages, face a few challenges. First, these scholars are referring to old manuscripts, some of which differ from one another. Second, Hebrew reads right to left as we see in the first line of the Bible from Genesis above. Third, different versions of Hebrew can be found in the writings as well as some Aramaic and koine Greek.

If a person wants to become a Scripture scholar who specializes in the Hebrew Bible, it helps to have strong linguistic skills.

The challenge of mastering multiple biblical languages in addition to others like Ugaritic should not make you think that no one knows what the original scripture writings say.

Early Biblical Translations

The early biblical translations were Greek and Latin.

Septuagint

Jewish scholars translated the first five biblical books into Greek in the third century BCE. The name of this version is the Septuagint because apparently seventy scholars worked on the translation.

Vulgate

Christianity grew rapidly in the Roman Empire, where the the use of Greek was lessening and many people spoke Latin. Some people translated the Bible into “common” Latin: the Latin used by everyday people. Note that people in the U.S. use the word “vulgar” to mean that something is inappropriate or rude. In the ancient world, vulgar was an adjective that referred to language understood by everyone.]

Because there were various Latin translations in circulation, Pope Damasus, in the late fourth or early fifth centuries, asked St. Jerome to revise the four Gospels from a widely used Latin translation called the “Vulgate” because it used common Latin. St. Jerome did so, working with Greek texts and comparing various Latin translations. The saint went on to translate other books in the Bible and to oversee others’ work. The resulting common Latin translation is usually called the “Vulgate.” Interestingly, the Vulgate was not approved by the Catholic Church for more than one thousand years. In 1546, the Council of Trent gave its official approval to the Vulgate. Who said that the Catholic Church moves quickly?

St. Jerome was uniquely qualified to translate as he was “fluent” in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew; he was also familiar with Arabic, Syriac, and Aramaic. The Vulgate was in use for centuries. Various scholars used the Vulgate to translate the Bible into additional languages. Gutenberg used the Vulgate on his newly invented printing press.

The Bible in the Modern Day

In the twentieth century, Pope Pius XII (1939 – 1958) wrote an encyclical mandating that any future bibical translations of the Bible must be based on the original languages.

As you can imagine, any translation of the Bible requires careful scholarship. Knowing ancient languages is one part. Understanding cultural features of different eras helps scholars understand what the biblical texts say.

In addition to figuring out what an author meant centuries ago, a translator must then figure out how to convey the same meaning in the new language. If you were to look at Bibles back several centuries, the choice of words in an English translation would be different because some words fall out of circulation while others are introduced into a language. Meanings change. Look at the word “vulgar”!