If there was once a Hyperborean culture in the North with a shamanic ethos, then it is likely to have included the common shamanic practice of using psychedelic drugs to induce altered states of consciousness. And indeed, we find that most, if not all, of the circumpolar shamanic traditions involve the use of narcotic plants such as fly agaric or Amanita muscaria, the mushroom with the distinctive red cap and white spots.

Long ago human beings discovered that one way to imbibe the psychoactive component of the amanita was to drink the urine of a person or animal that had eaten the mushroom. This used to be a common practice among the Inuit (1) and apparently still is among the Sami of northern Europe, who feed the mushroom to reindeer then collect and drink their urine.(2) Today the favored scientific term for such psychoactive substances, when used for spiritual purposes, is entheogens (from the Greek, meaning “generating the divine within”).

As the Nordic peoples also had a shamanic tradition, as we have seen, it is not surprising that we find disguised references to entheogens in the Nordic literature and mythology, as has been pointed out by the American scholar of religion Scott Olsen, who writes:

Odin drinks from the well of Mimir, the Well of Memory,

consumes the sacred mead (esoterically the psychotropic

Amanita Muscaria mushroom), and hangs inverted for

nine days on the Yggdrasil tree entering into non-ordinary

states of consciousness. Enduring this intense ordeal in an

expanded and timeless (nonlocal) state of consciousness, he

discovers the secret of the runes, the mathematical patterns

of Nature. While riding on the magical eight-legged Sleipnir

he descends on the winter solstice to seed the Amanita

Muscaria. This same plant is none other than the Hindu

Soma that transports the sage across the final divide. Its

description in the Rig Veda leaves no doubt that the Soma is

Amanita Muscaria. (3)

There are further details that confirm Odin’s character as a shaman. In order to obtain second sight, he sacrificed an eye by throwing it into the well or fountain of Mímir, one of the three fountains at the foot of Yggdrasil. He is accompanied by two wolves and two ravens, typical of the animals that function as shamanic totems or accompany shamans on their trance journeys, and he rides a horse called Sleipnir which has eight legs, another shamanic motif. Furthermore he could change his shape and perform weather magic, as the Ynglinga Saga tells us: “Odin could transform his shape: his body would lie as if dead, or asleep; but then he would be in the shape of a fish, or worm, or bird, or beast, and be off in a twinkling to distant lands upon his own or other people’s business. With words alone he could quench fire, still the ocean in tempest, and turn the wind to any quarter he pleased.” (4)

Olsen takes the Nordic connection with shamanism further and sees the symbol of the hammer of Thor as a representation of an amanita mushroom. Often the hammer is shown with a series of small dots, which he believes represent the white dots on the mushroom. (5)

As Olsen points out, the shaman’s trance can be a way of accessing higher knowledge and obtaining profound philosophical or scientific insights. He compares shamanism with the system of higher magic in the ancient world known as theurgy. According to one of its practitioners, Iamblichus (c. 245–325 CE), “the objective of the theurgist was to use ritual actions to resonantly identify with aspects of the Divine Source which was accomplished through recognition of the numinous cues, tokens or ‘signatures’ of the Divine present in our world, progressively ascending to the non-material ‘ratios and proportions’ that ultimately lead the soul back to the Divine Source.” (6)

As a more modern example, Olsen mentions the Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887–1920), who “confounded his colleagues by producing amazing continued fractions” through connecting with his family goddess Namagiri. “When the resonant connection was successful, he had visionary dreams of drops of blood that symbolized her male consort, the Lion-Man Narashima. Visions of scrolls then appeared with complex mathematical equations unfolding before him.” (7)

Such visionary flights of illumination among the northern shamans could account for the appearance of Platonic solids in Neolithic Scotland, as mentioned in the previous chapter, and the complex mathematics of the megalithic sites, including the frequent use of the golden section. This kind of illumination might also be what Odin achieved through his ordeal on Yggdrasil when he discovere the secret of the runes, which, as we shall see in next chapter, have profoundly subtle mathematical dimensions.

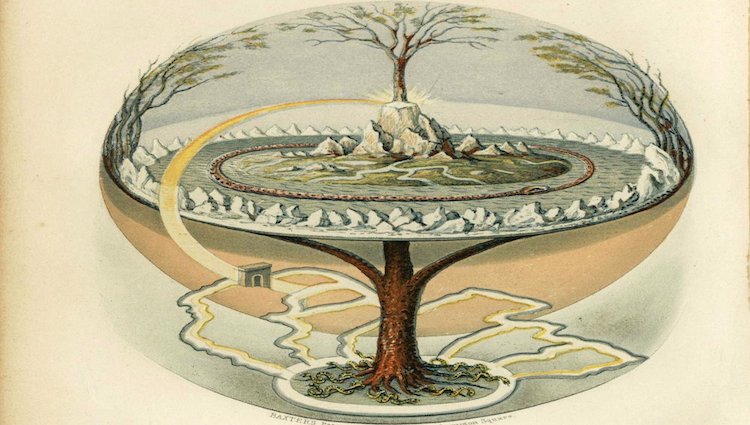

Yggdrasil itself is also a shamanic symbol. It is so named because Yggr is one of Odin’s names, and drasill means “steed” or “gallows.” Yggdrasil encompasses nine worlds: the world of human beings, the world of the gods and goddesses, the world of the giants, the worlds of the light elves and the dark elves, the worlds of fire and water, the world of the dead, and the nether world of darkness and fog. The motif of the tree plays a role in many mythologies, often symbolizing the central axis of the world, the axis mundi, which connects different levels or realms. While in Yggdrasil there are nine worlds, more often in shamanic tradition there are basically three: the world of the gods, the everyday world we live in, and the underworld of the dead. Sometimes the tree is purely a symbol; sometimes it’s an actual tree.

We find counterparts of Yggdrasil in many cultures. Sometimes it is symbolized by a tent pole, as with the Siberian shaman and the Native American medicine man. We find it also as the bodhi tree under which the Buddha obtained enlightenment. We find something similar in the Jewish Kabbalistic Tree of Life, and there is the interesting example in Chinese mythology of the Kien Mu tree, which grows at the center of the world and has nine branches reaching out to nine heavens and nine roots reaching out to nine springs where the dead have their abode. So it is very similar to Yggdrasil and possibly an example of the transmission of the northern tradition far beyond its original home.

There are various beings that dwell in Yggdrasil. There is a squirrel, Ratatosk, who carries messages up and down the tree. There is a cock, symbol of watchfulness and protection, who is perched at the top of the tree to keep a lookout for danger, the so-called Cock of the North (Fig. 8). This may possibly be the origin of the custom of putting a weather vane in the form of a cock on top of a church steeple. Then at the base of the tree are three fountains or springs. One is the already mentioned fountain of Mímir, the god of wisdom. Then there is Hvergelmir, a swirling, bubbling spring which is the source of all the rivers of the world. And there is the fountain of Urd, which is associated with the three Norns or goddesses of fate: Urd, Verdandi, and Skuld, who correspond to past, present, and future.

Adapted, and reprinted with permission from Weiser Books, an imprint of Red Wheel/Weiser, Beyond the North Wind by Christopher McIntosh is available wherever books and ebooks are sold or directly from the publisher at www.redwheelweiser.com or 800-423-7087.

NOTES

1. https://www.iamshaman.com/amanita/inuit.htm

2. http://andy-letcher.blogspot.com/2011/09/taking-piss-reindeers-and-fly-agaric.

html

3. Olsen (2017), 16.

4. Ynglinga Saga, 7. http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/heim/02ynglga.htm.

5. Lecture delivered at the New York Open Center conference “An Esoteric Quest

for the Mysteries of the North,” Iceland, August 2016.

6. Olsen (2017), 14.

7. Olsen (2017), 15.