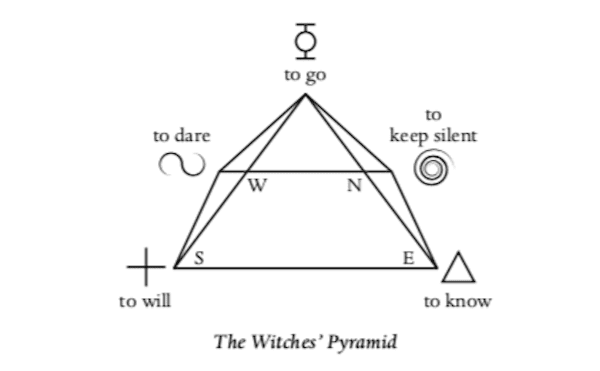

The Witches’ Pyramid is a magickal philosophy that predates Modern Witchcraft and was first articulated by the French occultist and magician Eliphas Levi (1810–1875) in his two-volume Transcendental Magic: Its Doctrine and Ritual, released in 1854 and 1856. In Transcendental Magic Levi writes:

“To attain the SANCTUM REGNUM, in other words, the knowledge and power of the Magi, there are four indispensable conditions an intelligence illuminated by study, an intrepidity which nothing can check, a will which cannot be broken, and a prudence which nothing can corrupt and nothing intoxicate. TO KNOW, TO DARE, TO WILL, TO KEEP SILENCE such are the four words of the Magus, inscribed upon the four symbolical forms of the sphinx.” (1)

For Levi, the magi were the carriers of magickal tradition. Just before introducing his readers to what would become the Witches’ Pyramid, he writes that “magic is the traditional science of the secrets of nature which has been transmitted to us from the magi.” (2) In Levi’s world, in order to become a successful magician one must be like the magi, and to be like the magi one must adhere to the four principles of “to know, to dare, to will, to keep silence.”

Levi is quite explicit in what these four principles mean. To be a magician, one must know one’s craft and study, and be fearless in that study, afraid of nothing that it might reveal. This requires an iron constitution and a deep inner strength, along with a sense of judgment unhindered by outside forces. Because Levi equates his four words of the magus with the legendary sphinx, his indispensable conditions are sometimes referred to as the Four Powers of the Sphinx. In ceremonial magick circles they are often called the Four Powers of the Magus (or Magician). The term Witches’ Pyramid is used exclusively in Witchcraft and was most likely first used in the 1950s, seventy-five years after Levi’s death.

Levi was a tremendously influential magician and thinker, and his four powers were picked up by the Golden Dawn as well as Aleister Crowley (an initiate of the Golden Dawn), who incorporated them into his practice of Thelema. Crowley introduced a fifth idea into Levi’s powers, the power “to go.” Crowley’s addition would eventually make it into some Witchcraft traditions where “to go” is equated with the element (or power) of spirit.

Modern Witchcraft has a long history of being influenced by ceremonial magick, so it’s not surprising that many Witches picked up on the ideas of Levi. The first book containing Modern Witch rituals, Paul Huson’s Mastering Witchcraft (1970), mentions the Witches’ Pyramid as an essential magickal first step. Instead of using the familiar “to know, to will, etc.,” Huson writes about the four powers as “a virulent imagination, a will of fire, rock-hard faith and a flair for secrecy.” (3) These ideas sync up nicely with Levi’s original vision and remove any ambiguity in the meaning of the Four Powers.

The first book to feature complete Witch rituals published by a major press was Lady Sheba’s Book of Shadows, published in 1971. In that work Sheba begins with the Witches’ Pyramid, which she calls the “foundation” of Witch power. Like Huson, she doesn’t use Levi’s short-and-sweet phrasing but instead describes the four sides of the pyramid like this:

“The first side of the four so-called sides of the pyramid is your dynamic, controlled will; the second, your imagination or the ability to see your desire accomplished; third, unshakable and absolute faith in your ability to accomplish anything you desire; and fourth, secrecy—“power shared is power lost.” …

“These four things, will power, imagination, faith, and secrecy are the basic rules and the absolute basic requirements for the working of Witchcraft.” (4)

Huson’s and Sheba’s books have been wildly influential over the last forty-plus years and are worth mentioning here because they are the foundation of “do-it-yourself” Wicca outside of an established tradition. By writing about the Witches’ Pyramid, they guaranteed that it would be a part of numerous Witch traditions and practices, and that its ideas would be shared, debated, practiced, and elaborated on long into the future.

As Witchcraft has grown over the last seventy years, the Witches’ Pyramid has grown alongside it, with each of its four tenets being given additional meaning. As with most things pertaining to the Craft, there are several different interpretations of the Witches’ Pyramid, and it’s possible that other authors and Witches will disagree with my understanding of them. Traditionally the four sides of the pyramid are thought to build upon one another, which means that without knowing, there can be no daring, etc. With that being said, here are my thoughts on each of the four sides of the pyramid.

To Know: There are many different types of knowing, which makes the first lesson of the pyramid open to several different interpretations. As Witches we should obviously possess a degree of book knowledge and an understanding of how our practices work, but “knowing” is a continual process. We don’t have all the answers once we are initiated or make our first contact with the Goddess. We must be dedicated to seeking wisdom and truth in our lives.

Knowing is also about what is inside of us. Answers exist both within ourselves and out in the greater world. A wise Witch knows not to give up on their dreams and desires. After all, it’s often our dreams and wishes that fuel our magick and give us hope when things look bleak. Creative visualization—the ability to see what we want in our mind’s eye—is one of magick’s foundations. “To know” is often associated with the element of air.

To Dare: Magick is often uncomfortable. We might create the cone of power to the point of exhaustion, and for many of us, simply finding Witchcraft required a gigantic leap of faith. Even though Witches in the West don’t face the level of discrimination they did just thirty years ago, this is still a path that sometimes comes with negative consequences. To be a Witch is to dare to be different, to live a life that’s different from one spent in the throngs of mundania.

Though standing in sacred space is not often equated with bravery, I believe that it’s a very brave act. To walk in the footsteps of goddesses and expose yourself to things greater than us humans takes courage, but Witches dare to do such things. As Witches we also explore the feelings and emotions that exist inside of us, and often these are things that we might find disturbing. But we do this as Witches because we want to explore our worlds both within and without.

The mantra “to dare” is often associated with the element of water, the element of death and initiation. Death and initiation are both journeys into the unknown, and such rites of passage require bravery and daring.

To Will: When I call upon my will during a magickal operation, I’m using all the collective energy and experience I have inside myself to create a new reality. Our will is what manifests change, and if we don’t utilize our will we won’t get the results we are looking for in our magickal work. Our will also applies to the tools we have at our disposal outside of ourselves; our will fuels the internal fire that gives us the desire to study and learn.

Our will is also about overcoming roadblocks and getting around obstacles and obstructions that stand in the way of our goals. In its purest form, the inner will is reflective of who we are as people, and most every Witch I’ve ever met is steadfast and determined. When circumstances are difficult, the Witch overcomes those challenges out of a sheer desire to succeed. “To will” doesn’t mean that we will always be able to solve every problem thrown at us, but it does mean that we are capable of getting past them. The will has always been associated with the element of fire, and that’s no different in the Witches’ Pyramid.

To Keep Silent: Levi originally called the last leg of the pyramid “To Keep Silence,” but most Witches today use the better-sounding “to keep silent.” Silence can refer to many things. It’s about the power of listening and saying nothing when the time calls for it. It’s about the still, small voice inside ourselves that often offers wisdom and guidance. Instead of offering excuses for our failures, it’s often better just to be quiet and accept the truth of our failings so we can learn from them.

Silence also extends to other Witches. A Witch should not “out” another Witch unless they have permission to do so. (It’s easy to understand why this was an extremely important principle fifty years ago.) There’s also power that comes with being silent about our magickal operations. If we broadcast what we are doing magickally, we risk the possibility that our magick might be countered or interfered with in some way. Most magickal operations are better off not being spoken about. “To keep silent” is often associated with the element of earth.

To Go: This is not traditionally a part of the Witches’ Pyramid, but some groups use it for a variety of purposes. “To go” can be seen as the end result of using the four sides of the Witches’ Pyramid, meaning once we figure out those pillars, we know how to go forward with our magick. Since “to go” is often associated with the element of spirit, the pyramid’s four columns are seen as supporting that power.

The Witches’ Pyramid is often pictured as a pentagram, with spirit as the top or defining power. (The right-side-up pentagram is often thought to represent the triumph of the spiritual over the material.)

I use the Witches’ Pyramid as one of the essential pieces of knowledge shared in the second-degree elevation rite later in this book, though there are other uses for it when designing your own rituals. It can be used as a password, with every Witch being asked to go through the pyramid upon entering ritual space. It can also be used as a challenge during such rites, with prospective initiates asked to recite the Witches’ Pyramid or explain its meaning.

Adapted from the book Transformative Witchcraft: The Greater Mysteries, Llewellyn Publications, 2019. You can purchase Transformative Witchcraft at most major booksellers and your local Witch-shop. The link above will take you to Llewellyn’s site. If you must buy it on Amazon, that link is here.

I’m really proud of this book, and hope you might consider picking it up. I share more of the book in this article on Initiation in the Ancient World: Eleusis.

NOTES

1. Levi, Transcendental Magic, 30

2. Levi, Transcendental Magic, 29.

3. 137. Huson, Mastering Witchcraft, 22. Originally published in 1970. My copy is the 1980 Perigree edition. Huson’s book is the first to contain Witch ritual that resembles Modern Witch rituals.

4. Jessie Wicker Bell (Lady Sheba), The Grimoire of Lady Sheba. I’m quoting from the Centennial Edition published on Llewellyn’s 100th birthday.