I’m glad Birdman won best picture last night. It’s a strange film, to be sure. Unsettling, too.

By now most people reading this know the basic premise of the film: A former Hollywood mega-actor who played a superhero in the heyday of one rendition of that superhero franchise (during the 1990s) finds himself struggling to discover a sense of significance in his waning years. The glory of the”Birdman” has faded. Now he wants to do something serious to prove himself as an actor and to regain some of that lost glory. So, naturally, he makes the move to the Broadway stage. Throughout the film, he interacts with his ex-wife, his daughter, his new girlfriend, and–most importantly–a version of his inner “self,” desperately trying to pull him back into the limelight that he “deserves.” We observe the destruction that has followed his career, as his failed marriage and his broken relationship with his daughter remain front and center as living monuments to his desperate attempts at significance. This comes to a point in his daughter’s brutal confrontation speech, along these lines: “None of this matters. We are not important! You are not important!”

A Facebook friend commented recently that he was disappointed that Birdman won the Oscar, because he doesn’t see it as nearly as relevant as the other candidates. I suspect what’s behind the comment is that, at one level, it could be read as a “movie about  movies,” a “meta” film–actors and directors putting on a narcissistic and nihilist self-reflection; a dark comedy about their own craft. But I think there’s more to it than that. I think, in a sense, it’s a movie about a lot of us human beings in the (late) or (post)modern world. It’s a story about the quest for significance, the attempt to latch on to some sense of immortality through legacy, a last-gasp at meaning-making in a crazy, often-random-as-hell world. We all want to know that we matter, somehow, and we often do everything we can (everything but those simple, mundane things that actually matter) to feel that we do.

movies,” a “meta” film–actors and directors putting on a narcissistic and nihilist self-reflection; a dark comedy about their own craft. But I think there’s more to it than that. I think, in a sense, it’s a movie about a lot of us human beings in the (late) or (post)modern world. It’s a story about the quest for significance, the attempt to latch on to some sense of immortality through legacy, a last-gasp at meaning-making in a crazy, often-random-as-hell world. We all want to know that we matter, somehow, and we often do everything we can (everything but those simple, mundane things that actually matter) to feel that we do.

The movie begins memorably: “Birdman” Riggan Thompson is meditating, and levitating, in his underwear. We see a man past his prime; this is no superhero. This is a body that smacks of pure normalcy: aging, dwindling, even asymmetrical. This is a man whose body has not kept up with his mind (or more particularly, his image of what his body means). This opening scene names the disconnect that is at the core of all human beings: we are finite flesh, but we have ethereal thoughts and we dream of immortality. We dream, symbolically, of “being something” and of mattering. But then we find ourselves running through Times Square in our gruesomely normal bodies, wearing nothing but whitey-tighties.

Ernest Becker, in The Denial of Death, argues that at the root of human beings is a “need for heroism.” We want to overcome our banality, or embodiment, our primitivity, by constructing a hero-self. As Kierkegaard also well knew, our fundamental source of internal conflict is the tension between our bodies and our spirits. We are animals, but animals on whom eternity has shone its light. Becker cites the psychologist Eric Fromm, who wondered,

…why most people did not become insane in the face of the existential contradiction between a symbolic self, that seems to give [humanity] infinite worth in a timeless scheme of things, and a body that is worth about 98 cents? How to reconcile the two?

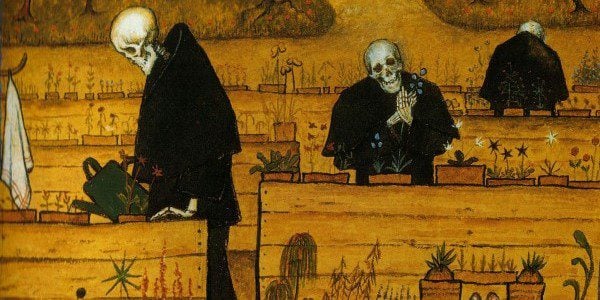

Culture frames up as a kind of collective human response to this question and if offers a seemingly infinite number of pathways to heroism. Culture not only accommodates the quest for heroism, it stimulates and encourages (and also perverts it). The superhero is, well, a super-hero. The notion of the super-hero as the ideal form of the very best self that we could ever imagine ourselves being, gets into us from a very young age. My 2 year-old son is fascinated with superheroes (the Batman in the picture is his). And by the way, I never said to him, “you should really like Superheroes, son.” The drive toward heroism is apparently in the air we breath and it is received intuitively, perhaps, as a way out of the human predicament caused by the class between body and mind, flesh and consciousness, and by the very instinctual desire for survival by rising above the perils of the earth. We want to become heroes because in so doing, we convince ourselves that we are immune to the frailties and vulnerabilities that otherwise besiege us at seemingly every turn.

So what then must we do? Becker suggests,

…to become conscious of what one is doing to earn his feeling of heroism is the main self-analytic problem of life. Everything painful and sobering in what pscyhoanalytic genius and religious genius have discovered about [human beings] revolves around the terror of admitting what one is doing to earn his self-esteem.

In other words, we ought not deny the condition that we find ourselves in. We dare not listen to the voice of the “Birdman” who tells us that we “deserve” to rise above all the other creatures of this earth and who tries to convince us that super-humanly, valiant hero efforts, no matter the cost to human relationships, is our best pathway through life. Such a path might lead, ironically, to our tragic end. Instead, let us recognize and embrace our frailty, and find significance in lasting and meaningful relationships. Let’s breath the air again and feel the ground under our feet. No need to fly.

The same reason I liked Birdman is also why I hated it: It reminded me of myself. Reaching for significance, clamoring for a sense that I matter–that what I do it important and lasting and recognized. But just when I think I might be gaining ground on this ongoing goal toward “heroism,” I find myself running around in my underwear. But if that’s the situation we all face, maybe it’s not so bad.