Martin Luther distinguished a theology of glory from a theology of the cross. A theology of glory looks to avoid suffering and sacrifice, and takes “victories,” accomplishments, and political or social stature to be signs of God’s favor. A theology of glory is comfortably nestled in Christendom, with all the comforts and pleasantries it provides. A theology of glory works well when things are going well. A theology of glory can be a marvelous way to assure the self-assured and to confirm a life of ease. It skips the

cross–and the deep, difficult, and mysterious questions raised by the cross–and goes right to the resurrection, assuming all is well. But a theology of glory can have a sordid side, too. It can motivate people to respond to evil in kind. It can lead to quick impulse responses; an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. Under the theology of glory, suffering (particularly, my suffering) seems out of place. Therefore, my suffering must be overcome at all costs. It is better that you, or they, suffer instead. The theology of glory stands behind the very theology of kingdom (read: Empire) that Jesus came to disrupt and transform.

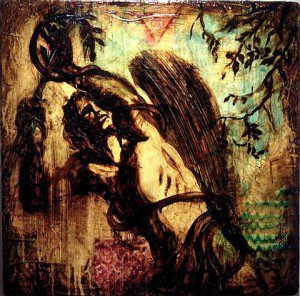

The theology of the cross understands that suffering is a part of life. It does not rush past the cross to get to the resurrection. Instead, it recognizes that before resurrection comes, we live in Holy Saturday; on this side of the resurrected body, the restored cosmos, and the eternal city. The theology of the cross does not take the absence of suffering as a sign of God’s favor. Instead, it wrestles with the profound unknowing that characterizes so much of this life. It struggles with the apparent absence of God (the hiddenness of God) even, some would add–though I cannot go that far–the death of God.

Today’s theology of the cross has little interest in the metaphysical features of the “onto” God of classical theism, with all the “omnis” (omniscience, omnipresence, omnipotence) and all the “ims” (immutable, impassible, etc.). The God of the theology of the cross is a God who enters fully into the suffering of the world, who is defined not so much by the “omnis” and “ims” as by the “ins” and the “withs.” That is, a God who with is through our pain, who suffers with us as on the cross and who is in our suffering and in the brokenness of the world, even now.

The theology of the cross is not given to countering might with mightier, or strength with stronger, or violence with more violence. The theology of the cross underlies a response of lament and brokenness, solidarity and patient struggle.

As we struggle to comprehend the atrocities done by ISIS, with their deeply misguided (yes, and evil, no doubt) apocalyptic and horrifically violent eschatology being played out in real time, as they attempt to usher in the end of the world and the establishment of their reign through the spilling of blood (a theology of glory, if ever there was one), perhaps Christians should deeply consider what insights the theology of the cross has for us today. This is not to say that the use of violence to counter or perhaps even eradicate ISIS will not be necessary to protect the lives of so many innocents and to end the terror. But the use of violence will not–it cannot–be driven by a theology of the cross. And as I hear some of the reactions on social media and elsewhere (and as I reflect on my own instinctual reactions), we would be wise to recall the witness of the theology of the cross. This may be the best way to not play into the hands of evil, who want–even who need–an adversary to continue to fuel their own endeavors of violence and to heighten their apocalyptic urgency. Can the church, by drawing on this deep well, offer up an alternative way of reacting to this horror? Might it, paradoxically enough, be a better way to undo its power (as incredible as it may seem)?

Because the temptation is to return to our usual responses to violence and terror (responding in kind), we need a theology of the cross now more than ever.