What is a witch? Today this question has loaded implications for many of us, some of them sociopolitical. Traditionally, the word was used to describe someone who used supernatural powers to affect change, a person who was seen as an outsider to “normal” society – someone who thought, and lived, differently from the others. Today many of us proudly celebrate our identities as witches as we define the word for ourselves, taking it back from the stigma of evil long associated with it, thereby casting a powerful spell on the culture, manifesting change.

The association between women and witchcraft is ancient and deep-rooted in Western culture. There are many examples of witchcraft empowering women in mythology and folklore, some for evil purposes, and some for good. Although characters are not real people, they can have a powerful effect on the shaping of our ideas and attitudes. Perhaps this is why it can be frightening for some people to see a woman step out of a submissive role… in a conversation, or in a hierarchy. When she does so, she is breaking away from social norms that were shaped long ago, disrupting a social order that was put in place in Europe and followed whites to the “new world” of America. Empowered with a will of her own, she lights up the witch archetype deep in the unconscious, where fear looms over reason.

Though you would be hard-pressed to find someone today who would openly admit to feeling afraid when the social order is disrupted, the disproportionately low representation of women in leadership positions is just one example of evidence that there is a disparity between what we preach and what we practice. Obviously, our society faces challenges in moving beyond institutions of oppression. In order to challenge laws and norms that are unjust, one must have the courage to go against the grain of society. This is often necessary in order for policies to change and cultures to evolve.

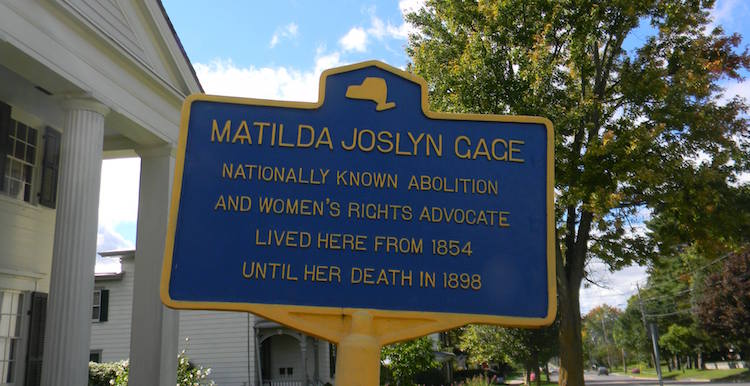

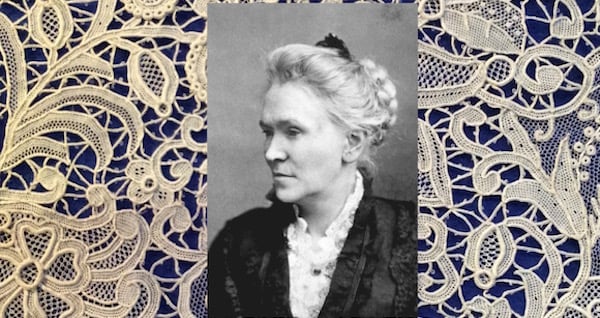

In the mid-1800s, a small group of individuals in upstate NY had been thinking about the American ideal of freedom, and they made an important decision. They chose to form a movement that would bravely confront the inevitable social and legal battles that would result from living by principles that they knew were right, even though not yet socially accepted or legal. Though they lived without rights and privileges that we now take for granted, they were passionate in their pursuit of a better America, and they worked tirelessly for social reform. One of them was Matilda Joslyn Gage. The daughter of a doctor, Gage was a woman of relative privilege. Against the enslavement and indignation of all humanity, she was an abolitionist, a second-generation participant in the Underground Railroad.

Her work as a suffragist and civil rights advocate was part of a broader perspective she held, informed by her study of history, anthropology, culture, and comparative religion. She began her involvement in the National Woman Suffrage Association by spreading the word of their events and messages through publications for which she wrote. Shortly after she became a leader of the movement, contributing important work, alongside such revolutionaries as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frederick Douglass, Lucretia Mott, and Susan B. Anthony.

In Gage’s time (March 24, 1826 – March 18, 1898), women were not allowed to own property; rather, they were themselves considered the property of men. Marriage was an institution of man’s ownership of woman. Men had the legal right to beat their wives, and they were socially encouraged to do so. Although expected to mother and care for children, women had no legal rights to their own children, and they could lose custody of them at the whim of their husbands. Where did this oppressive system come from?

In her book, Woman, Church and State (1893), Gage wrote extensively about the politicization of a particularly misogynistic strain of Christian ideology used as a governmental tool of social control, and normalizing the idea that women were inherently evil. This ideology focused on the concept of original sin, teaching that life comes from Eve, who brought sex into the world by way of disobedience; sex is unclean and against the wishes of God; man lowers himself to unite with woman through sex, thereby distancing himself from spiritual aspirations. As daughters of Eve, women are to blame for the fall of humankind from the Garden of Eden. Woman cannot be trusted and should be dominated and controlled rather than loved as an equal, her pain and her blood a curse, rather than a gift. As Gage saw it, the view of woman through this lens planted the seeds of an unhealthy culture, a society at war with woman, sex, nature, and family… affecting laws, policies, and daily life in the nineteenth century.

The idea of the witch, and its effect on women, was something to which Gage had given much contemplation. A book discussed in her work, as a tragically powerful influence on the culture,was the Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of the Witches), (1487). The book implies that witches have the power to emasculate men, and they do so by congregating with the devil. Gage wrote about how the book associated womanhood with witchcraft, thereby painting women as evil, inhuman, and unworthy of empathy. She believed this affected the brutal treatment of women in witch trials, and continued to have a lasting effect on European culture and the American culture in which she lived. This was an important observation, and also an influence on twentieth century Wiccan and feminist thought. Gage wrote: “Although witchcraft was treated as a crime against the state, it was regarded as a greater sin against heaven, the bible having set its seal of disapproval in the injunction ‘Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.’ The church therefore claimed its control.” (Gage, 1893) She pointed out that social acceptability of the torture and murder of women, theologically inspired, is one example of injustice resulting from state enforcement of religious ideas, underscoring the importance of separation of church and state.

In the chapter of Gage’s book titled Celibacy, she gave an example of how ancient misogyny continued to be alive and well in her times: “As late as the Woman’s Rights Convention in Philadelphia, 1854, an objector in the audience cried out: ‘Let women first prove they have souls; both the Church and the State deny it.’” (Gage, 1893) Woman’s struggle for equal rights, and the opposition aimed at her for trying to break out of the role socially enforced upon her, resulted from ideas about women being innately inferior and unworthy – holdovers from the scriptural demonization of Eve. The anti-suffrage movement exhibited their obvious fear… fear of role reversals between women and men, fear that women’s liberation would equate with men’s bondage, and that men would have to take on a nurturing role if women entered arenas traditionally reserved for men. There are many examples of anti-suffrage materials demonizing suffragists, depicting them as ugly and neglectful of their homes and families, unattractive in the eyes of men, or reduced to sex objects as they tried to be counted as equals.

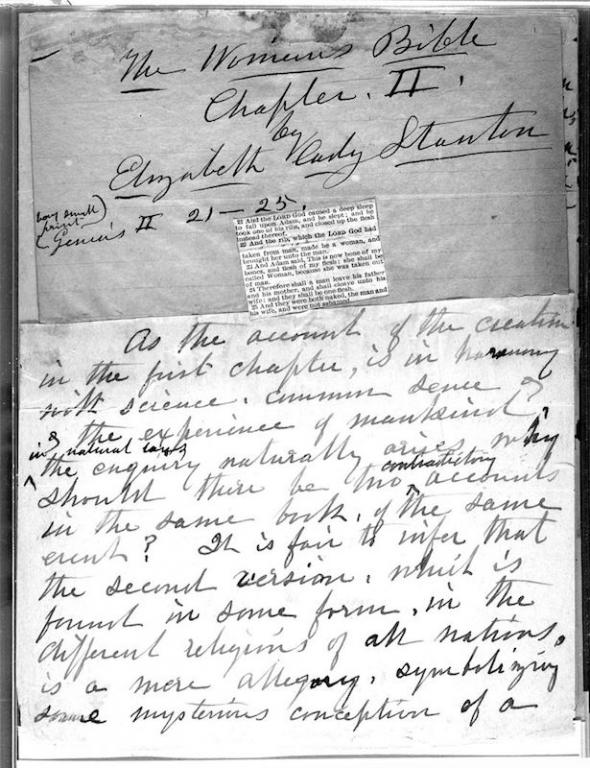

In this climate of hostility against women’s suffrage and their right to join men as equals in society, Gage showed no signs of being intimidated. She expressed her thoughts unflinchingly, but did not attack Christianity or Christians in a personal way. She merely discussed this misogynistic form of Christianity as a sociopolitical phenomenon. Still, when the ranks of the National Woman Suffrage Association swelled with Christians who did not share Gage’s views regarding separation of church and state, her book was denounced by the association. Also denounced was Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s The Woman’s Bible, which taught that there had originally been a creation myth in Genesis that recognized a female aspect of divinity, that woman could be seen as co-creator of life, a partner to man rather than an inferior. Clearly, Gage and Stanton saw the power of myth in the shaping of thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors; they shared alternative perspectives in hopes of helping women and society to find a healthier way of life. These examples of their work were rejected as radical by later members of the National Woman Suffrage Association, but they are now recognized as important contributions.

Gage was one of many white suffragists who held a certain amount of class privilege, but who also was denied rights and opportunities that Native American women possessed. There were suffragists who saw how things could be different in European-American society if women were not culturally invisible but respected, as they were in the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) culture. They looked to this culture as an example of an inclusive society where community and teamwork thrived, and each individual was considered a valued member with an important voice; women were respected as contributors and decision-makers. Their rights to their children and property were respected in the tribe (which was matrilineal), and violence against women was not part of their culture.

Gage was contemporary with Native Americans who honored woman as an earthly expression of divine life-giving sustenance. Long before the colonization of Europeans, they had banded together as a unification of tribes that stood strong in peace for hundreds of years- the Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, Seneca, and later, the Tuscaroras. Well known as the Iroquois Confederacy, they called themselves the Haudenosaunee, meaning “people of the longhouse.” Initiated into the Wolf clan of the Mohawk tribe, Gage had a meaningful connection with their community, and devoted a great deal of time and energy to learning about their culture, which influenced the women’s rights movement, American ideals of equality and community, and the Constitution of the United States of America. Women of the suffragist movement sought to emulate Haudenosaunee women, even in their style of clothing.

Though Matilda Joslyn Gage fought hard for woman’s suffrage and equal rights, she would never know the freedom of being able to vote legally. Towards the end of her life, in 1893 she was arrested for voting in a public school board election in her hometown of Fayetteville, NY. The 19th Amendment, which prohibited gender from limiting an American citizen’s right to vote, was passed August 18, 1920, twenty-two years after her death. It took seventy-two years for American women to get the vote. Her name may not be as well known as those of her contemporaries, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, but Gage and her message are now being rediscovered. Perhaps America is now ready to fully appreciate this courageous leader who was ahead of her time in so many ways, sharing an alternate perspective on religion, promoting the value of tribal inclusion and equality, teaching self-love, and the sacredness of woman. Her ideas about government and social issues are thought-provoking, many of them still relevant in current times – especially as separation of church and state continues to be a point of contention in American society.

There are many examples of lasting effects of Gage’s work and insights. Her ideas about gender equality and female leadership influenced her son-in-law, L. Frank Baum, author of the original Wizard of Oz series. His work featured some of the world’s most famous female characters, some of whom were witches. Glinda the Good Witch is an example of a witch who is not depicted as ugly and evil, but beautiful and kind. Certainly the Oz books helped to shape pop culture ideas about witches, and now they are not seen exclusively as evil women who should be thrown away, but powerful people with wills of their own. Additionally, Gage’s influence is evident in modern neo-Pagan culture where we continue to discuss the witch trials as an example of social injustice that made a tragic imprint on history, and set a precedent for misunderstandings and problems still lingering currently. Also in Pagan culture, we see the divine feminine celebrated by so many, and empowerment found by many women through roles such as witch and priestess.

Even today, it is easier for people to join movements once it has become fashionable to do so, after others have taken risks too daunting for most. Matilda Joslyn Gage was among those who paved the way in pursuit of women’s liberation, later to be joined by people who did not appreciate her work. Still she persevered, not allowing this to interfere with her will to speak, to write, to open the eyes of people who might benefit. Refusing to silently comply with the injustice of her society, she insisted on sharing her views no matter how radical they were considered. Her life tells a story of unwavering courage, a willingness to risk security, comfort, and social acceptance in order to live by what is right rather than what is popular. Though she died before the twentieth century, her memory lives on as a powerful example of someone who did not allow the restrictive ways of her times to define who she was, how she lived her life, and what she accomplished. The idea of a woman speaking and leading should not be radical but, still, to this day many women face challenges while trying to do so. In the eyes of many, it is still seen as a threat to convention, something a witch would do.

Gage, Matilda Joslyn. (1893) Woman, Church and State. Chicago, C. H. Kerr.

Kramer, Heinrich & Sprenger, James. (1487) Malleus Malificarum. Speyer, Germany

Wagner, Sally Roesch. (2001) Sisters in Sprit. Book Publishing Company

Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation (2018): www.matildajoslyngage.org

All photos by the author unless otherwise indicated.