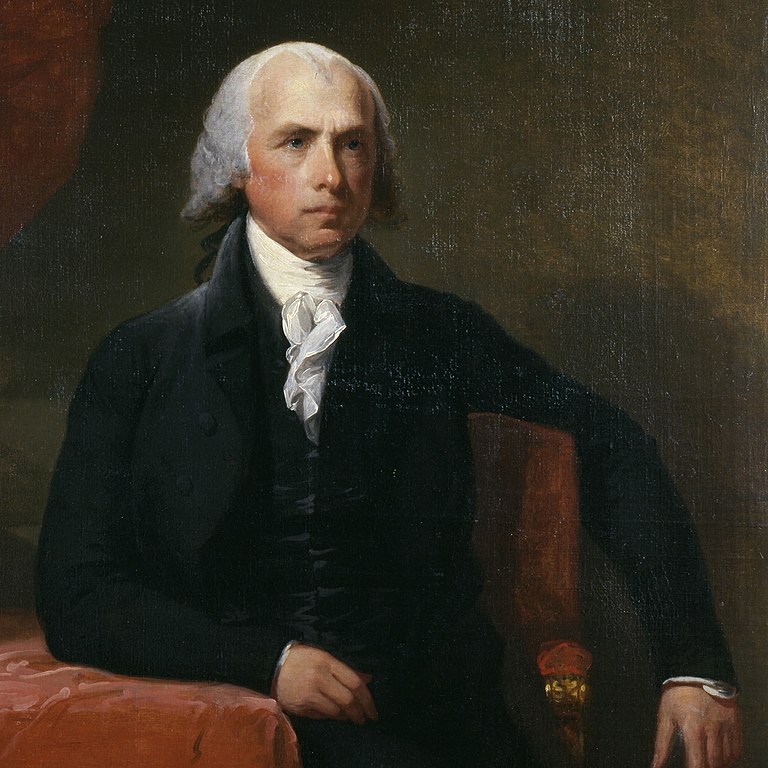

Among the U.S. founding fathers, nobody cared more about religious freedom than James Madison. Madison (1751-1836), America’s fourth president, was deeply involved in crafting the U.S. Constitution and promoting its passage. His peers called him “the father of the Constitution.” He was the chief author of the first ten amendments to the Constitution, also called the Bill of Rights.

And whenever people complain about the many Supreme Court decisions enforcing the separation of church and state — such as Engel v. Vitale (1962) or Abington School District v. Schempp (1963), it’s mostly Madison they’re complaining about. It’s Madison’s words in the First Amendment that judges cite when they put limits on prayers in public schools, for example. But Madison wasn’t hostile to religion; he was trying to protect it.

Madison’s views on religious freedom were well developed before the Constitution was written. Let’s take a look.

James Madison, Patrick Henry, and Religious Taxes

For a brief period period that ended in 1789, when the Constitution went into effect, the newly independent United States was organized as a confederation of sovereign states. During that time James Madison served in the Virginia legislature. In 1784, another legislator, Patrick Henry, proposed a bill that would require Virginians to pay a tax assessment that would go to a Christian congregation of their own choosing. Similar religious taxes had been imposed in other states.

Madison was adamantly opposed to the assessment. He and Patrick Henry (whom you might remember for the “Give me liberty or give me death” quote) nearly went to war over it. But then Henry was elected governor of Virginia, which took him out of the legislature.

Madison’s Argument Against the Religious Tax

In 1785, Madison wrote and submitted to the legislature a text called “Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments.” (You can read it all here, beneath the rather long Editorial Note. Just scroll down if you don’t want to read the note.) Here are the important points. (We’ll have to overlook Madison’s 18th century tendency to only talk about men and not women. I’m sure he heard from his wife, Dolly Madison, about this.)

In Part 1, Madison argues that religion is a matter of personal conscience. People must be free to decide religious truths for themselves. “The Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate. This right is in its nature an unalienable right. It is unalienable, because the opinions of men, depending only on the evidence contemplated by their own minds cannot follow the dictates of other men.” Madison goes on to write that as a matter of personal conscience, religion must not be dictated and controlled by the majority opinion of society. He warns us that majorities may trespass on the rights of minorities.

In Part 2, Madison says, “Because if Religion be exempt from the authority of the Society at large, still less can it be subject to that of the Legislative Body.” In other words, the government must be constrained from encroaching on matters of personal conscience, like religion. “The Rulers who are guilty of such an encroachment exceed the commission from which they derive their authority, and are Tyrants. The People who submit to it are governed by laws made neither by themselves nor by an authority derived from them, and are slaves.”

Why Laws Favoring Religion Invite Tyranny

In Part 3, Madison warns that while people who make laws favoring their religion may have benevolent intensions, they need to understand that future generations may use the same government authority against their religion. In other words, if we give government the power to levy taxes to benefit churches — or to dictate what prayers are said in public schools — at some point citizens may find themselves paying taxes to churches very different from theirs. Madison wrote,

Who does not see that the same authority which can establish Christianity, in exclusion of all other Religions, may establish with the same ease any particular sect of Christians, in exclusion of all other Sects? that the same authority which can force a citizen to contribute three pence only of his property for the support of any one establishment, may force him to conform to any other establishment in all cases whatsoever?

In other words, if the government is allowed to have the legislative power to support Christianity and ban other religions, at some point in the future a majority faction of, say, Lutherans might cause the government to discriminate against Christian churches that are not Lutheran. The obvious remedy to this is to deny the government the power to favor one religious sect over others.

Note that Justice Hugo Black quoted this same passage in his majority decision in Engel V. Vitale, which in 1962 found group recitations of prayers in public school classrooms to be unconstitutional. If the government has the power to dictate that children recite Christian prayers in school, it also has the power to have them recite non-Christian prayers. The simplest way to prevent this is to deny government that power.

Neither Church Nor State Need This

Madison continued through several more parts, and I’m not going to discuss them all. One of the more interesting points, restated several different ways, is that Christianity surely doesn’t require government favors in order to flourish. Indeed, there are many examples from history showing us that religious institutions have been badly corrupted by political power.

And, likewise, a government doesn’t benefit in any way from taking on religious duties. In the past, government meddling in religion has not turned out well. “Torrents of blood have been spilt in the old world, by vain attempts of the secular arm, to extinguish Religious discord, by proscribing all difference in Religious opinion,” Madison wrote.

The religious assessment tax did not become law.

Madison’s Legacy of Religious Freedom

A year after Madison wrote the Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments, the Virginia legislature passed the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. This statute was largely a project of Madison’s close political ally Thomas Jefferson, and it makes many of the same points. I plan to discuss the statute in a future post. Both Madison and Jefferson believed deeply in both freedom of conscience and the principle of separation of church and state.

Both Madison and Jefferson argued that genuine religious freedom requires separation of church and state. If government has the power to dictate what prayers are said in schools and at public events, for example, it has the power to interfere with individual religious conscience. Justice Thomas Clark made the same point in his majority opinion in Abington School District v. Schempp, which determined that classroom Bible readings and recitations of the Lord’s Prayer in public schools is unconstitutional.

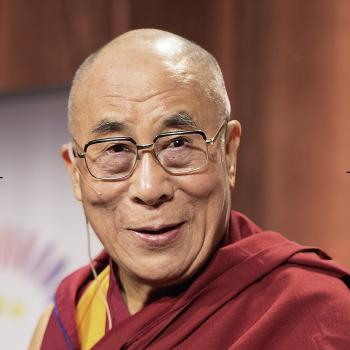

And for any parent who doesn’t understand the wisdom of this, I’m happy to show up at your child’s school to lead the class in a rousing chanting of the Nembutsu.

The First Amendment

In 1789, James Madison wrote the First Amendment to the Constitution, which is,

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Most people like the free exercise of religion clause, and the freedom of speech clause, and the right to assemble clause, etc., but the establishment of religion clause is something else entirely. Many religious people don’t like it one bit. That’s the clause that restricts government from engaging in religious practices. It’s the clause that Thomas Jefferson said put a “wall of separation between church and state.” But perhaps if the critics understood it better, they’d change their minds.