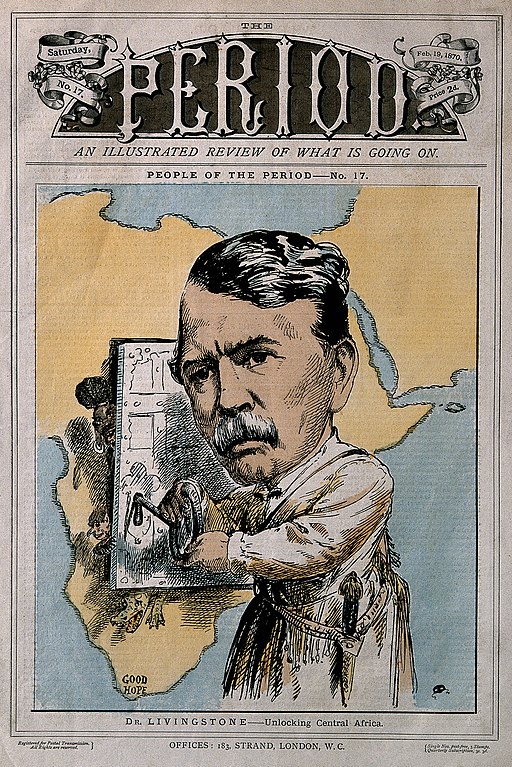

“Dr. Livingstone, I presume.” The famous encounter between journalist Henry Morton Stanley and missionary David Livingstone in 1871 is the stuff of legend. It’s also the stuff of at least a couple of films (Stanley and Livingstone, 1939, starring Spencer Tracy as Stanley; and Forbidden Territory: Stanley’s Search for Livingstone, 1997, starring Aidan Quinn as Stanley and Nigel Hawthorne as Livingstone). And it was the stuff of a Muppets skit starring Bert and Ernie. And a 1968 pop song by the Moody Blues. And a library full of books. And after all this there is some question whether Stanley really said “Dr. Livingstone, I presume,” on meeting Livingstone. We don’t really know. It still makes a great story. But why was this meeting such a big deal?

In the late 19th century, David Livingstone (1813-1873) was one of the most famous people in the western world. He was a Congregationalist missionary and physician admired for his pioneering work in Africa. His writing and lectures are credited with helping to end the East African Arab–Swahili slave trade, a notable accomplishment. In 1866 he returned to Africa on a quest to find the source of the Nile. In the course of this quest he lost contact with the outside world. For six years his admirers around the world didn’t know if he was living or dead.

The New York Herald sent its correspondent Henry Stanley (1841-1904) to Africa to find Livingstone. And a legend was born that inspired books and films and songs and a Muppets skit more than a century later.

Dr. Livingstone, I Presume: About David Livingstone

The driving force of David Livingstone’s early life was the reconciliation of his two loves, Christianity and science. He was born into a working class family in Blantyre, Scotland, and began working in a cotton mill at the age of ten. His father Neil taught Sunday School and liked to hand out Christian tracts while engaged in his job as a door-to-door tea salesman. Neil Livingstone read books on theology and Christian missionary work, and this rubbed off on David. But David also developed a deep interest in natural science. As a youth Livingstone was influenced by the work of the Rev. Thomas Dick (1774-1857), a minister and astronomer who wrote about reconciling Christianity and science.

Young Livingstone also admired the Rev. Ralph Wardlaw (1779-1853), a Scottish Congregationalist minister who is remembered for his work to abolish slavery. Livingstone had been raised in the Church of Scotland, which taught a doctrine of predestination. This states that only some people are predestined to receive salvation. But he came to prefer the idea that salvation is open to everyone who sincerely seeks it. At the age of 15 Livingstone left the Church of Scotland to join a Congregationalist church.

A Call to Mission Work

When David Livingstone was 21 his father gave him a pamphlet calling for missionaries trained as doctors to go to China. Thus Livingstone was inspired to become a physician-missionary. He attended the Andersonian Institute — now the University of Strathclyde — in Glasgow, where he studied medicine and chemistry. And in Glasgow he was able to attend theology lectures by the Ren. Ralph Wardlaw at the Congregational Church College. He paid for his education by working part of the year at the mill back home in Blantyre. He was nothing if not persistent.

Once he finished his medical studies in Scotland, Livingstone applied to the London Missionary Society. Accepted on probation — he was judged to be a bit “rustic” — he studied to become a Congregationalist minister while continuing to learn medical skills at Charing Cross Hospital Medical School. In 1840 he became both a licensed physician and an ordained minister. In November 1840 he left Britain, bound for the Cape of Good Hope.

Livingstone the Missionary

In his first few years in South Africa, Livingstone worked with missionaries who had already established mission stations. Among these was the Moffat family, who had established a mission station near a village called Mambotsa. While there Livingstone attempted to protect some sheep from a lion and instead was attacked by a lion. He survived, but with a broken arm. The daughter of the Moffat family, Mary, took care of Livingstone as he recuperated. David Livingstone and Mary Moffat married in January, 1845. In spite of the fact that David spent most of their marriage off exploring somewhere, the couple managed to produce six children.

As Livingstone moved on to other missions, it has to be admitted that he had little success bringing anyone to Christianity. It appears his real passion was exploring. He and another expat Brit, William Cotton Oswell (1818-1893), in 1849 crossed the Kalahari Desert and reached Lake Ngami, which earned him the recognition of the Royal Geographic Society. The pair also explored the Zambezi River, the fourth largest river in Africa. Livingstone was the first European to see the great falls of Mosi-oa-Tunya on the Zambezi, which Livingstone renamed Victoria Falls. Livingstone was now famous as the first European to cross south-central Africa at that latitude.

Along the way Livingstone appears to have developed a genuine fondness, and respect, for Africans. He also had a Victorian-era faith in the benefits of British civilization, free commerce, and Christianity, and he wished to bring those things to Africans. His motto became “Christianity, Commerce and Civilization.” More than anything else he wanted to abolish the African slave trade, and he believed developing Africa for other types of commerce and trade would make that possible.

Later Adventures

Livingstone returned to London in 1856 and was celebrated as a national hero. He was mobbed by fans and showered with awards. And he was in great demand as a speaker. He turned his journals into a book titled Missionary Travels, which became a best seller. He remained eager to return to Africa and explore routes for commercial trade, which he believed was key to ending the slave trade. The London Missionary Society, however, reminded him his primary task was spreading the Gospel of Jesus.

Livingstone resigned from the LMS in 1857 and was appointed Her Majesty’s Counsel to parts of Africa. The Foreign Office arranged for him to lead an expedition into the lands of Zambezi River and Lake Malawi. This expedition turned out badly. Livingstone possibly was not meant to be a leader of anything. Most of the party eventually bailed on the project. Livingstone’s wife Mary died of malaria along the way in 1862; she was buried in Mozambique. He returned to London in 1864 with his reputation tarnished. Still, the Royal Geographical Society and many friends supported him. They were willing to sponsor his next adventure, to find the source of the Nile. Livingstone left London on his final expendition in 1865. He planned to return in two years.

David Livingstone was known to have entered Africa in 1866 at the mouth of the Ruvuma River on Africa’s eastern coast, roughly on the border between Tanzania and Mozambique. And then he disappeared. Occasional reports of alleged Livingstone sightings were printed in western newspapers, but no one outside Africa knew if he was alive or dead. It was later learned that soon after the expedition began much of Livingstone’s equipment was stolen, and his porters deserted him. Tropical diseases sapped his strength. At one point he had no other option but to travel with slave traders. At last he found shelter in Nyangwe, a village on Lualaba River in what is now the Republic of the Congo, and remained there.

Dr. Livingstone, I Presume: Henry Stanley’s Journey

James Gordon Bennett Jr. was the editor of the New York Herald, a widely read, sensationalist newspaper founded by Bennett’s father in 1845. In October 1869 Bennett Jr. saw an opportunity in the mystery of what happened to David Livingstone. He ordered one of his new correspondents, Henry Morton Stanley, to either find the explorer or “bring back all possible proofs of his being dead.” Stanley was a Welsh-born writer and adventurer who had immigrated to the U.S. when he was 18. Organizing an expedition took some time, but early in 1871 Stanley left from the east coast of Africa to begin the journey inland to find Livingstone.

Over the next three months Stanley suffered malaria, dysentery, and starvation. He lost 40 pounds. Two other White men with him died, one of elephantiasis and the other of smallpox. Most of the porters either deserted or died. In June he arrived in Tabora, a village on the savanna that offered some comforts of civilization. From there he was able to write a 5,000-word dispatch for the Herald, the first of the expedition. Stanley ended his dispatch with the rumor of a White man living in a village called Ujiji in in the British territory of Tanganyika. A caravan going east gave the dispatch to the American consul in Zanzibar, who sent it to New York by ship. It would fill the front page of an edition of the Herald.

Stanley did believe Livingstone might be in Ujiji, but the road from Tabora to Ujiji was blocked by a tribal war. In the meantime, Stanley was suffering hallucinations, a symptom of severe cerebral malaria. How could the mission succeed?

Meanwhile, Back in Nyangwe

Livingstone had come to enjoy watching the marketplace in Nyangwe from a comfortable chair. One day in July, 1871, some Arab slave traders came and began to quarrel with the villagers. Suddenly the slavers began to fire guns into the crowd. “Men opened fire on the mass of people near the upper end of the marketplace, volleys were discharged from a party down near the creek on the panic-stricken women who dashed at the canoes,” Livingstone wrote in his journal. About 400 Africans were massacred. After the massacre Livingstone fled Nyangwe for Ujiji, about 240 miles (390 km) away. His shoes fell apart; he developed dysentery. He arrived in Ujiji in October, starvng and weak.

Meanwhile, Stanley had left Tabora to find a safer, round-about way to Ujiji. As with the first part of the journey, all suffered sickness and food shortages. A favorite donkey was killed and eaten by crocodiles in the Malagarasi River. The expedition pushed on. And eventually the Herald expedition entered Ujiji with U.S. flags flying. Livingstone, sitting on a straw mat in front of the little house where he had been staying, heard the commotion. He got up to see what was going on.

The hour had come. Stanley wrote later that he removed his pith helmet and held out his hand to the frail, old White man who approached him. “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” Stanley said.

“Yes,” said David Livingstone.

Dr. Livingstone, I Presume: Postscript

Stanley had entered the date of the famous meeting in his journal as November 10, 1871, but it’s believed he had lost track of time and the real date was October 27. The two men bonded quickly and explored Lake Tanganyika together. Stanley wanted to take Livingstone to London, but Livingstone had not given up on finding the source of the Nile. He was nothing if not persistent. Eventually they both went back to Tabora, where Livingstone was furnished with new equipment and new porters. They parted on March 14, 1872, when Stanley left for Zansibar. And the New York Herald had one of the greatest scoops of the ages when it reported, on May 2, 1872, that Livingstone had been found. The news made headlines around the world.

Livingstone never did find the source of the Nile. He died of disease in what is now Zambia on May 1, 1873. His mummified remains were buried in Westminster Abbey on April 18, 1874. Henry Stanley was one of the pallbearers. Stanley later made another trip to Africa, also to look for the source of the Nile, but he didn’t find it, either.

As time went on many questioned David Livingstone’s commitment to missionary work. He may not have been successful at mission work, but his Christian faith seems to have been sincere. He wrote in his journal, “I place no value on anything I have or may possess, except in relation to the kingdom of Christ. If anything will advance the interests of the kingdom, it shall be given away or kept, only as by giving or keeping it I shall promote the glory of Him to whom I owe all my hopes in time and eternity.”