China’s claim to Tibet as a territory of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is an ongoing controversy. According to China, the invasion of Tibet by PRC troops in 1950 was not an invasion but a liberation. China and Tibet have been one nation since the 13th century, according to China. As you might have heard, Tibetans tend to see things differently.

A large part of China’s claim to Tibet involves the lineage of Dalai Lamas. The last post, on the Sixth Dalai Lama’s Short and Tragic Life, ended with a cliffhanger: The young Sixth Dalai Lama was kidnapped and killed by a Mongol warlord named Lajang Khan (also spelled Lha-bzang), who then claimed the title King of Tibet. What would the Tibetans do? What would happen next?

What happened next was a series of events that ended with Lajang Khan deposed and the Seventh Dalai Lama, Kelzang Gyatso (1708–1757) enthroned in Potala Palace. However, this outcome required the intervention of the Kanxi emperor of China (1654–1722; sometimes spelled Kangxi), third emperor of the Qing Dynasty. The intervention established a complex relationship between Tibet and the Qing Dynasty (1636–1912), which ended with the establishment of the Republic of China. In 1913 the Thirteenth Dalai Lama issued a proclamation declaring that with the end of imperial China, Tibet’s relationship with China was dissolved “like a rainbow in the sky.” That relationship was between Tibetan Buddhism and China’s emperors, not the nation of China, and it did not carry over to the new Republic of China, he said. And that’s where matters stood until 1950, when China invaded Tibet.

China’s Claim to Tibet: The Earlier Story

China’s claim to Tibet rests on a version of history that begins in 1271, when the Mongol ruler Kublai Khan (1215–1294) became emperor of China, founding the Yuan Dynasty. The PRC argues today that Kublai Khan also ruled Tibet, effectively merging Tibet and China. Kublai Khan’s relationship with Tibet involved a patron-priest relationship with a high lama of the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism, but beyond that historians disagree over whether the Great Khan “ruled” Tibet, exactly. It’s complicated. Kublai Khan did rule much of the Korean peninsula, Siberia, Afghanistan, and some other places China doesn’t claim today. Further, after the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) came the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), and the Ming emperors made no claims to Tibet or attempt to rule it.

The Fifth Dalai Lama (1617–1682) was the first Dalai Lama to rule Tibet (see “How the Fifth Dalai Lama Became Ruler of Tibet“). The Great Fifth established diplomatic relations with the Qing Dynasty. He traveled to Beijing, arriving in 1654, at the invitation of the Shunzhi emperor (1638–1661). Most accounts of this visit describe the Shunzhi emperor giving the Great Fifth the honors of a visiting head of state and an important ally of China. However. today the PRC describes it as marking the submission of the Dalai Lama’s government to China. Similar claims are made today regarding the relationship of the Panchen Lama, the second highest lama of Tibet, to the Qing court.

The End of Lajang Khan

Now let’s pick up the story where the last post ended. The Sixth Dalai Lama died in 1706 while in the custody of his Mongolian kidnappers.. Lajang had planned to take the Dalai Lama to Beijing, at the request of the Kanxi emperor, but the entourage was still traveling east on the Tibetan Plateau when the Dalai Lama died. Lajang returned to Lhasa to rule as King of Tibet. He attempted to install another young monk as the “true” Sixth Dalai Lama, but the Tibetans did not accept him. Meanwhile, word got around that a Seventh Dalai Lama had been born and identified in Litang, a Himalayan community roughly 900 miles (1448 km) east of Lhasa. At the time, this was considered eastern Tibet. Lajang Khan sent men to Litang to kill the boy. But his father moved him to the Kingdom of Derge, where he was protected by Tibetan and Mongol soldiers who were loyal to the Dalai Lama.

Meanwhile, the heads of the largest Gelugpa monasteries — Drepung, Sera, and Ganden — plotted against Lajang Khan. The abbots found an ally in the leader of another Mongol tribe, the Junghars (also spelled Dzungars). The Junghar army reached Lhasa in 1717. After two months of fighting the Junghars resorted to stealth. One night Tibetans dropped ladders down the fortified walls for the Junghars to climb. The Junghars finally were inside Lhasa, taking Lajang’s troops by surprise. Lajang Khan fled Lhasa with three companions, but Junghar pursuers caught up to him and killed him. The “alternate” Dalai Lama was deposed as well.

Tibet was freed of Lajang Khan, but soon Tibetans realized they had a bigger problem — the Junghars. They were lawless and destructive. They subjected Tibetans to atrocities and were especially violent toward temples and monks of the Nyingma school of Buddhism. And the Seventh Dalai Lama was still far away.

The Emperor of China Intervenes

While the Junghars were still outside his gates, Lajang Khan had sent a letter to the Kanxi emperor in Beijing asking for his help. The emperor organized his troops and began the long march to Tibet. Then the emperor learned the situation had changed, and he would need to invade central Tibet and drive away the Junghars. He also reached out to the family of the Seventh Dalai Lama, then 12 years old, and promised to escort the boy safely to Lhasa and see him enthroned in Potala Palace as the rightful Dalai Lama. By the time the Chinese army reached Tibet, the Junghar occupation had degenerated into roaming bands of thugs and bandits. The Chinese troops soon restored order to Tibet, and the surviving Junghars were banished.

In 1720 the Seventh Dalai Lama entered Lhasa at the head of a great procession. The people of Lhasa were ecstatic and grateful to the Kanji emperor and his army. The Kanji emperor took advantage of this opportunity to remake Tibet. As part of this he claimed a large part of eastern Tibet, merging former Tibetan territory into the Chinese provinces of Qinghai and Sichuan. The exhausted Tibetans did not object. The emperor also installed a garrison of Chinese troops in Lhasa (although the garrison was recalled by his heir, the Yongzheng emperor, shortly after the Kanxi emperor died in 1722). And he established a council of three Tibetan officials to govern Tibet. The Dalai Lama’s role was to be strictly religious.

This began a complicated relationship between Tibet and the Qing Dynasty. There is no question the Qing emperors had considerable influence over the government of Tibet. Subsequent emperors also sent armies to Tibet to protect it from invaders or quell insurrection. Qing emperors installed representatives, called “ambans,” in Lhasa to report back to Beijing. The ambans also often influenced Tibetan government decisions in ways that benefited China. But did this relationship make Tibet part of the nation of China? Or did it make Tibet a satellite of Qing Dynasty influence that Qing protected out of its own interests? Granted, this is only the beginning of a complicated story. The terms of the relationship between Tibet and China shifted quite a bit over the years.

Next: Insurrections

The council established by the Kanxi emperor to govern Tibet did not last long. The three officials, from three different noble families, did not work together harmoniously. Peak dysfunction was reached in 1727, when two of the officials assassinated the third. This brought about a civil war in Tibet. A respected landowner and military man named Polhane Sonam Topgye (1689–1747) organized an army to restore order. Pholhane’s troops were joined by troops sent from China by the Yongzheng emperor. The result of all this was that Pholhane became de facto king of Tibet. To this day Pholhane is regarded as one of Tibet’s wisest and best rulers.

Although the Seventh Dalai Lama had taken no part in the uprising (although his father probably did), the Yongzheng emperor wanted him removed from Lhasa. He was too compelling a symbol for rebels to rally around. The Seventh Dalai Lama was sent away to eastern Tibet. After the Chinese troops had left, Pholhane brought the Seventh Dalai Lama — but not his father — back to Lhasa to restore normal order. The Seventh Dalai Lama’s authority was restricted to religious matters exclusively, however.

When Pholhane died in 1747 he was succeeded by his son, Gyurme Namgyal. The son was nothing like his father and made a series of unwise decisions that drew the attention of a new Qing emperor, Qianlong. In 1750 the Qianlong emperor had his ambans in Lhasa assassinate Gyurme Namgyal. This stirred up another insurrection. Tibetans had not liked Gyurme Namgyal, but at least he was Tibetan. The emperor’s ambans were Manchu. A mob set the ambans’ residence on fire and killed them. So once again the emperor of China sent troops to Tibet. Order was restored.

The Dalai Lama Restored to Power, Briefly

“The emperor was minded to appoint new ambans to head the Tibetan government, a move that would have transformed Tibet into a colony of China,” writes Sam van Schaik in Tibet: A History (Yale University Press, 2011). “But he saw that this would be difficult to achieve and would only infuriate the Tibetans, so it was decided instead to let the Dalai Lama resume his old role as the head of the Tibetan government.” Finally, at the age of 43, the Seventh Dalai Lama became the political head of Tibet. By all accounts he did a good job. He would be gone just seven years after the death of Gyurme Namgyal, however.

Through the remainder of the 18th century and most of the 19th, Tibet was governed by regents of the Dalai Lama and by a council called the Kashag. The Eighth Dalai Lama, it is said, preferred to let others run the government. The Ninth, Tenth, Eleventh, and Twelfth Dalai Lamas didn’t live long enough to assume a political role. It’s believed some or all of these four may have been assassinated, probably by their regents. After the brief tenure of the Seventh, a Dalai Lama would not function as head of state until the Thirteenth (1876–1933).

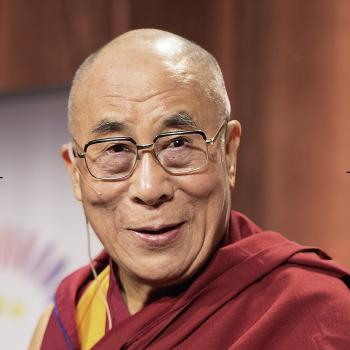

The relationship between China and Tibet continued to evolve, and some significant events took place during the time of the Eighth Dalai Lama that will affect what will happen when the current Dalai Lama, the Fourteenth, passes away. The government of the People’s Republic of China has already assumed the authority to recognize and enthrone the Fifteenth Dalai Lama. That claim is based in part on events that happened during the life of the Eighth Dalai Lama, Jamphel Gyatso (1758–1804). I will write about that in a future post.