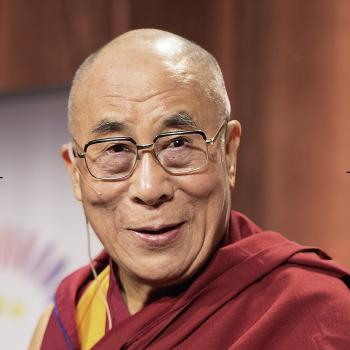

The government of China is in possession of a particular golden urn. This urn, it is alleged, is essential to choosing the tulku, or rebirth, of a Dalai Lama. You may be hearing a lot about the urn within the next few years. The Fourteenth Dalai Lama, His Holiness Tenzin Gyatso, is 87 years old. With all sincere wishes for his good health and long life, it must be acknowledged that he doesn’t have a lot of years left. And the government of China will very likely choose someone they can call the Fifteenth Dalai Lama after he’s gone.

In 2007 China’s State Administration of Religious Affairs released Order No. 5, which covers “the management measures for the reincarnation of living Buddhas in Tibetan Buddhism.” The order provides “application and approval procedures” for the proper reincarnations of “living Buddhas,” which is what the Chinese call Tibetan lamas. Applicants for reincarnation must apply to various parts of the bureaucracy of the People’s Republic of China to be approved and recognized. In short, a lama needs a permit to reincarnate. As ridiculous as this may sound to us, Beijing is deadly serious about this. Its aim is to be sure all religious authority within Tibetan Buddhism is under government control.

The Golden Urn in Chinese Regulations

Here is what Order No. 5 says about the golden urn.

Living Buddhas which have historically been recognized by drawing lots from the golden urn shall have their reincarnating soul children recognized by drawing lots from the golden urn.

Requests not to use drawing lots from the golden urn shall be reported by the provincial or autonomous regional people’s government religious affairs departments to the State Administration of Religious Affairs for approval; cases with a particularly large impact shall be reported to the State Council for approval.

The next question is, where did the golden urn come from, and is it really part of the traditional process of choosing rebirths of high Tibetan lamas? The answer to the second question is “not really.” This is clarified in the answer to the first question, the history of the golden urn.

Before the Golden Urn

The golden urn story begins during the time of the Eighth Dalai Lama, His Holiness Jamphel Gyatso (1758–1804). By all accounts the Eighth Dalai Lama was a quiet and studious fellow who preferred to leave political matters to his regent, and he doesn’t directly impact this story. Instead, we start with the Sixth Panchen Lama, His Holiness Lobsang Palden Yeshe (1738–1780). The Panchen Lama is the second highest lama in Tibetan Buddhism. The Sixth Panchen Lama traveled to Beijing in 1779–1780 at the request of the Qianlong Emperor (1711 – 1799; note that the Qianlong Emperor played a part in the previous post, China’s Claim to Tibet and the Seventh Dalai Lama). The Qianlong Emperor had a sincere interest in Tibetan Buddhism and treated his guest to the highest honors of a visiting dignitary. But while in Beijing the Panchen Lama contracted smallpox, and he died.

One of the Panchen Lama’s brothers, who also was a reborn lama called the Trungpa tulku, accompanied the Panchen Lama’s body back to Tibet. He also carried many precious gifts the Qianlong Emperor had given the Panchen Lama. On returning to Tibet, the treasure was deposited in the Tashi Lhunpo monastery, the traditional home of the Panchen Lamas.

The Sixth Panchen Lama had another brother who had been recognized as a reborn lama, the Shamar tulku, also called the Shamarpa. On hearing of this treasure, the Shamar tulku argued that the Qianlong Emperor’s gifts were personal gifts to the late Panchen Lama. Therefore, he argued, they belonged to the family, not to a temple. And the Shamar tulku demanded his share. The Trungpa tulku refused to allow any of the gifts to leave Tashi Lhunpo. So the Shamar tulku rallied monks from his own monastery, who then stormed Tashi Lhunpo and made off with a large part of the Qianlong Emperor’s presents.

The Sharma Tulku and the Gurkhas

The authorities in Lhasa were not pleased. The stolen treasure was taken from the Shamar tulku and returned to Tashi Lhunpo. The Shamar tulku was placed under house arrest in his monastery. But he escaped and fled to Nepal. Nepal had recently been conquered by Gurkhas, a people known for being fierce warriors. The Gurkha rulers of Nepal already were at odds with the government of Tibet over a controversy involving currency. The Gurkhas sent a letter to the Kashag, the primary governing council of Tibet, saying the Sharmar tulku would be held hostage until the Kashag agreed to their currency demands. The Kashag made a small concession but also said the Gurkhas were welcome to keep the Shamar tulku.

By then the Shamar tulku had given his allegiance to the Gurkhas and enlisted them on his side of the treasure dispute. A Gurkha army stormed into Tibet in 1788 and marched toward Tashi Lhunpo, pillaging and looting along the way. The Tibetan army was outmatched. The Qianlong Emperor’s agents in Lhasa sent word to Beijing of what was happening. The Qianlong Emperor sent an army to the border but encouraged the Tibetans to make a deal with the Gurkhas. The Shamar tulku acted as middleman.

The deal that was struck included a provision that Tibet pay an annual tribute to Nepal. Tibet made a first payment but balked at the second. The Gurkhas invaded again, and once more they headed to Tashi Lhunpo. This time the Ghurkas overwhelmed the old monastery and seized the treasure.

The Sino-Nepalese War

The Tibetan army was able to cut the Gurkha supply lines. And then the Qianlong Emperor’s army arrived, a force of 17,000 soldiers (one source says 70,000 soldiers, but I’m going with 17,000) led by one of the Emperor’s best generals. The combined Tibetan and Chinese armies pushed the Gurkhas out of Tibet, and then the Chinese army continued pushing into Nepal. The Gurkhas surrendered just 20 miles from Kathmandu.

Under the terms of the surrender, both Nepal and Tibet agreed to accept the suzerainty of the Qing emperor. This agreement today is the strongest element of China’s claim to have “ruled” Tibet for centuries before the 1950 invasion. I don’t know if the Chinese have explained why they don’t claim Nepal as well. But in Tibet: A History (Yale University Press, 2011) author Sam van Schaik argues that the Qianlong Emperor “was not contemplating making ‘Tibet’ part of ‘China’: the idea of ‘China’ as a nation state had not yet come into being.” The Emperor was not interested in trying to “rule” Tibet, van Schaik continues, because attempting such rule would have been “hugely expensive and an administrative nightmare.” The Emperor primarily wanted to keep the peace at the furthest reaches of his empire, at minimum expense.

In return for accepting suzerainty, the Qing Dynasty would help defend Nepal and Tibet against external aggression. This arrangement would lapse in the 19th century. Loot stolen from Tibetans by the Gurkhas was gathered and returned to Tibet, with the exception of the presents given to the Sixth Panchen Lama. Those were returned to Beijing.

The Golden Urn

For good reason, the Qianlong Emperor blamed the war on the fight between the Shamar and Trungpa tulkus over a treasure. And the roots of that fight, frankly, could be found in the political corruption of the system of choosing reborn lamas. Many tulkus came from the same few wealthy families, in part to encourage patronage for temples from those families. The dominance of the nobility in Buddhist institutions also reinforced the feudalism that dominated Tibet.

And so the Qianlong Emperor demanded that from then on, tulkus would be chosen through a kind of lottery method instead of through various divinations. Candidates’ names were to be written on ivory slips and placed in a golden urn provided by Beijing. (I have read the urn is not actually gold, but copper.) When the time came, Tibetan lamas and the emperor’s representatives (ambans) would together draw one ivory slip. The urn to this day is kept in Jokhang Temple in Lhasa, although there is a duplicate in the Yonghe Temple in Beijing.

How much was this order actually followed? It’s hard to know, although no source I have consulted says it was followed scrupulously. There’s a consensus that its use was enforced for only a few decades. According to editor and author Alexander Gardner, “Tibetan, Chinese, and Western scholars have been debating over the extent to which the Urn was actually used ever since.” (“Treasury of Lives: The Controversy of the Golden Urn,” Tricycle, April 2, 2013) It’s also probable that the drawing was “rigged” at times. Gardner writes that the urn probably was used to choose the Eleventh and Twelfth Dalai Lamas. Some other sources say it was used to choose the Tenth also. But it was not used to choose the Ninth, Thirteenth, or Fourteenth. There is no historical imperative that the golden urn must be used to recognize a Dalai Lama.

The Golden Urn Today

Max Oidtmann, author of Forging the Golden Urn: The Qing Empire and the Politics of Reincarnation in Tibet (Columbia University Press, 2018), says that the revival of the golden urn ritual by the People’s Republic of China was a panicked response by some officials in Beijing to keep control of Tibet. The PRC revived the golden urn ritual in 1995 when, in accordance with older Tibetan tradition, six-year-old Gedhun Choekyi Nyima was identified as the Eleventh Panchen Lama by the Fourteenth Dalai Lama. Since the time of the Fifth Dalai Lama in the 17th century, the Panchen and Dalai Lamas have been instrumental in recognizing the rebirths of each other.

Three days later, the child and his family disappeared. They have not been seen since. The PRC maintains the probably fictional story that they are all alive and well somewhere and don’t want to be bothered. A few months later the PRC chose another child, the son of a loyal Party member, to be the Panchen Lama. China’s choice, Chökyi Gyalpo, is an ethnic Tibetan who has spent most of his life in Beijing. Now 33 years old, the PRC uses him as the “face of Tibetan Buddhism” in Chinese media. And of course he is a reliable mouthpiece of approval for China’s policies toward Tibet. When the time comes, Chökyi Gyalpo will be expected to take a leading role in the golden urn ritual that will reveal Beijing’s choice of Dalai Lama.

Postscripts

At the end of the Sino-Nepalese War, the Shamar tulku was found to have died. Exactly how is not known. The Tibetan government banned further recognitions of Shamar tulkus. The red ceremonial crown of the Shamar tulkus was buried under the Shamar’s monastery in Lhasa. And then the monastery was turned into a courthouse, so that people would walk over the crown. The lineage was resurrected in the 20th century. Today there is a Fourteenth Shamarpa, His Holiness Mipham Chokyi Lodro. I assume the red crown the Shamarpa wears on ceremonial occasions is a new one.

As some of you may have guessed, the Trungpa tulku in our story was a predecessor of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche (1940–1987), a Tibetan teacher who was hugely influential in western Buddhism. The current Trungpa tulku is His Holiness Choseng Trungpa. Chogyam Trungpa’s son Sakyong Mipham is also a prominent, and controversial, lama.