Britain invaded Tibet in 1903. The British did not intend to conquer Tibet but to warn Russia to stay out of it. British troops left Tibet in September 1904, believing they had made their point. But though this may be just a footnote of history, I say it’s a story worth telling. It reveals much about human nature, hubris, greed, confirmation bias, and the state of the world during a turbulent time.

The invasion was not Tibet’s first encounter with the British. A few British merchants had tried to do business with Tibet in the 18th century. A Scottish adventurer named George Bogle (1764–1791) established diplomatic relations with Tibet and befriended the Sixth Panchen Lama. But the early visitors were relatively benign. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries European powers were aggressively colonizing Asia as if they were entitled to it. The grand prize was China, and if nothing else Tibet looked like a big back door into China.

China was entering a period of chaos. The old arrangements between the Qing Dynasty and Tibet still existed on paper, but China couldn’t enforce them. The Boxer Rebellion, which attempted to drive all foreigners out of China, began in 1900. The Guangxu emperor (1871–1908) was the Chinese ruler of record, but the real power in China was his aunt, the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908). All the while, forces of rebellion against the Qing were building. The last Qing emperor, Puyi, would be forced to abdicate in 1912. The Emperor was six years old at the time.

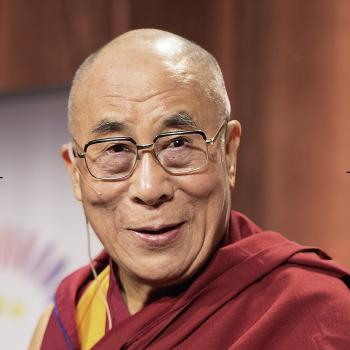

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama

At the time Britain invaded Tibet the Tibetan head of state was His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso (1876–1933). He is remembered today as the Great Thirteenth. He was the first Dalai Lama since the Fifth Dalai Lama (1617–1682) to head the Tibetan government through his adulthood.

To recap, the Sixth Dalai Lama (1683–1706) rebelled against being a Dalai Lama and died in the hands of Mongolian kidnappers at the age of 24. Because of the ensuing political upheaval, the Seventh Dalai Lama (1708–1757) held the reins of the government of Tibet for only the last seven years of his life. The Eighth Dalai Lama (1762–1804) preferred to let others run the government. The Ninth (1805–1815), Tenth (1816–1837), Eleventh (1838–1856), and Twelfth (1857–1875) didn’t live long enough to do much in the way of governing. It’s believed that at least some of those last four were assassinated by their regents.

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama is remembered as an intelligent and forward-looking leader, but in 1903 he still had a steep learning curve to climb.

The Great Game

When the Great Thirteenth began his rule of Tibet in 1895, the Russian and British empires had been sparring for decades over control of Asia. The British called this maneuvering over Asian territory the Great Game. By then Britain had incorporated the Indian subcontinent and much of southeast Asia into its empire. Through military aggression Britain also had achieved substantial control of Bhutan, Sikkim, and Nepal, which at the time were countries on Tibet’s southern border. (See this helpful map. Sikkim is the small area in between Nepal and Bhutan.) In effect Britain dominated Tibet’s entire southern and southwest border. The rest of Tibet’s border was dominated by Qing Dynasty China. This includes Mongolia, which at the time was ruled by China. And the Russian Empire was at China’s northern border.

British and Tibetans soldiers had first clashed, briefly, over Sikkim in 1888. Sikkim at the time was a Buddhist kingdom with deep religious and cultural ties to Tibet. By treaty, Sikkim had been a suzerain of Britain since 1861. This meant Sikkim had internal autonomy but allowed Britain to handle its foreign affairs. The Tibetans, meanwhile, considered Sikkim to be under Tibetan protection. In the mid 1880s signs of increasing British aggression caused Tibet to establish garrisons of troops in northern Sikkim. The resultant military action that is recorded in British history as the Sikkim Expedition ended with a Tibetan defeat.

In 1890 Queen Victoria’s government made a treaty with China regarding the borders of Tibet and Sikkim along with a trade agreement involving Tibet. No Tibetans were present at the negotiations. The British eventually realized these agreements were meaningless. Tibetans did not feel bound by them. And China wouldn’t and probably couldn’t enforce them.

Lord Curzon and the Russian Monk

George Nathaniel Curzon, also referenced as the 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, became viceroy of India in 1898. Curzon was a standard Victorian-era upper-class Brit who was certain that British colonial rule was for the good of the “natives.” He appears to have believed that the British empire was ordained by God to bring proper British civilization to Asia. Curzon further believed that Russia was the biggest rival and threat to Britain’s domination of Asia.

Lord Curzon decided that his goal of spreading British influence into Tibet required direct contact with the Dalai Lama. In his first three years as viceroy of India he sent three official letters to His Holiness in Lhasa. These were written on quality British stationary, with impressive wax seals, and carried to Lhasa by reputable intermediaries. They were all returned unread, which Curzon took as a snub of Britain.

But then Curzon began to hear reports that Tibet was talking to Russia. One of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama’s closest associates was a monk from Russia, an ethnic Mongol named Agvan Dorzhiev. The British in India came to believe that Dorzhiev was a Russian spy. In 1896 Dorzhiev traveled to Moscow and was presented to the Tsar. The Times in London reported that steps had been taken toward a bilateral alliance between Russia and Tibet. Lord Curzon was certain the Dalai Lama was plotting with Russia to free Tibet from China.

And Then the British Invaded Tibet

The British had already been sending spies to Tibet. These spies, who were Indian, were called pundits. This is a word coined from a Sanskrit word that means “learned man.” One of the pundits reported back to the British that Russia was sending shipments of firearms to Tibet. When the Tibetans realized there had been British spies among them they became more inflamed against Britain, which was a possible reason why letters were returned to Lord Curzon unread.

Lord Curzon was determined to send a military expedition into Tibet. But in 1899 Britain became engaged in the Second Boer War in South Africa, which was a disaster for Britain. Queen Victoria’s government wasn’t in the mood to approve other military adventures. But Curzon kept pushing. In 1903 he got permission from London to send some troops to an area called Khamba Dzong, just inside the Tibetan border, to begin direct negotiations with Tibetans. Curzon assigned the task of leading this expedition to his friend and associate Francis Younghusband.

Younghusband and 500 troops crossed the border into Tibet in July 1903 and demanded a meeting with the Dalai Lama. And then … not much happened. Eventually a Tibetan general, a Tibetan political official, and a Chinese amban (agent of the Qing court in Tibet) found Younghusband and told him nothing would be discussed until he and his troops withdrew back to Sikkim. And then, having delivered their message, they left. Younghusband cooled his heels in Khamba Dzong and looked for excuses to push further into Tibet. For example, in one letter he reported that the Tibetans were planning to invade India and were just waiting for the arrival of 20,000 Russian soldiers.

Better Excuses Were Required

Lord Curzon, meanwhile, was looking for more plausible excuses. His best shot, he thought, might be Tibetan violations of the border agreement that Britain had negotiated with China, which the Tibetans were ignoring. Or, if not that, any reports of Tibetans outside Tibet would do. When Tibetan yak rustlers cornered some yaks in Nepal and herded them back to Tibet, Curzon thought he had his chance. “We now learn that Tibetan troops attacked Nepalese yaks on the frontier and carried many of them off,” Curzon wrote to his superiors. “This is an overt act of hostility.”

The steady drip of news of the yak attack and similar violations of British propriety finally wore down the government of the new King Edward VII. The expedition received permission to go further into Tibet, as far as Gyantse — roughly 150 miles, or 241 km, from Lhasa. The purpose of this mission was to “obtain satisfaction,” which suggested restoring British honor. British journalists also began writing editorials about teaching the Tibetans their place. All this nonsense about returning official letters unopened and not respecting a perfectly good British-Chinese treaty had to stop.

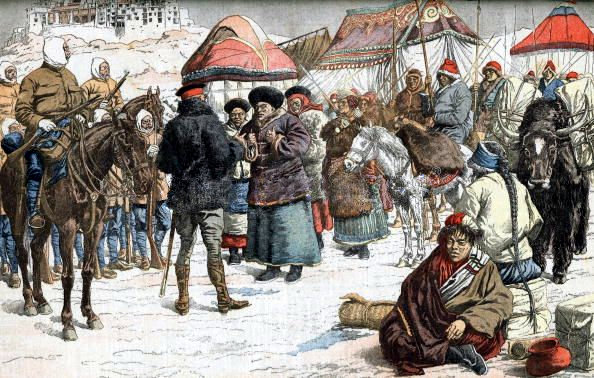

Younghusband and his 300 troops temporarily withdrew into Sikkim. And then on December 13, 1903, Younghusband entered Tibet again. This time he had 2,500 soldiers, mostly Gurkhas and Sikhs commanded by British officers. These were accompanied by 10,000 porters. Joining the enhanced expedition were reporters from the London Times and other newspapers, plus a few civilian adventurers who hoped to see the mysterious city of Lhasa. Cautiously the expedition began lumbering toward Gyantse.

The Battle Is Joined

The government in Lhasa could not agree what to do. One minister who had extensive experience in British India warned that Tibet didn’t have a chance against the army coming toward them, and they should call for negotiations. But others insisted that Tibetans were great fighters, and the British obviously were enemies of Buddhism. The pro-negotiation faction was in the minority and were ousted from the government. Tibet would defend itself.

In March 1904 the British expedition and 3,000 Tibetan troops came together at a place called Chumik Shenko. The British army in Tibet had modern firearms, including large, fully automatic machine guns called Maxim guns. The Tibetans who marched out to engage them had antiquated matchlock muskets and charms blessed by the Dalai Lama.

The Tibetans were quickly surrounded before a shot had been fired. Younghusband believed the Tibetans had surrendered, and he ordered the Sikhs to disarm them. But the Tibetan soldiers didn’t understand what was happening. Further, they owned their own firearms and were not inclined to give them up, even if they weren’t going to use them. At some point there was jostling, and a gun went off. The British troops opened fire. Tibetan soldiers fell where they stood. It was a slaughter.

On to Lhasa

The British expedition reached Gyantse, and the great monastery-fortress there was soon taken. The government in Lhasa realized, finally, they couldn’t fight the British. The Dalai Lama advised negotiation. Meanwhile, Younghusband pressed on to Lhasa. As the British approached Lhasa the Dalai Lama evacuated, riding on horseback toward Mongolia with a small entourage that included Agvan Dorzhiev. The seals of the government were left with the Ganden Tripa, the head of Ganden Monastery.

As the British army paraded through the streets of Lhasa they were met with clapping and cheering. Or what they thought were clapping and cheering. “In fact, the apparent greeting was actually a traditional method of bringing down rain and repelling evil spirits,” writes Sam van Schaik in Tibet: A History (Yale University Press, 2011). “As one amused Tibetan noted ‘In the foreigner’s custom these are seen as signs of welcome, so they took off their hats and said thank you.'”

What Younghusband did not find in Lhasa, however, was anything Russian. There were no Russian arms, no Russian troops, not so much as a single Russian tourist. His certitude in Russian interference in Tibet had been a mirage.

The Completion of the Mission

The Ganden Tripa readily agreed to Younghusband’s terms, which primarily were to not engage in treaties with other foreign powers (like Russia), to allow British garrisons at the border, and to permit a British trading post in Gyantse. He and the Chinese amban at the negotiations also promoted the idea of deposing the Dalai Lama, which of course the Tibetans ignored. And then the British packed up and returned to India.

When all was done, King Edward VII’s government was not pleased with Younghusband. He had overstepped his orders, Younghusband’s superiors said. And Britain did not want to be tied to Tibet in perpetuity. The terms of the agreement signed by the Ganden Tripa were watered down, so that the only lasting effect as far as Britain was concerned was that two British trade agents and a telegraph wire were installed in Tibet.

The other effect was a huge loss of face for Beijing. In earlier times invaders into Tibet faced the Qing emperor’s troops. But the Qing court was so weakened it did nothing about the Younghusband expedition. “The restoration of national security and national pride would play a huge part in the Chinese approach to Tibet in the twentieth century,” Sam van Schaik wrote.

His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama did not return to Lhasa until 1909. During that time he traveled quite a bit, even to Beijing, and tried to learn about the wider world. When he did go back to Potala Palace there was peril at hand. You can read about the Dalai Lama’s next escape from danger in the next post, Tibet’s Declaration of Independence and the Thirteenth Dalai Lama.