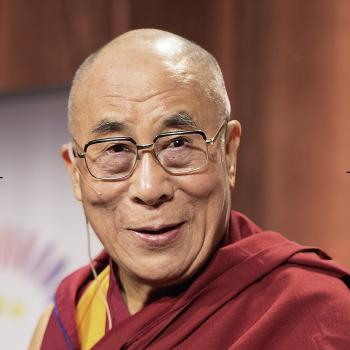

The Dalai Lama escaped Tibet in March 1959, 66 years ago this month. March 1959 was a pivotal time in Tibetan history. At the beginning of the month the young Dalai Lama was emersed in studies for his final exams in Buddhist teachings. As far as anyone can tell, on March 1 he was giving no thought to leaving Tibet. But on March 31, he crossed the border into India, seeking refuge. This began his long exile from Tibet, which continues to this day. What happened? In brief, the Dalai Lama escaped Tibet because the Chinese occupation of Tibet, which had begun in 1950, had taken a dark and violent turn.

First, just a quick note on Dalai Lamas. There is a lot of confusion and misinformation about the Dalai Lamas in the West. They were never “god-kings” in old Tibet, as you may have heard. Although a succession of Dalai Lamas were considered the heads of state of Tibet since the 17th century (see “How the Fifth Dalai Lama Became the Ruler of Tibet“), in truth the Dalai Lamas have had limited authority even outside their own denomination of Tibetan Buddhism. And for various reasons most of the Dalai Lamas after the Great Fifth were figureheads and not really running the government. The exceptions were the Seventh (briefly), the Thirteenth, and the Fourteenth. But until the 1950s Tibet was a feudal society primarily run by a wealthy aristocracy. When the Great Thirteenth attempted to modernize Tibet, opposition from the aristocracy put a stop to most of his plans. So much for being a “god-king.” Even so, the Dalai Lamas are revered as the living embodiment of the Tibetan people, their history, and their Buddhist culture. For more detail on the role of the Dalai Lama, see “The First Dalai Lama.”

Background: China’s Claim to Tibet

When Chinese leader Mao Zedong sent an army to occupy Tibet in 1950, he justified the invasion by claiming that Tibet had “always” been part of China. Is that true? Tibet and China had a complicated relationship for several centuries, and China did often meddle in — but did not directly control — Tibetan internal affairs. Tibet was important to China as a buffer on its western border. From time to time China sent troops into Tibet to meet some threat. But when the danger had passed, the troops were withdrawn back to China and the Tibetans were left to themselves again. Further, through the centuries Tibet did not pay taxes or tribute to China. And when a Dalai Lama visited China, he was respected as a visiting head of state.

Some references (including some AI references) will tell you that Tibet was ruled by the Qing dynasty of China from 1644 to 1912. That’s certainly what China would like us to believe. But my primary source for Tibetan history says otherwise. Sam van Schaik’s Tibet: A History (Yale University Press, 2013) describes the relationship between Tibet and the Qing in great detail, and makes the Qing dynasty into more of a nosy neighbor of Tibet than a ruler. The succession of Dalai Lamas and rulers of China also had a personal patron-priest relationship going back several generations. For more background, see “China’s Claim to Tibet and the Seventh Dalai Lama” and “The Golden Urn and the Succession of Dalai Lamas.”

And then the Qing dynasty fell in 1911, and the Republic of China was established. In 1912 the Thirteenth Dalai Lama issued a declaration of independence, saying that Tibet had a relationship with the Qing dynasty, not the nation of China. And with the Qing dynasty dissolved, His Holiness said, so was the relationship between China and Tibet. And that’s where matters stood until 1950.

1950: China Invades Tibet

In October 1949, Mao Zedong declared victory in China’s civil war. The Tibetan government immediately began seeking allies who might help them repel a Communist invasion. They turned to the British, then to India, and then to the United States. But no help was offered. China made no secret that it planned to “liberate” Taiwan, Hainan, and Tibet from British and American imperialists. In fact, there were no Americans and only a couple of British nationals — a trade agent and a telegraph operator — living in Tibet at the time. But Mao Zedong had grand plans to expand China.

In October 1950, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of China advanced on Tibet. Tibet at the time consisted of three provinces: Central Tibet (Ü-Tsang), with its capitol city of Lhasa, was the part that had long recognized the Dalai Lama as its head of state. East of Central Tibet were two smaller provinces, Kham and Amdo. These had their own governments. Most of the people of those provinces were loyal to Tibetan Buddhism and the Dalai Lama as a religious figure, but they had little connection to the government in Lhasa.

The PLA first marched into Kham and Amdo, and the much smaller and poorly trained Tibetan military force in those provinces was no match. And according to Sam van Schaik, many of the Khampas sided with China. Then began a period of negotiation. Mao Zedong wanted the PLA to march into Lhasa unopposed, so he could proclaim a “peaceful liberation.” There was always, of course, the understanding that if Tibet didn’t agree to China’s terms, a violent invasion could still happen.

Eventually, in May 1951, the “Seventeen Point Agreement” was signed by a Tibetan official who wasn’t authorized to do so by anybody, but China proclaimed it a done deal. The Seventeen Point Agreement claimed the Tibetans sought liberation from foreign imperialist powers so they could “reunite” with the Motherland — the People’s Republic of China. Most of the government of Tibet didn’t know about the Seventeen Point Agreement until the officials heard a Chinese radio broadcast proclaiming they had agreed to it. But they realized they were in no position to oppose what had happened. And soon the PLA peacefully marched into Lhasa.

The Fourteenth Dalai Lama and Mao Zedong

When China invaded Kham and Ando in October 1950, His Holiness Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, was 15 years old. He had not yet stepped into the role of head of state. The government at the time was administered primarily by a four-person council called the Kashag. There also was a high-level senior monk who functioned as the Dalai Lama’s mentor and regent. Although traditionally the Dalai Lamas did not assume their governing authority until the age of 18, Tenzin Gyatso was formally invested with the authority to govern Tibet in November, 1950, at only 15. Of course, what governing he did was under China’s thumb.

The long-cloistered, adolescent head of state was suddenly thrust into a situation that would have challenged any senior statesman. He chose to be cautious. Mao Zedong had planned to win over the Tibetans gradually. At first, the Chinese “courted the Tibetan aristocrats and did little to change the old hierarchical social system in Tibet,” Sam van Schaik writes. In 1954, the Dalai Lama and several other eminent Tibetans were invited to Beijing by Mao Zedong. Mao made a special effort to win over the young Dalai Lama. When he returned to Lhasa, the Dalai Lama told Tibetans that China could help them modernize, finally, and that they should welcome reform.

What Went Wrong?

Very briefly, for a time Mao’s direction to let the Tibetans change gradually was followed, but only in Central Tibet. In the provinces of Amdo and Kham, the generals in charge pushed for quicker, top-down change. Especially in Kham, where every man carried a gun or sword, the push to collectivize all the farms brought on a violent resistance. In 1955, Khampas began to attack and kill Chinese. The PLA came to put down the rebellion. Many Khampa fighters took shelter in the large monasteries. In February 1956, a major monastery in Kham, Sampeling, was bombed into ruins, killing hundreds of monks and laypeople. Another large monastery, Litang, was bombed a short time later.

Many Khampas left Kham and headed for Lhasa. By 1957, the uprising that had begun in Kham had spread to Central Tibet. To make a long and complicated story a whole lot shorter — for a time the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government opposed the rebellion, but they had no army and there was little they could do about it. At the same time, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agendy began to get involved in the rebellion. The CIA soon abandoned its initial plan of influencing the Dalai Lama (who was never a CIA agent, no matter what longstanding claims on the Internet say) and instead they worked directly with the rebellion. The CIA was training Khampas in Taiwan and making covert arms shipments into Kham. As the rebellion grew more successful, public opinion turned in its favor.

As they began to face more effective armed resistance, the Chinese responded by rounding up even pro-Communist Tibetans who had blamed ham-handed Chinese policies for the rebellion in Kham. When a leading Communist Tibetan who was also a friend of the Dalai Lama was imprisoned in Beijing, the Dalai Lama finally began to question Mao Zedong’s true intentions for Tibet. The situation became more extreme, and dangerous, when Mao Zedong initiated the Great Leap Forward in 1958. This was a massive miscalculation on Mao’s part that would cause the deaths of an estimated 30 million Chinese. And it made the situation in Tibet much more desperate. The Chinese began to arrest monks, including senior lamas, suspected of favoring the rebellion.

The Breaking Point, and the Escape

Throughout the Chinese occupation, the Dalai Lama was still a young Buddhist monk and still expected to finish his studies in Buddhism. In March 1959 he faced his final exams, which involved many processions and ceremonies and cross-examinations by Tibet’s most learned monks. After the successful completion of the final exams, the Dalai Lama was invited to a celebration at the PLA headquarters, where a Chinese dance troupe was to perform in a large auditorium. And it was suggested His Holiness attend without his usual bodyguard.

The invitation set off rumor alarms throughout Lhasa that the Chinese were planning to arrest or assassinate the Dalai Lama. Monks close to the Dalai Lama begged him to not go, but His Holiness did not believe he was in danger. On March 10, people began to gather around Norbulingka, the summer palace where His Holiness was staying. They were determined to not let the Dalai Lama leave to visit the Chinese headquarters. As rumors intensified the crowd grew violent. Years of frustration at being occupied by Chinese soldiers boiled over. A couple of prominent Tibetans known to be working for the Chinese were attacked; one was beaten to death. And the Dalai Lama was trapped inside the palace. But eventually he got word to the crowd that they could disperse. Some remained to guard the palace; the remainder marched off shouting “Chinese out of Tibet!”

Over the next few days demonstrations broke out all over Lhasa, while the Dalai Lama remained inside Norbulingka. On March 17, two artillery shells were fired from the Chinese camp toward Norbulingka. The shells did not damage the palace, but it persuaded the Dalai Lama that he needed a new plan. He consulted the Nechung Oracle, who told him, “Go! Go now!” The Dalai Lama’s officials and family members — his mother, sister, and younger brother — disguised themselves as pilgrims to get past the crowds outside Norbulingka without being recognized. After nightfall, the Dalai Lama himself left, dressed in a Chinese soldier’s uniform, or perhaps a long, black cloak — sources disagree. The Chinese had been persuaded the Dalai Lama was not planning to leave Lhasa, and so no soldiers were watching for him to try to escape. Two days passed before the Chinese realized he was gone.

And the Dalai Lama Escaped Tibet

According to the April 20, 1959 issue of Time magazine, the entourage that marched or rode on horseback from Lhasa to India included 75 officials, soldiers, and mule drivers, with 35 armed Khampas in the rear guard. The article mis-describes Buddhist rebirth rather badly and incorrectly calls His Holiness a “God King,” so I don’t know how accurate this description is. Other accounts say the Dalai Lama’s mother and two younger siblings were also in the caravan, which navigated Himalaya mountain passes in sometimes freezing weather. Mountain mists and low clouds hid the caravan from Chinese planes.

According to Sam van Schaik, two of the armed Khampas had trained with the CIA in Taiwan and had a radio transmitter. The Dalai Lama used the radio transmitter to contact Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru of India to ask for asylum in India. The Prime Minister granted asylum. “Despite later claims from China,” writes van Schaik, “this seems to have been the only direct role played by the CIA in the Lhasa uprising and the flight of the Dalai Lama.” I bring this up because one does run into accounts, including AI accounts, that claim the CIA was much more directly involved in the Lhasa uprising and the escape to India. I suspect this is Chinese propaganda that AI doesn’t know to filter out.

Since 1959 the Fourteenth Dalai Lama has lived in Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh, India. If you’re curious about what Dharamshala is like, here’s a video. His Holiness will be 90 years old on July 6, 2025. In 2011 he relinquished all claim to political power, which is binding on any future Dalai Lamas. His hope is that someday a free Tibet will have a democratically elected government. He recently wrote a opinion piece published in the Washington Post headlined “My hope for the Tibetan people.” Even if Tibet remains part of China, he hopes the Tibetan people can keep their language, their identity, and their culture going forward. “I hope that the Beijing leadership will, in the near future, find the necessary will and wisdom to address the legitimate aspirations of the Tibetan people,” he writes. “To all those who have consistently stood by us, especially the people and government of India, thank you for your solidarity in our long, peaceful struggle for freedom.”