What is the meaning of faith? In particular, what is the meaning of the word faith in a religious sense? This is important, because “faith” often is used as a synonym for “religion.” Religious people are said to be “people of faith” who are following a “faith tradition.” Because religion is a hard word to define, understanding the meaning of religious faith would be a big help in understanding it.

The 20th century Christian theologian Paul Tillich said, “There is hardly a word in the religious language, both theological and popular, which is subject to more misunderstandings, distortions and questionable definitions than the word ‘faith.'” (Dynamics of Faith, 1957) So let’s try to see where the confusion lies.

Is Faith “Belief Without Evidence”?

You’ve probably heard the taunting claim that “Faith is belief without evidence.” The earliest source for this I can find is from the American journalist Ambrose Bierce, who defined “faith” in his satirical book The Devil’s Dictionary (1906): “Faith, n. Belief without evidence in what is told by one who speaks without knowledge, of things without parallel.”

Richard Dawkins, the scientist, author, and atheist activist, has repeated many variations of “faith is belief without evidence” in much of his writing. Indeed, it’s hard to get through a discussion of religion on social media without somebody posting “Faith [by which they mean religion] is belief without evidence,” as if this settles some argument.

The “faith is belief without evidence” claim is saying that religion itself is nothing but claim of knowledge that cannot be empirically proven. Certainly parts of contemporary religion have devolved into little more than a superstitious belief system. But as I wrote in the last post, in most of religion’s history merely believing things, even things about God, wouldn’t have qualified as religion at all.

Religion Is Not About Belief

The author and religious scholar Karen Armstrong has argued many times in her prolific writing that religion is not about belief. Until the modern period, even the monotheistic traditions were primarily about practice, she says. Jews observed the Sabbath and followed the Law. Christians participated in sacraments (e.g., communion, baptism) and practiced charity. Muslims practiced the Five Pillars. And much of this is still true.

Armstrong wrote in her book The Case for God (2009),

Religion as defined by the great sages of India, China, and the Middle East was not a notional activity but a practical one; it did not require belief in a set of doctrines but rather hard, disciplined work, without which any religious teaching remained opaque and incredible.

You might argue that there are beliefs supporting these practices — that there is a God, for example — and you would be right. But the beliefs were less important than the actions, the observances. The practioner might have only the vaguest notion of who or what “God” is but followed tradition practices wholeheartedly, and that was what it was to be “religious.” See also a note from Carl Jung on the psychological importance of ritual in religion.

The Meaning of Faith

The word faith is from the Latin fides and the Old French feid, which primarily meant faithfulness, trust, loyalty, honesty, truthfulness. The sense of faith as belief, as accepting a teaching or proposition as true without relying on evidence, is only a small part of what it means even in a religious context. For that matter, the word belief evolved from an Old German word that meant one cared about something and held it in esteem. To believe in the sense of accepting the truth of a proposition dates to the 16th century or so.

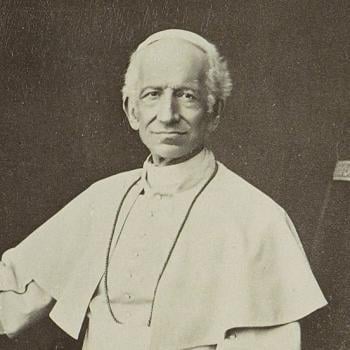

The great theologians of history said a great deal about faith, but none of them I could find described faith as simply accepting doctrines as truth without question. Augustine (354-450), for example, wrote that faith must not contradict what reason says is true, although faith may certainly speak where reason is silent. Scholarly treatises on faith and theology mostly describe religious faith as trust combined with commitment. For a monotheist, faith in the traditional sense would be an orientation toward God even if God is something beyond understanding.

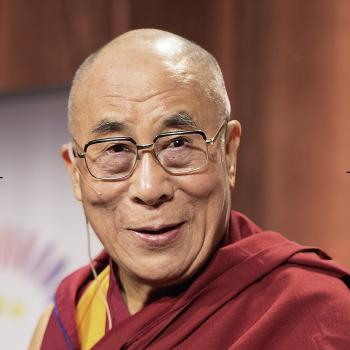

Faith in other traditions is not dissimilar. The Sanksrit word sraddha (in Pali, saddha) is often translated into English as “faith,” but it can also mean trust, confidence, or fidelity. The Theravadin monk and scholar Bikkhu Bodhi said: “As a factor of the Buddhist path, faith (saddha) does not mean blind belief but a willingness to accept on trust certain propositions that we cannot, at our present stage of development, personally verify for ourselves.” Buddhism is very much about personally testing and verifying teachings rather than just accepting what one is told. Yet faith is still part of Buddhism.

Dynamics of Faith

In his book Dynamics of Faith, Paul Tillich defined religious faith as “the state of being ultimately concerned.” He continued, “Faith as ultimate concern is an act of the total personality. It happens in the center of the personal life and includes all its elements. Faith is the most centered act of the human mind.”

As I understand Tillich, what he called faith might be described as affective or dispositional rather than cognitive. It is a turning toward the mystery of life. If we consider Joseph Campbell’s definition of God — “God is a metaphor for that which transcends all levels of intellectual thought. It’s as simple as that.” — then this kind of faith does not presume to know what God is, but is always open to God anyway. And if revelation comes, it comes.

On the other hand, Tillich wrote,

The most ordinary misinterpretation of faith is to consider it an act of knowledge that has a low degree of evidence. Something more or less probable or improbable is affirmed in spite of the insufficiency of its theoretical substantiation. This situation is very usual in daily life. If this is meant, one is speaking of belief rather than faith.

Faith Is Many Things

Religious faith may be propositional — faith in doctrines; faith in a particular idea of God — or not. And it may focus inward toward ideals or insight or outward toward, well, something thought to be out there.

There are people who can’t imagine any other sort of religious faith than believing in unseen and imaginary things, in the same way a child believes in Santa Claus. This is an infantile kind of faith, and it’s not what mature religious faith is about. A person of faith really can be as rational and logical as anyone. For those who are solidly stuck in the belief that “faith is belief without evidence,” however, I doubt anything one can say will change their minds.