The Holy Bible presents the reader with a single, definable, consistent deity who speaks with one voice throughout the entire Bible. That much we know. Right?

Does the Bible speak of gods other than Adonai?

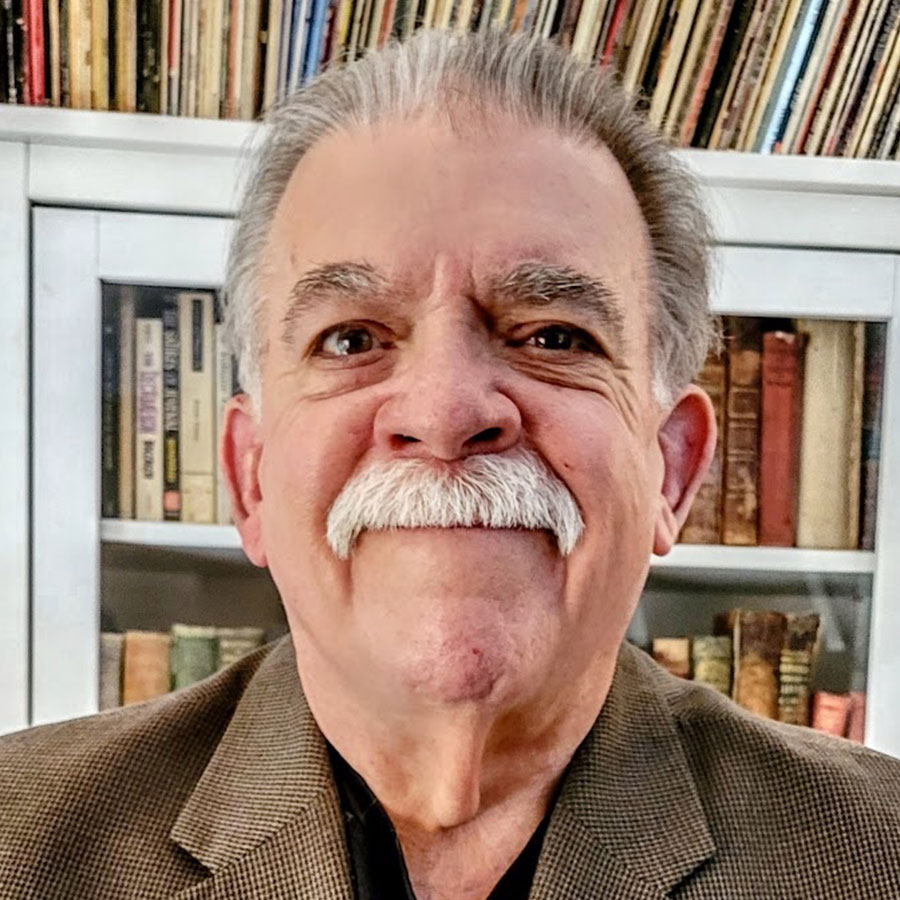

Author’s note: I am using the substitute for the Tetragrammaton and non-binary pronouns when describing the god of Israel and of Christianity.

Anyone who has attended church regularly or who went to Sunday school as child has certainly learned that the Bible teaches us that the God of Israel and the God of Jesus and his disciples is the only deity that exists and that deserves consideration within the pages of the Holy Bible.

I can remember in my own upbringing that I was clearly taught that there was one God for the universe, that his dominion encompasses all things, and that there is no other deity or power with whom we need to be concerned.

This teaching has been enforced throughout Western civilization’s history and when people question whether or not there could be additional deities written about in the Bible they have at times, been branded as heretics or apostates.

The Bible not only speaks of additional deities, but it is also true that the deity worshipped by Jews and Christians, in some passages in the Bible, recognizes, interacts and even does battle with other deities.

These facts are not hidden within the pages of the Bible but are clearly available to the reader if they choose to read the Bible for everything it contains and not just a source of agreement with their preconceived beliefs and ideas. The reader, in reading with an open mind, will readily discover that there are many additional deities spoken about in the Bible and that these deities interact not only with Adonai but with the people that the Bible is written about and the people by whom the Bible was written.

Where does the Bible speak of other deities?

In the first sentence of the first chapter of the Book of Genesis, the author wrote:

“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.”

This has also been translated:

“In the beginning, when God created the heavens and the earth,”

but that difference is not what we are concerned with at present.

In Hebrew, the English transliteration would be:

The author here uses the word “elohim” to refer to the deity who creates the heavens and the Earth. “Elohim” is a plural word in Hebrew, meaning gods.

Scholars agree, however, that the use of the word “elohim” here is a singular usage. This same text source also uses the Tetragrammaton (for which we are substituting

“Adonai” in accordance with custom) to refer to this same deity.

In verse 26 of this chapter, Adonai creates humans.

26 And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.

27 So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.

Reading from the King James version of the Bible, we can see that the author does not present Adonai here as entirely male and entirely singular.

According to this Genesis author, this concept of Adonai can be interpreted in more than one way. Obviously, the author is using the masculine singular but he also uses the first person plural and makes these created humans both male and female and both in his image.

In this first book of the Bible, God is depicted both as male and as non-binary, as a singular deity as well as plural deities.

Those who insist that the Bible depicts only one singular, male deity are simply denying what the text clearly shows.

Why do we try to identify the deities in the Bible?

The Bible has come down to us through a series of events, some deliberate and some a reaction to outside forces. It has been presented and accepted as the necessary and sufficient guide to the faith and practice of Jews and Christians for many generations.

If the Bible spoke with a single voice, from a single viewpoint, its study and scholarly inquiry would be less useful than it currently is. There would be little need for interpretation. It would all be black or white, red or blue, cold or hot, big or small.

We know that the Bible’s books do not speak with one voice, were not written by a single author, do not describe events in the same way, do not, and this is important to grasp, espouse the same theology. The books do, however, speak of multiple deities, even if one particular deity is seen as the most important and for some, the only deity in existence.

How can we begin to understand this question of multiple deities?

In order to gain an understanding of how the Bible can speak of many deities, we need to establish the context, place and time of the writing of these books over several hundred years.

Before it is anything else, the Bible is the story of the ancient history of the Jewish People. I use a capital P because the Peoplehood of the children of Israel is in reality what the Hebrew Bible is about. The New Testament is about a tragedy, a triumph and a change in the theology of some of these Jews which became a new religion of both Jews and Gentiles.

What is the historic background of the Hebrew Bible?

The Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) purports to trace the beginnings of the world and the wider universe and the first covenant the God of Israel made with their people.

Unless we are “young earth creationists,” we know that the creation stories in Genesis are simply myths and fables.

Following this idea, we also can see that the Biblical accounts of a world-wide flood brought by God to cleanse the Earth of his bad creations is not only mythical, but also quite similar to a much older flood myth.

This myth, the Epic of Gilgamesh tells of a flood brought by gods, reacting to misbehavior by humans, and allowing one man and his family to survive to re-populate the Earth after the flood. This account, varying somewhat in Akkadian and Babylonian mythology, is a precursor to the flood myth in Genesis, which involves a single deity the God of Israel.

The Bible authors are clear in describing the flood myth that there is only one god (or at least, only one god about whom we need to be concerned).

What does the Genesis flood myth have to do with the number of gods in the Bible?

Sadly, almost nothing in the Bible is straightforward. That is evident here. In its lead up to the flood stories, the Genesis author introduces new beings whom the reader has not yet encountered.

We read:

6 When man began to multiply on the face of the land and daughters were born to them, 2 the sons of God saw that the daughters of man were attractive. And they took as their wives any they chose. 3 Then the Lord said, “My Spirit shall not abide in[e] man forever, for he is flesh: his days shall be 120 years.” 4 The Nephilim[f] were on the earth in those days, and also afterward, when the sons of God came in to the daughters of man and they bore children to them. These were the mighty men who were of old, the men of renown.

5 The Lord saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every intention of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually. 6 And the Lord regretted that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart. 7 So the Lord said, “I will blot out man whom I have created from the face of the land, man and animals and creeping things and birds of the heavens, for I am sorry that I have made them.”

We do not have to do a lot of interpreting here to see that the author is describing beings who are not fully human, who are the genetic offspring of the “Sons of God,” a class of beings not otherwise described here, but whose name will recur later in the Hebrew Bible.

These beings are not “gods” but the offspring of “sons of God,” “mighty men of old,” “men of renown.”

These Nephilim are not human and not Gods. The Bible gives no further elucidation, but gives the reader pause. What could this mean?

It is interesting to note that while the canonical books of the modern Bible do not contain a further explanation regarding these Nephilim, there were books in circulation in ancient Israel that described the exploits of another Biblical character, a man named named Enoch.

In Genesis, Chapter 5, Enoch was “taken by God” and the Biblical authors elude later to Enoch but the Bible’s books tell little else about him.

The non-canonical (but popular in their day) books are First, Second and Third Books of Enoch.

We are straying here from the text of the Bible, but the background of ancient Israel is incomplete without knowledge of the Books of Enoch.

The Books of Enoch relate a narrative in which heavenly beings (not described as deities, exactly) or possibly angels interact and conflict.

After the flood, what deities do we find in the Bible?

The flood marks a turning point. Adonai promises Noah that they will not drown the world again, but the introduction of the “sons of God” and the Nephilim are not explained.

The people, following the flood, continue to do things that infuriate Adonai. They build a tower trying to reach heaven. Adonai confuses their language.

Later in the Book of Genesis, in chapter 35, is the story of Jacob burying “foreign gods’ under a tree.

We learn that Jacob has been instructed by Adonai to lead his family and his retinue to Beth-El and build an altar.

Jacob tells his family to:

“Get rid of the foreign gods you have with you, and purify yourselves and change your clothes. 3 Then come, let us go up to Bethel, where I will build an altar to God, who answered me in the day of my distress and who has been with me wherever I have gone.” 4 So they gave Jacob all the foreign gods they had and the rings in their ears, and Jacob buried them under the oak at Shechem.

Since Jacob can bury these gods, we clearly see these as idols, not necessarily as living gods, but we cannot ignore that the people of Adonai, in this period) recognized and worshipped other gods besides Adonai.

(Jacob’s altar at Beth-El much later becomes the site of Israel King Jeroboam’s shrine of the golden calf, which relates back to the Moses/Aaron story in the Book of Exodus. “Here are your gods, Israel.”)

28 After seeking advice, the king made two golden calves. He said to the people, “It is too much for you to go up to Jerusalem. Here are your gods, Israel, who brought you up out of Egypt.” (1 Kings 12:28 NIV)

This language matches the language attributed to Aaron when he makes the Golden Calf in the wilderness. (Exodus 32: 1-3 NIV)

1 When the people saw that Moses was so long in coming down from the mountain, they gathered around Aaron and said, “Come, make us gods who will go before us. As for this fellow Moses who brought us up out of Egypt, we don’t know what has happened to him.”

2 Aaron answered them, “Take off the gold earrings that your wives, your sons and your daughters are wearing, and bring them to me.” 3 So all the people took off their earrings and brought them to Aaron. 4 He took what they handed him and made it into an idol cast in the shape of a calf, fashioning it with a tool. Then they said, “These are your gods, Israel, who brought you up out of Egypt.”

Other gods in Egypt

Following the Abraham, Isaac and Jacob stories, we find the people in Egypt, where they have gone anciently to avoid famine. They are treated badly in Egypt and Adonai commissions Moses, a Hebrew who has been raised in the Egyptian court and has been forced to leave Egypt, to go to back Egypt (he is in exile in Midian) and free the people from Pharaoh.

Moses returns to Egypt and begins a series of negotiations with Pharaoh to entice him to let the people go.

These negotiations culminate in a competition between Moses and Pharaoh’s magicians to determine whose gods are stronger. Adonai wins the contest but Pharaoh still does not free the people.

Adonai then produces plagues on the Egyptian people to defeat Egypt’s gods.

The final plague, death to the first-born, finally seals the victory for YHWH and their people.

After Egypt, then what?

Following their escape from Egypt, the people, led by Moses, wander in the desert for 40 years on their way to the land of Canaan.

The people abandon Adonai in the wilderness and begin to worship other gods:

11 Then the Israelites did evil in the eyes of the Lord and served the Baals. 12 They forsook the Lord, the God of their ancestors, who had brought them out of Egypt. They followed and worshiped various gods of the peoples around them. They aroused the Lord’s anger 13 because they forsook him and served Baal and the Ashtoreths.

The people, in this period, have begun to worship the gods of the people around them, the gods of the Canaanites.

What gods did the people worship in Canaan?

The first two Canaanite gods we encounter in this period are Ba’al and Asherah (recognize alternative spellings in ancient texts). we need to consider these important gods in the Canaanite pantheon.

Ba’al

Ba’al was a storm god of the ancient Canaanites. The language of his descriptions is very similar to the language used to describe Adonai in some of the Psalms. In fact, it is easy to confuse the descriptions of Ba’al with the descriptions of Adonai.

In the text of Psalm 29, (ESV) we find the verses:

1 Ascribe to the Lord, O heavenly beings,

ascribe to the Lord glory and strength.

2 Ascribe to the Lord the glory due his name;

worship the Lord in the splendor of holiness.

Then notes to this section indicate that a close translation of the Hebrew, instead of “heavenly beings,” the translation should be “sons of God” or “sons of might.” This language is reminiscent of the language of Genesis 6 as we have seen.

These creatures are not described as deities, but they dwell in the heavenly realm and they are not human.

Asherah

In the most ancient Canaanite and Ugaritic texts and legends, Asherah is the consort to the high god El and in some texts to the god Ba’al. She is a fertility goddess and the goddess of childbirth and of mothers. Her roles in the mythologies are not exactly congruent in texts covering a period of more than 1000 years.

As we have seen, Asherah first appears in the Bible in the period of the judges. This period is thought to be about 1150 BCE to about 1000 BCE. The lack of historical records makes these early dates somewhat fluid.

What is interesting is that Asherah’s shrines were found in the Jerusalem temple to Adonai as late as the time of King Josiah (640 – 608 BCE): (2Kings 23: 4-6 NIV)

4 The king ordered Hilkiah the high priest, the priests next in rank and the doorkeepers to remove from the temple of the Lord all the articles made for Baal and Asherah and all the starry hosts. He burned them outside Jerusalem in the fields of the Kidron Valley and took the ashes to Bethel. 5 He did away with the idolatrous priests appointed by the kings of Judah to burn incense on the high places of the towns of Judah and on those around Jerusalem—those who burned incense to Baal, to the sun and moon, to the constellations and to all the starry hosts. 6 He took the Asherah pole from the temple of the Lord to the Kidron Valley outside Jerusalem and burned it there. He ground it to powder and scattered the dust over the graves of the common people. 7 He also tore down the quarters of the male shrine prostitutes that were in the temple of the Lord, the quarters where women did weaving for Asherah.

We can see from the text of the Bible itself, references to a goddess in the Jerusalem temple, being worshipped there by the people, along with th Canaanite god Ba’al.

These descriptions of worship by the people of Adonai in the Jerusalem temple. A similar event had occurred before during the reign of reformer king Hezekiah (716-687 BCE)

In the third year of Hoshea son of Elah king of Israel, Hezekiah son of Ahaz king of Judah began to reign. 2 He was twenty-five years old when he became king, and he reigned in Jerusalem twenty-nine years. His mother’s name was Abijah daughter of Zechariah. 3 He did what was right in the eyes of the Lord, just as his father David had done. 4 He removed the high places, smashed the sacred stones and cut down the Asherah poles. He broke into pieces the bronze snake Moses had made, for up to that time the Israelites had been burning incense to it. It was called Nehushtan.

Author’s note: We need to reflect here. Since the Exodus from Egypt, before the judges, before the first king, the Bible tells us that there is but one god, Adonai, that they are the creator and the liberator of the people from Egyptian bondage. Yet, every time a king of Israel or Judah begins a reform campaign, among the people of Adonai, the king finds idols of foreign gods and especially idols to and worship of Ba’al and Asherah, the enemy to Adonai and the consort of that enemy or to Adonai themselves.

It appears that the people of Adonai, from the time wandering in the wilderness (c 1200-1000 BCE) at least to the last days of Judah (586 BCE) and probably into the second temple period, (538 BCE – 70 CE) were worshipping many gods in their homes and even in the Jerusalem temple.

They certainly did not teach that in Sunday School.

Chemosh

Chemosh was a Moabite god. Moab was a neighboring state to Israel. Even King Solomon, seen in the Biblical narrative as a paragon of virtue is led astray by foreign wives. (1 Kings 11: 1-8 NIV)

11 King Solomon, however, loved many foreign women besides Pharaoh’s daughter—Moabites, Ammonites, Edomites, Sidonians and Hittites. 2 They were from nations about which the Lord had told the Israelites, “You must not intermarry with them, because they will surely turn your hearts after their gods.” Nevertheless, Solomon held fast to them in love. 3 He had seven hundred wives of royal birth and three hundred concubines, and his wives led him astray. 4 As Solomon grew old, his wives turned his heart after other gods, and his heart was not fully devoted to the Lord his God, as the heart of David his father had been. 5 He followed Ashtoreth the goddess of the Sidonians, and Molek the detestable god of the Ammonites. 6 So Solomon did evil in the eyes of the Lord; he did not follow the Lord completely, as David his father had done.

7 On a hill east of Jerusalem, Solomon built a high place for Chemosh the detestable god of Moab, and for Molek the detestable god of the Ammonites. 8 He did the same for all his foreign wives, who burned incense and offered sacrifices to their gods.

The Biblical author says that Solomon, the last king of a united Israel, built shrines to gods other than Adonai, in direct violation of the Mosaic commandment.

The next mention of the Moabite god Chemosh is in the book of 2 Kings. In this passage, king Jehoram of Israel (divided) is doing battle with his neighbor, the king of Moab. The Israelites are not doing well against the Moabites and Adonai assists the Israelites.

When the battle begins to go against Moab, its king sacrifices his oldest son on the walls of the city.

This act apparently was too much for the Israelites, who leave and go home.

Chemosh has seemingly defeated Adonai.

This is the only place in the Hebrew Bible where the author indicates that a foreign god has defeated Adonai.

Are there additional gods mentioned in the Bible?

There are mentions of several other gods and heavenly beings in the Bible. These discussions are less consequential to the main stories than the gods we have explored so far. An article by Gerald McDermott discusses these min more detail.

Where do we go from here?

We have seen that the Bible does, indeed, speak of gods other than Adonai. The Biblical authors are clear throughout the Bible that the people of Adonai (and this will later extend to the whole world) must worship Adonai and Adonai only. It is difficult to see which authors accepted Adonai only and which might have accepted other deities. The original intentions of the Bible authors have been filtered through 2000 years of theological interpretation.

In our next article, we will explore Psalm 82 and the idea of the Council of Heaven.

There are many controversial ideas in this article. I would be grateful for comments from readers. I am a public student of Biblical scholarship and I am trying to learn as much as I can. Please join me on this quest.