Something I loved about Rogue One was how haunted by the Jedi that universe is, how the ghosts of the Jedi seem to follow the characters around. Even if the most powerful living embodiment of religion had been eradicated, still no one could quite rid themselves of its ghost.

We also get to see non-Jedi be religious, get to see them be devoted to the Force in their own ways. Jyn, the central protagonist, has a mother who gives her a kyber crystal when she is very young, telling her to trust the Force. We meet a character (Chirrut Îmwe) who literally prays to the Force. And so it goes. The Jedi are dead, but the Force is not, and the Jedi tied themselves so intimately to the Force that their old sacred sites remain powerful.

I love a universe haunted by religion. That Star Wars is a universe haunted by a dead religion makes it, in many ways, an excellent image of what it is to be religious in the modern world.

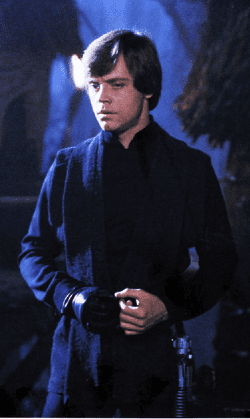

When I was growing up, my favorite thing about the Star Wars universe was the Jedi. The prequels did not exist yet, and so all anyone knew of the Jedi was that they were once great and now were long gone, with only Obi-Wan and Yoda standing as living relics of what once was. Even Vader, in his way, was a living – if fallen – witness to everything he himself had wiped from the galaxy.

Imagining myself with great powers and a lightsaber was hugely appealing, of course, but I have these oddly distinct memories of being fascinated by the vanished religion itself. For its mysticism. What did it mean for Luke to walk through the dark trees and find his own face staring back at him? Who were these people for whom such visions were a vivid part of life? I almost missed the Jedi, though I’d never known them at all. The myth tugged at everything dangerously nostalgic in me, this tendency I had to look back through the mist of ages for a lost perfection. Even when I was young, I liked stories of a past I had never known. I could bury myself there, sinking my hands into the rich earth in a fierce search for hope.

If the past has no hope in it, after all, then neither does the future. Much as we would wish to cut ourselves off from what seems to have failed, from a past littered with fallen Star Destroyers and dreams, there is no other soil from which to grow. Unlike God, we cannot create out of nothing.

The danger is losing ourselves in the past. This can mean ignoring the present, or it can mean trying to force the present to be the past, which of course it cannot be. I think dimly of Kylo Ren staring at the broken mask of Darth Vader, wishing to be him. Or, outside of Star Wars, I imagine those of us who want things to be as they once were, exactly as they once were. Or some other variation.

I remember when I discovered the section of my college’s library that houses a considerable, if quite old, collection of the writings of the Church Fathers. Dusty translations and dustier Latin, Greek. They reside in the corner of the top floor, several aisles crowded together. Tears stung my eyes as I wandered among the books, fingers touching the names. Irenaeus, Hilary, Clement, Athanasius. I remember sitting on the floor of the library and crying, because I had finally found a place on campus that felt like home. These Fathers speak the language of the Christianity that I love fiercely, that I recognize as my native land. They sing of a place that feels warm, real, safe. And I cried harder because they’re all books, and they’re all dead.

As a modern Catholic, I sometimes feel myself born into a twilight that I’ve never been able to understand. The greatness of my religion is often quite hidden, but still very real, and our deepest achievements often happened quite long ago. It is a strange thing, to be a part of something two-thousand years old. To begin to think in those terms, to begin to feel history stretch out wide and endless. The 19th century is perhaps long ago to many people, but it is not to the Catholic Church.

I say “twilight” with weary caution, if only because I know I can be misunderstood. I do not imagine that the Church is dying, or that she will at some point be dead. But it does sometimes seem that we are living in the midst of a dying of some kind. Perhaps we always have been: ever dying unto Christ. I never know what I am trying to name, when I try to name this thing that I feel.

I do know that I prefer a universe to be haunted rather than one that is not. I don’t know that perfect amnesia is ever possible to us. I shudder at the possibility. And in that galaxy far, far away, I think we see a dim image of ourselves. They are haunted by the Jedi, and it gives me a strange sort of hope.