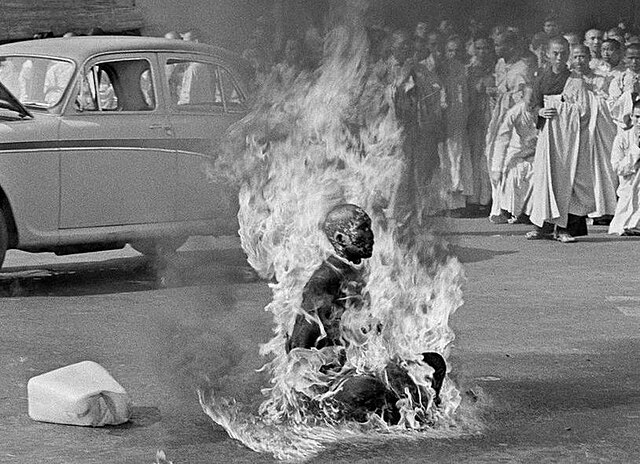

One of the most iconic images of the 20th century is the photograph of a Vietnamese Buddhist monk burning himself to death on the streets of Saigon. The monk was named Thích Quảng Duc, and he died of self-immolation on June 11, 1963 at about the age of 66. But why?

Self-immolation as a form of protest is in the news after a U.S. Air Force enlisted man livestreamed his self-immolation. He killed himself in front of the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C., to protest the war in Gaza. In recent discussion forums about this incident I’ve seen comments claiming Thích Quảng Duc self-immolated to “protest the war.” Sometimes it’s “to protest the American war,” although the large deployments of U.S. combat troops to Vietnam didn’t begin until 1965. In fact, Quảng Duc’s protest was not primarily, if at all, about the war, and in this post I want to explain why a Vietnamese Buddhist monk self-immolated in 1963.

I also want to concur with Graeme Wood, writing for The Atlantic, that As a Tactic, Self-Immolation Is Often Counterproductive. Thích Quảng Đức’s flaming suicide may have been the first time in history anyone self-immolated as a form of protest, but hundreds of people have done it since. And while Thích Quảng Duc’s sacrifice did produce some results, all those other hundreds of horrific deaths have not. For example, since 2009, 159 Tibetans have self-immolated in Tibet and China to protest Beijing’s policies toward Tibetan Buddhism, and nothing has changed. At worst, self-immolations have been used to discredit the cause of the protester. It’s nothing but a grisly publicity stunt. So let’s not glorify it or encourage it.

Thích Quảng Duc: Historical Background

In order to understand why Thích Quảng Duc self-immolated, we need a bit of historical background. In the 19th century the territory of Vietnam was absorbed into French Indochina, part of the colonial empire of France. French Indochina contained what is now Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. French rule of Vietnam introduced many Catholic missionaries into the country. Today about 6 percent of the population of Vietnam is Catholic. That percentage probably was higher during the colonial period but was never close to a majority. French rule also encouraged economic inequality. “Whatever economic progress Vietnam made under the French after 1900 benefited only the French and the small class of wealthy Vietnamese created by the colonial regime,” says Britannica.

Japanese troops occupied Vietnam, with the permission of Vichy France, begining in September 1940 and until the end of World War II in 1945, when Vietnam was officially returned to the control of France. During the Japanese occupation a group called the Viet Minh, or Vietnamese Independence League, was formed in opposition to both French and Japanese control of Vietnam. The Viet Minh fought back against the Japanese, and by the end of World War II they controlled most of north and central Vietnam. Immediately after the Japanese surrender and before Allied troops could arrive, the Viet Minh took control of the government of Vietnam. On September 2, 1945, the Viet Minh leader Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam’s independence from France. This led to the First Indochina War, between the Viet Minh and France. Sidestepping a long and extremely messy story and getting right to the result, in 1954 Vietnam was partitioned into North and South Vietnam. North Vietnam had a Communist government headed by Ho Chi Minh. A man named Ngô Đình Diệm (1901-1963) was named Prime Minister of South Vietnam. France decided it was done being a colonial power in Asia and withdrew from Indochina.

This was not the end of fighting. Elections that were supposed to unite north and south never happened. North Vietnam began preparing for guerrilla war against Diem’s government by building a supply route through Laos and Cambodia that came to be called the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The United States, obsessed with stopping the “spread of Communism” in Asia, sent military advisors and other military aid to South Vietnam to prop up the Diem government. The Diem government, unfortunately, was corrupt and riddled with internal divisions.

Thích Quảng Duc: The Buddhist Crisis

Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm was from one of the elite families that had thrived in the colonial period. He was also Catholic and determined to use his position to promote Catholicism. His policies blatantly favored Catholicism over Buddhism, which had been practiced in Vietnam for 18 centuries. Catholics were favored for government positions and military promotions. It came to be assumed that Catholicism was a prerequisite for a successful career. Firearms distributed to villages for self-defense against guerrillas went to Catholics only. Catholics were exempt from conscripted labor; Buddhists were not. Some entire villages converted to Catholicism so they could receive government aid.

In May, 1963, matters came to a head when the government banned all public observance of Vesak, a significant Buddhist commemoration of the birth, enlightenment, and entry into final nirvana of the Buddha. Buddhists could not so much as fly a Buddhist flag in public. Officials cited an obscure law that prohibited religious flags, even though the Vatican flag was displayed all over Vietnam. On May 8, 1963, Buddhists in the central Vietnamese city of Hue — where Ngô Đình Diệm’s brother served as Catholic archbishop — gathered to listen to a radio address regarding Vesak. When the radio broadcast failed to play, the crowd grew restless. People took down a South Vietnamese flag and replaced it with a Buddhist flag. South Vietnamese police and soldiers arrived to “keep the peace.” They fired into the crowd, killing nine people, including children. Ngô Đình Diệm blamed the incident on Communist infiltrators.

This was the beginning of the “Buddhist Crisis.” Senior Buddhist monks made five demands: equality with Catholics, compensation for the victims’ famillies in Hue, freedom to fly the Buddhist flag, freedom from arbitrary arrests, and punishment for the officials responsible for the massacre at Hue. Talks between Buddhist clergy and the government achieved some small concessions, but not many. On May 30, more than 500 monks demonstrated in front of the National Assembly in Saigon. After four hours they returned to their pagodas to begin a hunger strike. The government made more small concessions, but civil unrest continued. On June 3, a day of demonstrations in several cities, police and soldiers in Hue poured acid on the heads of demonstrators who were praying in front of a Buddhist pagoda, or shrine. Many people had to be hospitalized. Unproductive talks between Buddhist clergy and the government continued.

The Self-Immolation of Thích Quảng Duc

So it was that on June 11, 1963, about 350 Buddhist monks and nuns walked behind a car from a nearby pogoda to an intersection in Saigon near the Cambodian Embassy. At the intersection, Thích Quảng Duc and two other monks got out of the car. One monk put a meditation pillow on the road while another took a five-gallon gan of gasoline out of the trunk. Thích Quảng Duc sat on the pillow; the contents of the gasoline can were poured over him. The monks and nuns made a circle around him. He chanted to Amitabha Buddha — Nam mô A Di Đà Phật — and struck a match.

The press had been notified that something significant would happen at the intersection that day, but few bothered to come. Among those who did was Malcolm Browne of the Associated Press, whose photographs taken that day were seen around the world. Another was David Halberstam, who would go on to be a best-selling author of several books. “I was too shocked to cry, too confused to take notes or ask questions, too bewildered to even think,” Halberstam wrote later. Witnesses all said that the monk was still and silent through the whole ordeal. After about ten minutes the body collapsed. The still-smokng corpse was wrapped in a yellow rope and placed in a coffin, and then it was carried to Xá Lợi Pagoda in central Saigon. Outside the pagoda, banners were hung proclaiming that a Buddhist monk had burned himself “for our five requests.”

I have read since then that five more monks self-immolated in Vietnam in 1963, after Thích Quảng Đức, but these sacrifices got little media attention.

Immediate Consequences

Although I was only about 12 years old at the time, I remember the photographs of the burning monk. I didn’t understand the reason. I’m not sure how much most Americans understood the reason. Vietnam was in the news a lot in those days. The wife of Ngô Đình Diệm’s younger brother and chief adviser, Ngô Đình Nhu, was always saying outrageous things and getting in the news magazines. Madame Nhu, as she was called, scoffed at the “monk barbeque show.” The Diệm government claimed the monk had been drugged and forced to kill himself. They also accused Malcom Brown of somehow bribing the monk to take his life to get his photograph.

President John Kennedy was running out of patience with the whole Diệm regime. The South Vietnamese Army kept losing in spite of superior numbers and munitions. And the American public was not fond of the Diệm family, including the mouthy Madame Nhu. President Kennedy advised Prime Minister Diệm that he needed to take the Buddhist crisis more seriously and also clean up his government, and fast. Instead, in August, Diệm declared martial law and sent troops to raid the pagodas of the Buddhist group behind the protests.

Shortly after the raid, some South Vietnames military officers contacted the U.S. government to inquire how the U.S. might respond to a coup overthrowing Diệm. After much discussion, the U.S. responded with their concerns and conditions, but more or less said, “go ahead,” as long as Ngô Đình Nhu was overthrown also. On November 2, 1963, Diệm and Nhu were assassinated while Madame Nhu was in California. She was an exile the rest of her life.

From Then On

President Kennedy was assasinated in Dallas on November 22, 1963. He was succeeded by his vice president, Lyndon Johnson, who made the decision in 1965 to send U.S. combat troops into Vietnam. You might remember that did not go well. The end result was that U.S. troops were withdrawn, to much public relief in the U.S., in 1973. In 1975 North Vietnamese troops gained control of the entire country. North and South Vietnam were united as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

It would be nice to think the Buddhists of Vietnam achieved religious freedom after Thích Quảng Đức’s sacrifice, but they did not. Like other Communist governments, the Vietnamese Communist Party doesn’t trust anything it can’t control. After unification two Buddhist organizations formed in Vietnam—the government-sanctioned Buddhist Church of Vietnam (BCV) and the independent Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBCV). The UBCV refused to join the BCV. Many of its senior clergy were imprisoned, some for many years, and its temples raided and seized. Even so, the government is fine with the veneration of Thích Quảng Duc.