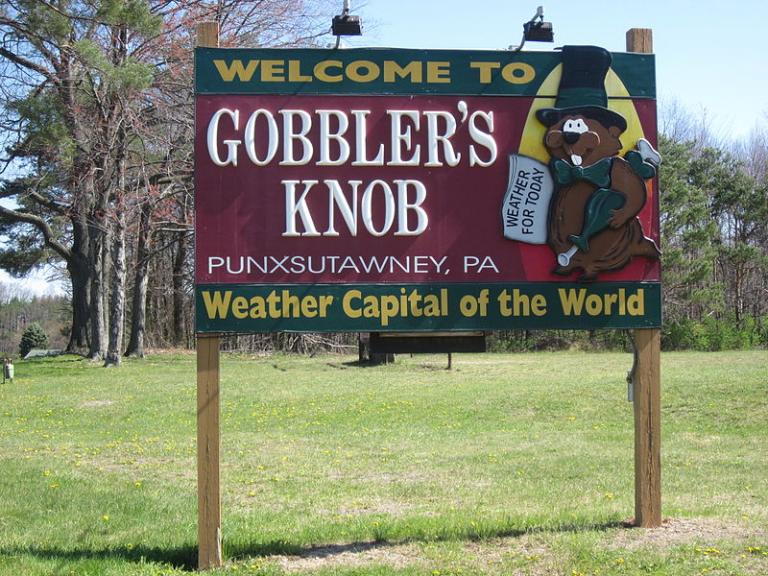

Every year on February 2, news channels across the country broadcast from Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania (fun fact: I was born here) where Groundhog Phil emerges from his burrow to look for his shadow. While many people are only aware of this tradition because of the 1993 Groundhog Day starring Bill Murray, there’s actually a lot more to this holiday than meets the eye. Its origins are quite old in fact and lie within the weather divination practices of our ancient pagan ancestors.

The legend of Groundhog Day is summed up well by this description from the American Philosophical Society in 1888. It states: “If the groundhog sees his shadow on the second of February, he goes back to his hole in the ground for another six weeks’ doze, as he knows that the winter will endure so much longer; per contra, if he cannot see it, he stays out, for he knows that the severe weather is past.”

Belief in the ability of animals to predict the weather is common in many different cultures and is often associated with specific times of the year, in the case of Groundhog Day-Candlemass or Imbolc. “In these superstitions, there is the implicit assumption that plants and animals are somehow in tune with the cosmic forces which determine the weather and that they behave in harmony with these forces.” (Ward, 1968)

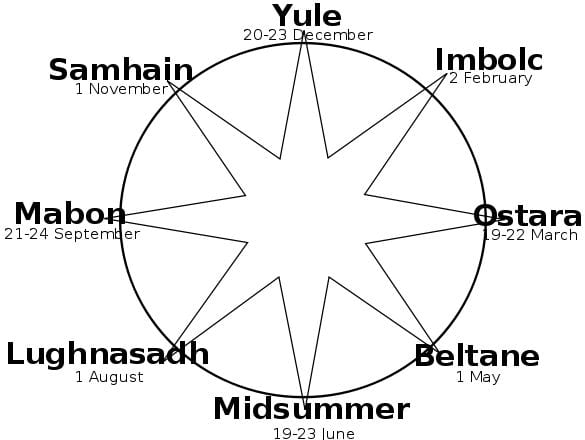

Groundhog Day falls onto the cross-quarter day commonly known as Imbolc or Candlemas. These cross-quarter days (meaning midway between the solstice and equinox) were traditionally times for divination because it was believed that the ‘veil between the worlds’ was thinnest during these periods, thus making divination easier.

“Sign superstitions regarding weather are known to all, the most famous being the groundhog oracle which provides that if the groundhog sees his shadow on the second of February (which, in the church calendar, is Candlemass) there will be six more weeks of winter.” (Western Folklore, 1954)

Several folk proverbs from around Europe speak to this tradition:

From England:

“If Candlemas be fair and bright,

Winter has another flight.

If Candlemas brings clouds and rain,

Winter will not come again.”

From Scotland:

“If Candlemas Day is bright and clear,

There’ll be two winters in the year.”

From Germany:

“The badger peeps out his hole on Candlemas Day, and, if he finds snow, walks abroad; but if he sees the sun shining he draws back into his hole.”

When the Pennsylvania Dutch emigrated to the United States in the 19th century, they brought with them their folk customs including those associated with Candlemas. As there are few badger east of the Mississippi River, the role of weather prophet was transferred to the groundhog.

We see the first written reference to this tradition in the diary of a Pennsylvania storekeeper from 1841.

“Last Tuesday, the 2nd, was Candlemas day, the day on which, according to the Germans, the Groundhog peeps out of his winter quarters and if he sees his shadow he pops back for another six weeks nap, but if the day be cloudy he remains out, as the weather is to be moderate.” –James Morris (February 4, 1841)

In 1886, Pennsylvania’s official celebration of the holiday began and Punxsutawney Phil was given the official title

‘Seer of Seers, Sage of Sages, Prognosticator of Prognosticators, and Weather Prophet Extraordinary’

I love the tradition of Groundhog Day. We live in a world where information is at our fingertips. Weather is predictable weeks in advance thanks to technological advancements. The world is disenchanted. For me, Groundhog Phil brings a little of the enchantment back. Here are a few ways you can celebrate:

- Tune in to the festivities live in Gobbler’s Knob, PA here: Groundhog Day Live Stream

- Do a little bit of your own research and find out if any of the local wildlife have weather predicting traits! Go for a walk on the morning of February 2 and keep an eye for animals. Who knows what you might find out?!

- If you’re within driving distance of Punxsutawney, why not head down for the day?

References:

“Groundhog in Dog’s Shadow.” Western Folklore 13, no. 2/3 (1954): 209.

“Groundhog Tradition Attacked.” Western Folklore 10, no. 3 (1951): 252.

Phillips, Henry. “First Contribution to the Folk-Lore of Philadelphia and Its Vicinity.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 25, no. 128 (1888): 159-70.

Randloph, Vance; Ozark Superstitions.

Ward, Donald J. “Weather Signs and Weather Magic: Some Ideas on Causality in Popular Belief.” Pacific Coast Philology 3 (1968): 67-72.