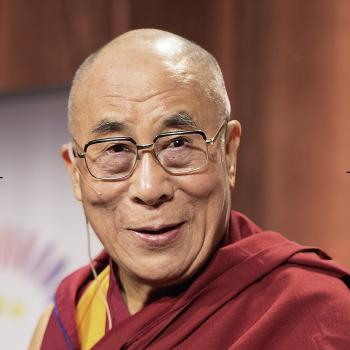

Tibet’s declaration of independence is a statement released by His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso (1876–1933), on February 13, 1913. In this statement the Dalai Lama said that Tibet’s long-standing relationship with China had been one of priest and patron, between Tibetan Buddhism and the succession of Qing emperors, not with the nation of China. With the fall of China’s last imperial dynasty and the establishment of the Republic of China, “the patron-priest relationship has faded like a rainbow in the sky.” All agreements and understandings that had existed between Tibet and the Qing Dynasty were dissolved. Tibet was completely independent of China.

Over the last few posts, beginning with How the Fifth Dalai Lama Became Ruler of Tibet, I’ve been exploring the lives of Dalai Lamas and the complicated relationship between Tibet and China over the past few centuries. This relationship is made more complicated by the fact that through most of this period the modern concept of the nation-state, a place with clearly defined borders and subject to international rules about sovereignty, hadn’t yet developed in Asia. So it’s difficult to explain what that relationship was in modern political terms. At no point before the 20th century did China rule Tibet outright, although neither did China leave Tibet alone. But the Thirteenth Dalai Lama’s main point, that the relationship was between Tibet and the Qing emperors, not the nation of China, seems accurate to me.

In this post we’ll pick up from the last post, “When Britain Invaded Tibet,” and review the events leading up to the writing of Tibet’s declaration of independence.

The Dalai Lama’s Escape from Lhasa

His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama left Lhasa in 1904 in advance of an invasion of British troops. He remained away for a long time even though the British did not stay in Lhasa. He spent a couple of years as the guest of the Jetsun Dampa, the highest reincarnate lama of Mongolia. During that time the Dalai Lama’s close associate, the Russian-born monk Agvan Dorzhiev, went to Moscow to ask the Tsar for protection from British aggression. Agvan Dorzhiev, as they say, got the runaround. The Russians made sympathetic noises but no commitments.

In 1906 the Dalai Lama moved on to Kumbum monastery in Amdo, a region of northeast Tibet (see map). There he could enjoy the company of Buddhist scholars and find time to write poetry. But south of Amdo is Kham, another region of Tibet. An agent, or amban, of the Qing emperor in Kham initiated new land policies to which the Khampas — people of Kham — objected. There was an uprising. The end result of this was that Chinese troops marched into Kham and put Kham under direct Qing rule for the first time.

The news of the fall of Kham reached the Dalai Lama shortly before he received disappointing news from Moscow. Britain and Russia signed an agreement in 1907 in which Russia agreed to recognize Britain’s “special interest in the maintenance of the status quo in the external relations of Tibet.” There would be no help from Russia. The Thirteenth Dalai Lama decided he must speak to the Emperor of China directly about Kham. With a great entourage he left Amdo and headed for Beijing.

The Dalai Lama in Beijing

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama reached Beijing in autumn 1908 and was met with indifference. His only audience with the Guangxu Emperor was polite but unproductive. When he said he wanted clarification of Tibet’s relationship with the Qing court, he was told to go back to Lhasa and submit his issues to the amban there.

In truth, at that point the Guangxu Emperor was not really ruling China. The de facto ruler of China was his aunt, the Empress Dowager Cixi, who seems to have ignored the Dalai Lama until she became ill. She then asked him to conduct a long-life ritual for her, which he did. But her condition worsened. The Guangxu Emperor died, unexpectedly, on November 14, 1908, and the Empress Dowager promptly named a two-year-old boy of the imperial family as his successor. The next day, the Empress Dowager also died. Decades later forensic examination of the Guangxu Emperor’s remains determined that he died of massive arsenic poisoning. It’s assumed the Empress Dowager poisoned him so he wouldn’t take power after she died.

The Dalai Lama must have realized he would get nowhere in Beijing, and in December 1908 he began the return trip to Lhasa.

The Dalai Lama’s Escape to India

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama arrived in Lhasa on December 25, 1908. Shortly after he arrived, posters began to appear all over Lhasa declaring that Chinese soldiers were coming to protect them from foreign invaders. By then, as far as the Dalai Lama was concerned, the only foreign invaders he needed to worry about were the Chinese. In February 1909, 2,000 Chinese troops marched into Lhasa from Kham. The Dalai Lama believed, with good reason, that China intended to capture him. One February night the Dalai Lama and some officials who supported him quietly left the Potala and rode on horseback out of Lhasa toward India. He had no particular reason to trust the British, but he had no other options.

It was a hard journey through icy mountain passes and heavy snows. Eventually the Tibetans arrived at a British telegraph office in Sikkim. The two British soldiers manning the office were awakened in the middle of the night by a pounding on the door and Tibetans proclaiming “Dalai Lama! Dalai Lama!” The soldiers gave His Holiness some hot tea and let him sleep in one of their beds. The next day the Tibetans moved on to India and arrived in Darjeeling only nine days after leaving Lhasa. Local officials put the Tibetans up in a hotel.

The Dalai Lama was tired and unwell, but his fortunes were about to improve a little. In Darjeeling he met Charles Alfred Bell (1870–1945), the British political officer for Bhutan, Sikkim and Tibet. Bell spoke Tibetan and was genuinely sympathetic to the Tibetan cause. Bell and the Dalai Lama became lifelong friends.

Tea and Sympathy, But No Help

After he had recovered from the journey to India, His Holiness with Charles Bell traveled to Calcutta to meet the new viceroy of India, Gilbert John Elliot-Murray-Kynynmound, 4th Earl of Minto. His Holiness told Lord Minto about the Chinese aggression in Lhasa and asked for help from Britain. He was the legitimate head of government in Tibet, the Dalai Lama said, even if he was a government in exile. But in May 1910 a telegram came from London advising that “there can be no interference between Tibetans and China on the part of His Majesty’s Government.” When Charles Bell broke this news to the Dalai Lama, the Tibetan was so profoundly disappointed that for a short time he could not speak. But even after this he trusted the British more than he trusted China.

Meanwhile, in Lhasa, there were orders to depose the Dalai Lama in his absence and choose a new one using the golden urn. The amban in Lhasa chose not to carry this out, probably fearing an uprising. But he did go ahead and replace government officials with Chinese and Tibetans loyal to China. The amban also took over running the police and the courts. After all these years this was the first attempt by China at direct rule of Tibetan internal affairs.

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama spent the early months of 1911 touring sacred Buddhist sites in India. The British government provided transportation, including a motor car and a private train. In Bodh Gaya, the place of the Buddha’s birth, he saw the impressive Mahabodhi Temple that had been restored by the British government with the help of British engineers. The British were not Buddhists, but perhaps they weren’t enemies of Buddhism.

The Fall of Qing; the Liberation of Lhasa

The impasse in Lhasa would be broken by events in Beijing. In October 1911 the Qing government collapsed after a series of mutinies. On hearing the news Chinese troops in Lhasa mutinied also, against the amban, and began looting the city. Tibetans fought back. The Dalai Lama sent a trusted official to Lhasa to help organize the resistance. The British government warned the Dalai Lama to not encourage fighting in Tibet. The Dalai Lama replied, “We must fight for the religion and our own freedom.”

The Dalai Lama moved back to Sikkim, near the Tibetan border, where he could receive news and send orders. Lhasa became divided into Chinese and Tibetan war zones and a scene of brutal street fighting. Not all Tibetans supported the Dalai Lama. For example, the Panchen Lama (Tibet’s second highest lama), who had become close to the amban, sided with China. But the Chinese were cut off from supplies and reinforcements. By 1912 they were isolated in Tengyeling Monastery until they were out of supplies. And then they were deported to China, as were other Chinese in Tibet over the next several weeks.

By June 1912 the Dalai Lama was back in Tibet. He had to stay out of Lhasa until the terms of surrender were worked out and all Chinese had left. Then in January 1913 the Thirteenth Dalai Lama walked through the gates of Lhasa and returned to Potala Palace.

Tibet’s Declaration of Independence

The statement the Dalai Lama released on February 13, 1913, was both a declaration of independence for Tibet and a declaration of his own authority to rule Tibet. It includes the Dalai Lama’s understanding of recent events.

During the time of Genghis Khan and Altan Khan of the Mongols, the Ming dynasty of the Chinese, and the Ch’ing [Qing] Dynasty of the Manchus, Tibet and China cooperated on the basis of benefactor and priest relationship. A few years ago, the Chinese authorities in Szechuan and Yunnan endeavored to colonize our territory. They brought large numbers of troops into central Tibet on the pretext of policing the trade marts. I, therefore, left Lhasa with my ministers for the Indo-Tibetan border, hoping to clarify to the Manchu emperor by wire that the existing relationship between Tibet and China had been that of patron and priest and had not been based on the subordination of one to the other. There was no other choice for me but to cross the border, because Chinese troops were following with the intention of taking me alive or dead.

On my arrival in India, I dispatched several telegrams to the Emperor; but his reply to my demands was delayed by corrupt officials at Peking. Meanwhile, the Manchu empire collapsed. The Tibetans were encouraged to expel the Chinese from central Tibet. I, too, returned safely to my rightful and sacred country, and I am now in the course of driving out the remnants of Chinese troops from DoKham in Eastern Tibet. Now, the Chinese intention of colonizing Tibet under the patron-priest relationship has faded like a rainbow in the sky.

The Republic of China, which followed the Qing Dynasty, claimed ownership of Tibet but was unable to exert that claim.

Postscript

On his travels outside Tibet the Thirteenth Dalai Lama became aware of how far behind the rest of the world Tibet had fallen. In the early 20th century Tibet was still, more or less, a feudal society. Tibet had no modern schools or hospitals, no electricity, no telephones, no motor cars or trains. The Dalai Lama wanted to lead Tibet into the modern world. For example, while he was still living in India he worked out arrangements for a few Tibetan boys to be educated in England so they could return to Tibet and teach. One of his first acts after resuming power in 1913 was to begin building a new medical college.

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama also established a secular school system and introduced criminal justice reforms. He made an attempt to clean up corruption in the monasteries. He built a hydroelectric plant. And he began to upgrade the Tibetan military, with a regular army that had British arms and whose officers trained in India with the British military. Tibet at first had to purchase the arms, because the British didn’t want to take sides between Tibet and China. But Tibet was broke. To raise money for his reforms, the Dalai Lama began to tax the wealthy nobility, the landowners. This did not go over well, and the nobility pushed back against his reforms. And part of the Buddhist establishment was opposed to the secular schools and his anti-corruption reforms.

We in the West have been told the Dalai Lamas were “god kings” in Tibet with absolute power. If you’ve been reading this series on the lives of Dalai Lamas, by now you know that was never true. After a few years the Thirteenth Dalai Lama had scaled back many of his plans because there was too much opposition. Much of the Tibetan religious establishment and the monied nobility liked things the way they were before the 20th century, thank you. Before he died in 1933 he issued a warning that it was only a matter of time before China attempted to conquer Tibet again, and Tibet had better be prepared. But Tibet would not be prepared.

For more on the history of Tibet and the lives of Dalai Lamas, I recommend Tibet: A History (Yale University Press, 2011) by Sam van Schaik.