To Be A Kumare?: A Socio-Religious Critique of Kumare

An Abject Expression

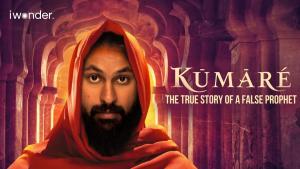

Vikram Ghandi took on the personality of “Kumare,” a fictitious guru who led non-believers toward a sense of enlightenment and personal transformation vis-a-vis his Hindi religious-social-cultural background. Framing this pseudo character, Kumare, against a stereotype of East Indian culture, Vikram was, then, able to translate a fashioned religious identity ambivalent of the space-place of a personal conscious identity. Marketed mainly to non-East Indian consumers, the Kumare character opens the dialogue for how religion, culture, and stereotypes are consumed. An American ethic framed along a product-consumption binary provided Ghandi an established platform to project and market a fantasy of an “other” race, culture, class, and society. “The True Story of a False Prophet,” is the subtitle of the film. Approaching this “Spiritual Placebo Effect,” (Ghandi, para. 6), an abjective response to the American dialectic of race, culture, socio-religious stereotypes come into focus. A singular lens analysis will miss the multifocal connections stated in Kumare. The question, “How or why do those who connected with the Kumare character arrive at a point in their lives where they seek the need to better their emotionally unstable environments through a sense of contact with a higher power?” The analysis of this perspective demands a critical review of an abject reading of the intersections of race, culture, and socio-religious stereotypes.

An Expression of Case and Affect

Dr. Saad, in Psychology Today, states the following, “New Age gurus…dispense meaningless drivel that masquerades as profound truths whilst in reality, it is a mere exercise in obscurantism” (Saad, para. 3). Dr. Saad develops his argument on how mechanical and simple generating a prototype identity around a cultural stereotype can be using, compassionate intentionality, a transfiguration of identity along a presumption of a stereotyped norm, and a convergence of socio-religious extra-ordinary contexts (Saad, para. 3). Following this process a mechanical derivative of culture is applicable to any environmental situation where a minimal understanding of reality is coupled with a desire to escape a banal inner circumstance. An abject reading – how minimal a viewpoint is maintained by one’s inner sense founded on external beliefs consumed yet not questioned – positions the Kumare character perfectly in line with a lower-class ethic in the American mental landscape. It’s important to recall that Kumare was produced specifically to challenge a status quo mentality and a commercial ethic marketed to a middle-class American identity. The product-consumption binary was prescribed by a failing modernist/post-modernist American dialectic. Kumare capitalized on the consumer attitude selling a socio-religious fallacy to this open market. The subsequent reach of Kumare became an idol, a fixture of a fantasy master spiritual departure. The use of an emblem, Kumare’s staff topped with a phony insignia, served as much of a cloaking device as did his yoga possess and fake physical gestures his “followers” performed.

Those who freely elected to ingest the Kumare character applied their willingness to be pseudo-satisfied with a socio-religious dialectic machine that not only acquired fame and monetary gain but more to the point, gained their emotional and spiritual investment. These “followers” cooperated robotically along the lines of an extended Stockholm Syndrome – positive feelings toward an abuser or captor (Thompson, para.1). Extending this analysis, those “followers” became believers of Kumare. They qualified his fictional character by placing positive feelings and cooperative attitudes toward his socio-religious fallacy. This operation is what inverted Ghandi’s own perspective of the Kumare character. It is at this point where the emotional, spiritual captor began to value positive feelings for the Kumare character. The inverse of the Stockholm Syndrome – a typical external expression – took place for Ghandi. He internalized the positive qualifications, attitudes, and feelings from the “followers” to the point where he was caught in an ambivalent state of identity dysfunctionality. Ghandi embodied the physical nature of Kumare, yet he had, to this point of capitalist fame and spiritual, emotional, socio-religious accolades, remained psychologically removed from the fictional identity. The “followers” of Kumare, then, reversed the Stockholm Syndrome of Kumare on the psychology of Ghandi creating the inner struggle that eventually succumbed and destroyed the Kumare identity. Ghandi decolonized his mental and emotional contact with the Kumare fantasy so to save his own fall toward an abject reality.

A Closing Expression

Vikram Ghandi took a bold step in recording his external situations and reading them through his cultural lens. Ascertaining the stereotype of East Indian culture already contextualized in the American market, Ghandi was able to harness this ethical misunderstanding and misrepresentation of identity and social structure. Kumare was set in motion as the “Spiritual Placebo Effect.” The outcome was an ambivalent reading of socio-religious product-consumption mechanically aligned with a faulty rhetoric of East Indian identity. Ghandi originally questioned the spiritually devoid. He set his design of the Kumare experiment to unpack the need for a spiritual direction. The package commodity of the Kumare experiment followed the baseline construction of an idol identity birthed from a fallacy. Ghandi did not stray away from the embodiment of the abject nature of the Kumare character; he embraced all the inaccuracies of the socio-religious identity. The juncture of product-consumption eventually brought Ghandi to the point where he could not disenfranchise his reality with that of the acquired attention and status marker of Kumare, thus falling into his own Stockholm Syndrome. The question of how spiritually dependent one needs to be to follow a cultural contradiction is, by example the Kumare character, more determined by external market aesthetics, inaccuracies of culture, and the product-consumption of a socio-religious icon/idol/identity.

Alan Lechusza