(Adapted and excerpted from The Book of Cernunnos, edited by John Beckett & Jason Mankey. Not surprisingly this was written by Jason Mankey since it’s his blog.).

Within much of Modern Paganism the most common male deity is known as “The Horned God.” Often thought of as ancient being, today’s Horned God is a modern construct, borrowing from literary and historical sources. Most certainly there were horned and antlered deities in the Ancient World, but the differences among those beings were vast. They were also generally unrelated. The Greek god Pan for instance shares absolutely no similarities with Cernunnos (antlers are not horns, and Cernunnos was never depicted with an erect phallus) and yet both of them are thought of as “aspects” of the greater Horned God.

Much of the language used in Modern Paganism to describe the Horned God comes from 19th century depictions of Pan in poetry and prose. Their Pan is written about as “the god” of wild spaces, the eternal Lord of the endless and joyous Summer. This way of looking at Pan is not an accurate depiction of his role in Greek mythology. Instead it was a then-modern gloss on the god, and an attempt to use him as a conduit for connection with the natural world.

In addition to Pan as a benevolent earth deity, he was also depicted as a god of sexuality. Not only is Pan mostly attractive to onlookers in poems, he’s also often actively copulating with those around him, and often the author. This depiction of Pan is far more accurate than the earlier one, though Pan was rarely thought of as attractive in the Ancient World. Today the modern Horned God construct retains the characteristics once used to describe Pan, but he generally doesn’t look like Pan. Instead, he most clearly resembles Cernunnos.

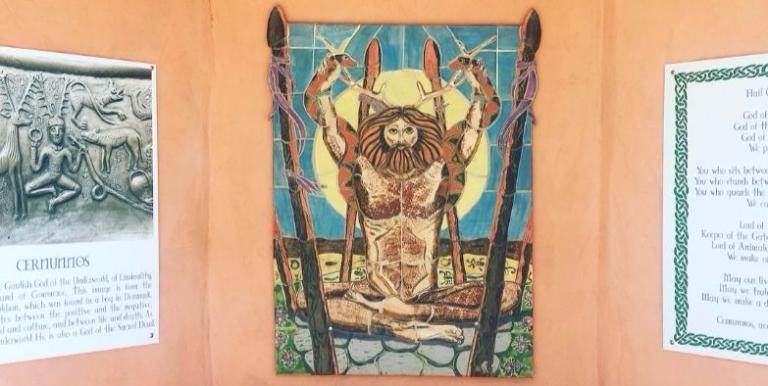

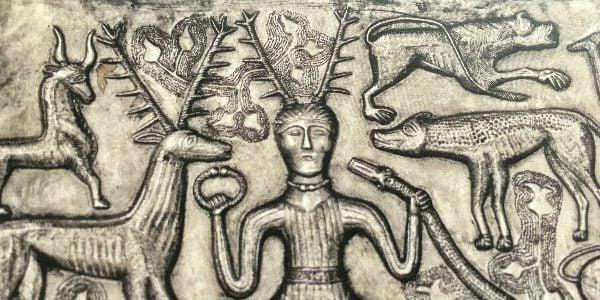

Do a Google Image Search of “Horned God” and you’ll end up seeing lots of figures that generally resemble Cernunnos. The horns atop this fig- ure’s head are usually not horns at all, but the antlers of a stag. He is often seen clutching a serpent or a torque, two objects traditionally associated with Cernunnos (and completely absent from any Pan myths). The god’s home is exclusively in the forest and he is often accompanied by a bow or sword and many wild animals (the latter drawing parallels to depictions of Cernunnos on the Gundestrup Cauldron). When shown with the legs of an animal, they are never those of a goat, but most often a stag’s, with many artists also using Cernunnos’s traditional sitting posture.

Like most people I did not grow up knowing anything about Cernunnos, and the deities I most dreamed about in my younger days were those of Greeks and the Norse. These were both pantheons with extensive mythologies, and have been a near constant presence in television, movies, comic-books, and “sophisticated” literature for my entire life. Cernunnos was completely unknown to me until I picked up my first book depicting Wiccan-Witchcraft in 1994.[1] Cernunnos’s placement in Conway’s book was not an outlier in the early 1990’s, instead it was representative of the steady progress Cernunnos had made into becoming the most recognized “horned god” in Modern Paganism. His rise to prominence can be traced through both purported academic works, and more popular books written especially for the modern Pagan and Witch communities. (I’m not suggesting that Cernunnos’s modern popularity is dependent solely upon written texts, as a devotee of the god, I like to think that He played a role in this as well.)

If I were asked to name the one individual most responsible for Cernunnos’s place in Modern Paganism I’d reply with Dr. Margaret Alice Murray (1863-1963). Murray was an Egyptologist by trade but became interested in the Witchcraft trials of the early modern period (1500- 1800) during World War One while unable to travel outside of her native England. Her research during the war led her to write The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921) published by Oxford Press.

Murray’s contention that Witchcraft was an organized religion in opposition to Christianity featuring a corrupted pagan deity transformed into the Devil, was never taken seriously by a majority of scholars, but Murray’s work found a sympathetic ear in the general populace. By the 1960’s her interpretation of the Witch trials had come to be considered “gospel” by many folks, a trend that continues into today. Murray’s follow-up book in 1931, The God of the Witches (published by Faber and Faber, a popular press instead of an academic publisher) focused exclusively on her corrupted pagan deity and would mark the arrival of both Cernunnos and the “Horned God” as major figures in the soon to commence Pagan revival.

What makes The God of the Witches so profound is how powerfully Murray makes her case. No longer appearing as he did in The Witch-Cult, as the Devil dressed as a “man in black,” Murray’s deity was now the Horned God (complete with the capital letters), and with a long and glorious history. Her Horned God was the most ancient of deities, stretching back to the 13,000-year-old figure known as “The Sorcerer” from Cave of the Trois-Frères in Southern France. From his cave origins, the Horned God then spreads throughout Europe, becoming known by a plethora of names including Pan, Herne, Robin Hood, and of course, Cernunnos.

Murray’s mention of Cernunnos was not casual either. In The God of the Witches she refers to him as:

“A few rock carvings in Scandinavia show that the horned god was known there also in the Bronze age. It was only when Rome started on her career of conquest that any written record was made of the gods of western Europe, and those records prove that a horned deity, whom the Romans called Cernunnos, was one of the greatest gods, perhaps even the supreme deity, of Gaul.”[2]

I find it unlikely that Cernunnos was the “supreme deity” in all of Gaul, but it’s impossible not to get caught up in Murray’s vision while reading this part of her book. Her Horned God was nature incarnate, and he came complete with rituals celebrating, life, death, and sex. When one finishes reading about Murray’s Horned God it’s something you find yourself wanting to go out and worship. (Never mind that Murray’s Horned God is completely illogical, full of huge gaps in time, and compromising several uncomplimentary deities.)

Twenty years later the “horned god” would reappear in Gerald Gardner’s (1884-1964) Witchcraft Today [3], as the god of a new and religious Witchcraft. But Gardner’s mention of a horned god would not be Murray’s only contribution to his text, she wrote the introduction to his book, sort of indirectly blessing the modern Witchcraft revival. Gardner, the English-speaking world’s first public, self-identifying Witch, is one of the seminal architects of the Pagan Revival, and he was most likely influenced both directly and indirectly by Margaret Murray.

Gardner’s 1959 follow-up book, The Meaning of Witchcraft, does not mention Cernunnos directly, but does include several mentions of the Horned God (now capitalized). One of those a description of the Horned One bears similarities to Cernunnos:

“Witches are constantly being accused of ‘worshipping the Devil’. Now, when we use that word ‘Devil’, what picture automatically forms itself in most people’s minds? Is it not that of a strange-looking being who seems to be partly human and partly animal, having great horns on his head, and a body covered with hair, although his face is human? Have you ever stopped to wonder why this picture should automatically come into your mind in this way? There is not one single text in the Bible which describes ‘the Devil’ or ‘Satan’ in this manner.”[4]

Gardner follows this description by linking his Horned God to Trois Freres and the Sorcerer in France, basically following the guidebook given by Murray.

Gardner’s Horned God is linked to modern ideas about Cernunnos in other ways. He writes of the Horned God as “the Lord of the Gates of Death” and “the dealer of death.”[5] But death would was not the only function of the god; to Gardner he was also the “provider of food” and when in a more poetic frame of mind Gardner writes that the Goddess and Horned God of Witchcraft:

“. . . . came because man wanted magical rites for hunting; the prop- er rites to procure increase in flocks and herds, to assure good fishing, and to make women fruitful; then, later, rites for good farming, etc., and whatever the clan needed, including help in time of war, to cure the sick, and to hold and regulate the greater and lesser festivals, to conduct the worship of the Goddess and the Horned God. They considered it good that men should dance and be happy, and that this worship and initiation was necessary for obtaining a favourable (sic) place in the After- World, and a reincarnation into your own tribe again, among those whom you loved and who loved you, and that you would remember, know, and love them again.”[6]

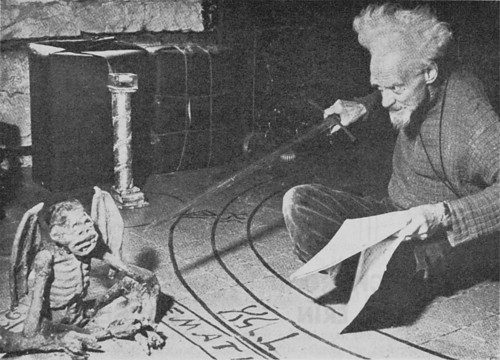

A little over ten years after The Meaning of Witchcraft, the first “how to” book on Modern Pagan Witchcraft was released by a major publisher. Until the publication of Mastering Witchcraft: A Practical Guide for Witches, Warlocks, and Covens by Paul Huson in 1970 (GP Putnam & Sons) the only way to obtain Witchcraft rituals was to either make them up yourself or become an initiate in an established coven. Huson’s work made it easy to establish one’s own personal Witchcraft practice, and not surprisingly, Cernunnos featured prominently.

Early in the text Huson calls Cernunnos one of the “so-called Witch deities” [7] he then later links Cernunnos to the imagery of Pan as part of a greater Horned One:

“The goat is the age-old representation of lust and debauchery, and Cernunnos himself, for such is his witch name, is frequently represented as possessing the cloven hooves, horns, and erect phallus of his attribute. His symbolism has much in common with that of the Greek god Pan . . . . . . . . Whenever you wish to perform a spell whose object is to boggle someone’s mind with lust, you should invoke holy Cernunnos . . .” [8]

At this point, at least in Witch literature, Pan and Cernunnos have for all intents and purposes become parts of the greater Horned One, with Cernunnos reigning as the “witch god.”

Cernunnos would also feature in Huson’s work as a god of vengeance. The god figures prominently in a work on poppet magick, which utilizes the power of Cernunnos to “vengefully stab the Dagyde (exorcised “nee- dles of the art”) into the part of the puppet designated for torment with the words ‘so mote it be!’”[9] Later in the same chapter on “Vengeance and Attack” the power of Cernunnos is used to call up an electrical storm (but only on Tuesdays).[10]

Huson’s work has been wildly influential over the last 50 years, and as the first “how to” book on Witchcraft ever published, his vision of Cernunnos has likely influenced thousands of people. Even today, it remains a best-seller on Witchcraft lists, and has found a second life as a guidebook for the emerging practice of “Traditional Witchcraft.”

Huson’s work is full of information, spells, and magickal formulas, but it’s light on Witch ritual. In 1971 the first mostly complete book of Witch ritual was published by Llewellyn Publications. Lady Sheba’s Book of Shadows (birth name Jessie Wicker Bell, 1920-2002) didn’t belong to Lady Sheba at all, but was originally an oathbound Book of Shadows belonging to a Witch coven in England. Sheba’s book is short on information but does contain eight sabbat rituals and the opening and closing frames of Wiccan-Witchcraft.

There Sheba lists the god and goddess of the Witches as “Arida and Kernunnos”[11] and repeats those names several times throughout her text. At the Spring Equinox Sheba’s work calls Cernunnos the “Merciful Son of Cerridwen” and states that his “name is Highest of all.”[12] The most common chant in the book features the lines “EKO EKO ARIDA, EKO EKO KERNUNNOS”[13] reinforcing the link between what I suppose is meant to be “Aradia” and Cernunnos.

Sheba’s work removes Cernunnos from his place as the god of vengeance (as seen in Huson) and returns him firmly to the realm of death. Her “Hallowmass Sabbat” (Samhain is linked to the Autumn Equinox in the work) features the Horned God Cernunnos (or Kernunnos) as “Dread Lord of Shadows, God of Life and Bringer of Death.”[14] This attribute first hinted at by Gardner, would become a familiar one amongst followers of the god.

Why Sheba uses the “K” spelling of Cernunnos is worth speculating on. It’s possible that the god’s name was spelled this way in the original Book of Shadows she received. Or perhaps she was attempting to recreate a name she had simply heard previously and had not seen written down. Sheba’s curious spelling would not become all that common, but it does show up from time to time in Witch books written in the 1970’s.

Links to Cernunnos and Pan would continue during the 1970’s, with Doreen Valiente (1922-1999) calling him “the Celtic horned god, similar to Pan” in 1978’s Witchcraft for Tomorrow.[15] In that same work she used a corrupted version of his name in her “Word of Power” again in combination with Aradia. “IA IA ARADIA! IO EVOHE KERNUNNO!”[16]

The most important Witch works of the 1980’s to feature Cernunnos were Eight Sabbats for Witches (1981) and The Witches’ Way (originally published by Robert Hale in England, and Phoenix Publishing in the United States, both books feature in the combined A Witches’ Bible in 1996) by Janet and Stewart Farrar. There not only is Cernunnos spelled properly, but he is again used as the principal male Witch deity, though not surprisingly he is again linked to Pan. (Written along with Doreen Valiente, Eight Sabbats for Witches is a previously unpublished Book of Shadows, allegedly influenced by Gardner’s covens.)

At the end of an invocation to Cernunnos the Farrars call Cernunnos the “Shepherd of Goats.”[17] Other than this aside, Cernunnos generally fills the roles first spelled out by Murray and Gardner: that of a deity of both life and death. In the work of the Farrars he also shows up again in the “Eko Eko” chants first published by Sheba, and his name is invoked at the start of every ritual. (The Farrars use him in their “opening frame” which is designed to begin every sabbat rite.)

Due to his appearances in books by the Farrars, Sheba, Huson, and others, by the 1990’s the image of Cernunnos had become the default “Horned God.” Cernunnos’s identification as “Celtic” (and not limited to his native Gaul) most likely also helped with the popularity of his image. In 1993’s To Ride a Silver Broomstick (Llewellyn Publications) Silver Ravenwolf calls Cernunnos “Celtic; Horned God and consort of the Lady. Also Kernunnos.”[18] Due to the prominence of Wiccan-Witchcraft in the 1990s and the rise of interest in “Celtic” music and mythology images and veneration of Cernunnos spread from Witch culture into the greater Pagan world, and have generally stayed there.

Today it’s impossible to visit a metaphysical store without seeing a modern interpretation of Cernunnos on a resin statue or plaque. Images inspired by him adorn necklaces and t-shirts from both independent Pagan artisans and mass marketers of consumer goods. Due to the god’s popularity in the greater Pagan world, it’s likely that his reach and power extend much further now than they ever did during his original heyday in ancient Gaul.

Hail Cernunnos.

Love Cernunnos? Pick up The Book of Cernunnos at the link!

NOTES

[1] That book was Celtic Magic by DJ Conway, first published by Llewellyn in 1990. Cernunnos is listed as “The Horned God” on page 106.

[2] My edition of God of the Witches was published in 2005 by NuVision Publications. This quote appears there on page 21. The edition I have is identical to Murray’s 1931 edition.

[3] Gardner’s book has a few things in it we would identify today with Wiccan-Witchcraft, and a lot of other stuff that doesn’t really resonate. In the book he makes only one reference to a horned god of Witches, and doesn’t capitalize it.

[4] Gerald Gardner writing in The Meaning of Witchcraft, first published in 1959 by Rider & Co. I’m using the Magickal Childe edition from 1991. This quote appears on page 20 of that edition

[5] Ibid, page 45.

[6] Ibid, page 25.

[7] Huson, Paul, Mastering Witchcraft, Perigree/Berkely books, 1970, page 32. I’m quoting from the Perigree Books edition from 1980.

[8] Ibid, pages 120-121

[9] Ibid page 196,

[10] Ibid page 201

[11] Bell, Jessie Wicker, The Grimoire of Lady Sheba, Llewellyn Publications, originally published in 1972, I’m using the 2001 hardback edition, page 119. The Grimoire was released a year after Lady Sheba’s Book of Shadows, and includes the original Book of Shadows and additional material.

[12] Ibid, page 205.

[13] Ibid, page 227, and other places.

[14] Ibid, page 237

[15] Valiente, Doreen, Witchcraft for Tomorrow, Robert Hale Ltd., 1978.

[16] Ibid, page 163. Here she also includes the names Diana and Pan.

[17] Farrar, Janet & Stewart, The Witches’ Bible, Phoenix Publishing, 1996, originally from Eight Sabbats for Witches.

[18] Ravenwolf, Silver, To Ride a Silver Broomstick, Llewellyn Publications, 1993, page 53.