So You Want To Write a Grunge-style Christian Song?

Going to battle for your faith is not a new prospect. There are multiple stories in Christianity where this action takes place. To “wear the armor of God,” is more than a metaphor. It holds full value with a faith-based core.

Therefore put on the full armor of God, so that when the day of evil comes, you may be able to stand your ground, and after you have done everything, to stand. – Ephesians 6:13 NIV

As prominent as this phrase eludes, how modern Christian sounding artists frame this perspective points to creativity while not reducing the importance of the scripture.

Christian and faith-based music has evolved to engage popular music genres, sounds, styles, and visuals. An underscored complication with these industry-standard adjustments is how to retain a faith-based creative work. The gravitational pull of pop culture can orchestrate how an artists/band configures their works from meager root-origin beginnings to the demand for larger audiences, appeal, and record sales. Enter the complication to retain a firm faith-based ethic in a consumer-driven globalized markets environment. Not an usual progression for an artist/band to advance their work, but a bit more disciplined for those committed to retaining a Christian faith-based image, sound, and testimony.

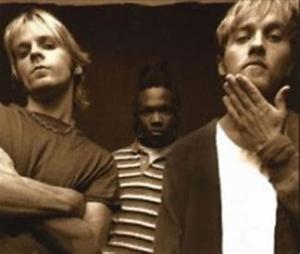

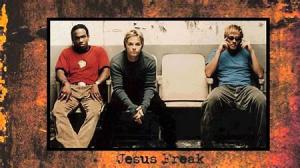

The band DC Talk has endured this journey with critical and audience acclaim. DC Talk (“Decent Christian” Talk) was formed in 1987. A career ranging five records deep, the band has since settled on solo adventures with marginal collaborations since 2000. Early attention was shed on their Hip Hop/Pop sound from the late 1980s through early 1990s. Their 1995 release “Jesus Freak” articulated a pivot point for the trio from their early firm Hip Hop/Pop stance.

The work, I argue, does less to support a sounding apologetic view of Christianity than be function as an outlier for confusion about following a faith-based Christian doctrine.

Music is a powerful force. The timber of the track is clearly marketed for a grunge, Gen X audience. Release in 1995, the band states,

“After three albums of hip-hop and pop-oriented sound,… the trio decided to innovate and reinvent their style. After three years (1992 – 1995), DC Talk returned with songs featuring a more alternative rock sound. Thus, the album’s lead single, “Jesus Freak”, was considered unexpected by fans and critics alike. Michael Tait said, “I was totally into rock and roll at the time […] I really wanted to make a rock record. “The band decided to focus on more rock-oriented music, with touches of rap and pop interwoven into the mix. Tait later explained, “We wanted to write songs that would hopefully touch a generation.”

The shock-and-awe of this record was not only felt by long-standing fans, but by others who would otherwise not know about the history of the band.

The visual representation of the work fairs little in the way of supporting a “decent Christian” dialogue. Creating a new sound is not a new adventure for a band. Sculpting a sound to meet the zeitgeist of the generation is not unusual. For the band to feel they needed a sub textual specific sound with a complementary visual discourse not only skirted away from the ethic of the work, but obliterated a positive projection of what it is to center one’s life in Christianity. Faith-based music is not only personal, it also reaches an audience. “Jesus Freak,” I argue, claims a self-indulgent sounding rhetoric for a band teetering on the brink of either a hiatus or disbandment. The visual elements supply the necessary critical reading of this work to dismantle the troubling layers to obtain the response – rhetorical or vocal – from the band and their need to qualify the inverted pop cultural derogatory phrase “Jesus Freak.”

Visual Discourse, DC Talk

Attention has been given to the sounding history of DC Talk. There visual works have been given little critique. The visual appeal and emphasized discourse in the works of DC Talk demands a critical review to capture the full breadth of their work, in particular at the stunning transitional moment for the band in the mid 1990s. Attention to the visual representations will underscore how the band evolved from their Hip Hop/pop sonic roots to relate to and speak with (for?) a younger faith-based/Christian audience.

The visual references in DC Talk’s “Jesus Freak” portrays a stark demeanor. The video positions the band in an environment constructed to heighten the sounding narrative of their work. Directed by Simon Maxwell, the visuals are riveting by their own accord. To ascertain a sub textual apologetic voice – if one is present – this work brings forth the necessity for a critical reading of the visuals, band association with the included elements, and the space-place of the video.

Arriving in the mid 1990s, “Jesus Freak” contrasts earlier works without a an eloquent bookend to the bands recording history. Rather, this work,, when read visually, illustrates and underscore how Christianity is and can be viewed by those founded in this faith-based music genre. Placing a once Hip Hop(-ish) band against their own self-proclaimed intent of the video, lyrics, and sonic context, recognizes the varying difference in their sound and accompanied artistic critique of how they elected to visually portray Christianity. To profile a posture of being a sonic apologist or a secular, bowing-to-culture vernacular misses the mark on the visual realities and narrative DC Talk presents.

DC Talk, Jesus Freak (1995) – Jesus Freak

The video opens with a descending white dove. The dove – a proverbial symbol of the Holy Spirit as noted in scripture (Matthew 3:16; Mark 1:10; Luke 3:22; John 1:32) – flies in what appears an open space. A closer view shows the dove being projected on two black screens with a single white light shining from illuminating the image. Here, the text presents a controlled display of a Christian symbol, the white dove as the Holy Spirit. This underscores a manufactured position of a socio-religious appropriation.

The video cuts to DC Talk members in either a chapel or a prison. The metaphor here is that they are captive in a limited space, bound due to the open proclamation of Jesus being the Savior (Acts 16:16-40; Acts 12:5-17). The slight visual of the prison bars qualifies that the chapel itself is the prison. A cross is branded, silver coins are dropped, black and white flags from different “Christian countries,” and further black and white images of impoverished children unfold. The image settles on the band, in (living) color in the chapel-prison. The black and white juxtaposed with the full color images of the band rings codifies a historical narrative, past against present. The historic images narrate different times in global history where people, women and children, mainly, with contrasting male representations of power (ex., Haile Selassie I) are modeled. There are minimal references to men under socio-religious persecution. Those images are static while other historic – and contemporary male images (read: the band members themselves) – exist in motion and with a longer access to time-space in the video. Later, images of burning books (it is assumed that these are bibles being burned as in the 1930s Germany where religious texts were burned), women working in the fields, children playing under a silhouette image of a cross, and excerpts from religious art speak from a voice of oppression toward Christianity that remains historic. The closest that the (living colored) band comes to this context is the objectified use of a wooden cross.

The prisoner photos of two band members wearing the marker, “FREAK” attempts to align the contemporary with the historic using the black and white signifier as before. This well-placed image arrives much too late in the video’s narrative. The placement does little in the way of trouping the forward thrust visual amplification that the band is objectifying Christian oppression as a historic relic and their relevant contemporary position as a living semiotic of a market authentic “christian” doctrine. The self-identified ideological qualifier, the “FREAK” maker, captures the moment in space-time where the band members articulate an assumed authentic identity, the argument of being a “Jesus Freak.” This action is the closest we visually obtain of the band seeking to align themselves with the derogatory venom of the phrase “Jesus Freak.” However, the band is not completed positioned in black and white. The adapted colored highlights of the image protect the band from the necessity to revise their objectified narrative of historic Christian persecution. Though a valiant sub textual gesture, absent of the historic black and white context, the band remains apart from the visual levels of oppression demonstrated. The “Jesus Freak” marker ideologically functions to isolate the band from the negative context of the phrase while portraying the appearance of appropriation of living persecution.

Visually scripted, “Jesus Freak” is marketed for a consumer secular attitude while remaining in posture for their established faith-based audience. This border-crossing agenda, visually, is devoid of such a socio-religious dialogue. There is an artistic dialectic in play where the band contextualizes their position as authority (read: lyrics, colored images, breaking of break, (mis)handling of a wooden cross, et al., against the historic energy of religious/faith-based oppression and persecution.

The floating images against the consistent double screen projection draws attention. “Faith,” Truth,” and “Angel” are seen in the first wave of texts. The second set of text to pass state “Hope” which is further attached to “Hopeless.” Reading this term, following the use of the black and white images, then, we see that hope in faith, truth and angelic (read: scripture/biblical truth) is hopeless in history and completely absent in the modern setting. These words only appear in black and white, never in color. Later, the words, “Deluge” (delusional) and “False Prophet” are presented, in a brief rapid-fire passing. This is the closest point in the video where DC Talk attempts to present a visual reference to historic accusations of Christ being a false prophet ( Matthew 24; Mark 13; Luke 21).

The performance postures, position, and movements throughout the video weave a tapestry of period-centered seduction and toward the end of the video question an erotic coupling with two of the male members leaning chest-to-chest. The use of stoic images display a position of confidence and dominance. These trivial moments are juxtaposed by their hyper-gyrations later in the video during the simple highly produced guitar solo. Extending these pop culture acrobatics, the band centers their attention on the camera – a gaze toward the reified “other” – as they objectify themselves as a spectacle. Their sultry strides toward the camera in disordered ranks contrast with static postures. Such visually appealing poses do little to enhance the content of their message. Rather, these movements throughout the video’s limited space underscores the band’s desire to market their work and update their appeal to a younger time and cultural norm. The melodramatic bravado of these motions illustrate the band’s desire to prioritize their current position and power of the text, the video. Layering these counter-cultural sexually infused movements from an all male band, amplified in color, reads their prominent colonization of socio-religious meaning. The dynamic contrast of the contemporary color against the historic black and white images through subconsciously narrate colonial authority. The territory of religious doctrine, history, and present-day relevance is the colonized matter.

The on-screen projected black and white images start the video and increase in presentation as the song progresses. The succession of these historic images does not invert or script a post-colonial dialectic. Thee increased frequency of these historic images succumbs to the sharp flashes of (blue) light over the band. The choice of the color blue magnifies a sense of life, and, ironically, a nature of calm. The heightened tension associated with the color blue, in this case, promotes a military ethic and control over the black and white images. The more frequent the historic images are shown – and their length of time as well – the sharper the contrast and extended time the color blue is incorporated.

As the video begins to close, the label “FOR COLORED ONLY” appears, first in the subdominant background and later in a profile position. The obvious use is to reference America’s racist history of segregation (1900 – 1939). The projection collects the precursor images of cathedrals on fire, police brutality, holocaust incarceration, slavery, and wartime demise. A simple frame positioned at a dramatic point in the video, while the lyrics revolve around the binary theme of the track, “What will people think/when they find out I’m a Jesus Freak [?]; What will people do/when they find out it’s true [?]”. If we gesture to answer these questions, following the provided video narrative thus far, it can be qualified that being a “Jesus Freak” is littered with colonial oppression, segregation, and a lexicon of violence. A contemporary non-faith-based viewer could, then, aptly assume that to be such a “Freak” is not worth the investment of time, religious practice, nor required doctrine discipline. Ironically, the label “FOR COLORED ONLY” references segregation and throughout the video the band is in color. Following this logic, is the band – assuming their argument of being a “Jesus Freak” – then pointing toward a separatist agenda dividing history from contemporary, faith-based from non-faith-based, Christian from non-Christian? Is it not a the apologetic discipline of a disciple to argue for the cause and support Christianity? Is it not a core tenant of the gospel to make disciples (ex., Matthew 28: 19 -20)? “FOR COLORED ONLY” reads as another unclear and indecisive signifier used in the video absent of a negotiation to support Christianity. This signifier objectifies a semiotic binary supported non-verbally by the band’s presence in the video in color. They are marginalizing themselves (read: as “Jesus Freaks”) away from an operation of supporting and arguing for discipleship. To be in “Color,” then, is a liminal existence afforded to only a privileged, selected few. In sum total, the band speaks a contradiction of image and lyrics defeating the assumed purpose of this track, to support a “decent Christian” ethic for faith-based and non-Christians.

Toward the end of the video, the black and white backdrop against the colored presentation of the band slices through as does the guitar solo. In the background the Russian hammer and sickle is seen as a shadow with the word, “Conform” lined atop. A flash of a moment, this could be subconsciously assumed as “Communism.” The artistic gestures – which must be qualified as approved by the band since this is the official video for the release – does more psychological disturbance than help the case of winning individuals to reconcile the core content of the work, being a “Jesus Freak” is a positive posture.

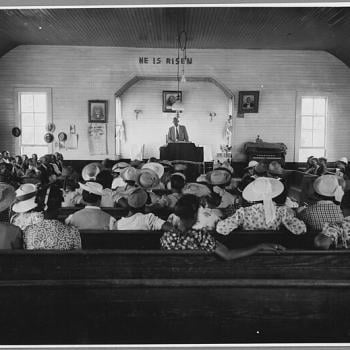

Following this are images of the 1957 Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), largely attended by African-Americans at this time for the rise and support of Christianity in the troubled racist south. A few seconds later, the before secluded hammer and sickle is clearly visible waving adjacent a church steeple. Such visuals may be artistically stunning and attention grabbing for a non-faith-based viewer. For a knowledgeable faith-based viewer this narration poses strong socio-religious complications.

Multiple images display martyrs and open desecration of Christianity. The use of a wooden cross as a semiotic token toward faith proves disturbing. A self-labeled group “Decent Christian” Talk is an assumed preface to positive representations of Christianity. If one is not a follower of Christian faith and values this video draws controversy through the conflicted use of language/text and images. Such an audience viewer may forward the question, “What is a ‘Jesus Freak?'” or, even more to the point, “Do I want to be a ‘Jesus Freak?'”

But, Do You Really Care?

Bringing this point to a close, the opening black and white visuals project the words, “ALL OF US TOGETHER.” On cue, the word “MAN” appears above “TOGETHER.” As “TOGETHER” fades, “MAN” is left lingering high above the various country flags waving. The following phrase, “ONE FAMILY” is separate from “MAN” as that term hangs high above. The point attempts to illustrate that “man is one family” aside form real or constructed borders. the attempt is minimized as “MAN” continued to be in the dominant position above “TOGETHER” and “ONE FAMILY.” Further, “MAN” is transposed on top of “TOGETHER” demonstrating an even stronger power position of man. As “ONE FAMILY” peaks from the lower portion of the textbox, the division between these two words – “MAN” and “ONE FAMILY” – phenomenologically and psychologically points to a male-centric position of power. The viewer is reminded of the use of the male dominance throughout the video in black and white historic images (Halie Selassie I) and in color (the band members themselves).

These collaborative image narratives and textual discourse at the start of the video presents a complete bookend to the video. Throughout, the band escalated their visual references, codified with distorted lyrics that flirt with scripture and man-made nuance. The repeated rhetorical question, “What will people think/When they find out I’m a Jesus Freak [?]” leads to the second unanswered question, “What will people do/When they find out its true [?]”. Taking the opening visual script with these repeated questions, DC Talk does not disengage a physical reference to their self-proclaimed intent for the song to win over unbelievers. Rather, the profile – “MAN” – combined with these rhetorical questions bind together a selfish posture, a rationalistic modernist narrative that contextualizes a personal desire to pose the rational as real. These combined images narrate a pseudo-Hegalian reading promoting man’s superiority steaming from his rational mind. “Know thyself” – a true Hegalian philosophy framed by a discourse of immanence founded by one’s own internal criteria. DC Talk qualifies man’s immanence through the interlocking of words/language, visual appropriation, and their location in the video. There is a desire to almost leave the rhetorical questions of the lyrics-visuals unanswered.

DC Talk responds to this binary by way of a repeated denial. This operates less than a solid affirmation of faith and more as a lethargic and undesired attempt to correct the ill nature of the images and lyrics. “I don’t really care” is the final statement by DC Talk, echoed in a vacuum. Functioning as a period to the lyrics and a stop to the visuals, DC Talk speaks clearly that they really “don’t care.”