President Abraham Lincoln made Thanksgiving a U.S. national holiday for the first time in 1863. This was at the height of the American Civil War, which began in April 1861 and ended in April 1865. It may seem odd that Thanksgiving had suddenly become important in such a tragic time. But President Lincoln had reasons to be thankful.

Through 1861 and 1862 the Union lost more battles than it won, and what victories it could claim came at a shocking loss of life. The first half of 1863 didn’t go well for the Union, either. In particular, the Confederate victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville (April 30-May 6, 1863) was another massive setback for the Union. But in July the war reached a turning point. Union troops under the command of Maj. Gen. George Meade decisively won the Battle of Gettysburg on July 3. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee had invaded Pennsylvania in hopes that winning a battle in a northern state would force the Union to negotiate a peace. Instead, Lee’s much weakened army was forced to retreat back to Virginia to keep fighting.

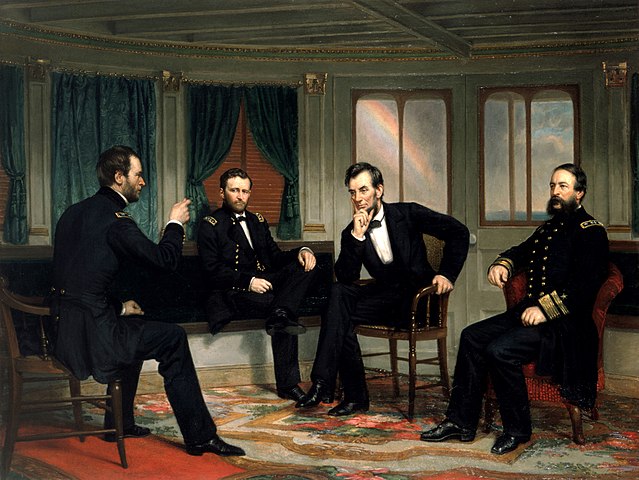

And on July 4, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant accepted the surrender of Confederate forces in Vicksburg, Mississippi after a dogged campaign of several months. Although Gettysburg gets more attention, the victory at Vicksburg probably pleased President Lincoln even more. It brought the entire Mississippi River under Union control and cut the Confederacy into two divided territories. Lincoln had followed the progress of Grant’s campaign closely and called it “the most brilliant in the world.” Earlier Lincoln had said, “Vicksburg is the key! The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.” And now he had the key.

The Thanksgiving Crusade of Sarah Josepha Hale

There was another factor in Lincoln’s decision to make Thanksgiving a holiday: Sarah Josepha Hale. From 1837 to 1877, Hale was the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, a hugely popular monthly magazine for women. Before the Civil War, Godey’s was the most widely circulated magazine in the U.S. And Hale was a genuine influencer of her time. She used the magazine to advocate for various causes, such as higher education and professional employment for women.

Hale also advocated for making Thanksgiving a national holiday. For a time Thanksgiving was mostly a New England tradition with no agreed-upon date. President George Washington had declared a day of “public thanksgiving and prayer” in 1789, and presidents Adams and Madison followed suit, but then the practice was dropped. And these early obserances were more about prayer and reflection than dinner. There was little remembrance of the now-celebrated 1621 Prilrim harvest feast shared with indigenous Wampanoag neighbors until an account of it was published in a popular book in 1841. Hale thought a nationally celebrated Thanksgiving, complete with feasts, would be just the thing to heal the nation’s increasing partison rancor over the issue of slavery.

And so Hale promoted Thanksgiving in every November edition of Godey’s Lady’s Book. She published recipes for the dishes we now think of as “traditional” for Thanksgiving — roasted turkeys with savory stuffing, cranberry sauce, pumpkin pies. In truth, none of these dishes were served at the original Pilgrim Thanksgiving feast of 1621. But in Hale’s time they reflected popular Victorian-era notions of what a “fancy” dinner should include. Stuffed turkeys and pumpkin pies became inextricably linked to Thanksgiving because of Hale. Hale also wrote to a succession of presidents asking them to declaree a national Thanksging holiday. And in 1863, President Lincoln decided Thanksgiving was what the nation needed.

Abraham Lincoln’s Thanksgiving Proclamation

Abraham Lincoln’s Thanksgiving proclamation of 1863, issued on October 3, begins:

The year that is drawing toward its close has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary a nature that they cannot fail to penetrate and even soften the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever-watchful providence of Almighty God.

In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity, which has sometimes seemed to foreign states to invite and provoke their aggressions, peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere, except in the theater of military conflict; while that theater has been greatly contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union.

Lincoln set the date of the holiday for the last Thursday in November, which in 1863 fell on November 26. Many Union troops enjoyed Thanksgiving dinners, often supplied by civilian organizations such as the U.S. Sanitary Commission. The Sanitary Commission was organized to, among other things, provide medical supplies, food, and clothing to troops as needed. Depending on where they were deployed, some troops enjoyed a real Thanksgiving dinner. One soldier’s letter tells us the Sanitary Commission brought them a dinner of roast turkey, chicken, and apples. Others probably did without. Gen. Grant’s troops in Tennessee had just won the Battle of Missionary Ridge in Chattanooga on November 25 and may have been out of the reach of the Sanitary Commission.

Abraham Lincoln’s Thanksgiving: Postscript

Thanksgiving has remained an annual national holiday in the U.S. ever since, held on the last Thursday in November. Well, nearly always. In 1939 the last Thursday in November fell on the last day in November, and merchants worried that the Christmas shopping season would be too short. President Franklin Roosevelt changed Thanksgiving to the next-to-last Thursday in November. This continued through 1940 and 1941. But the date change caused so much chaos and confusion that in December 1941 Congress passed a law that permanently fixed the holiday to the fourth Thursday in November.