This is the second post of a series I will be writing over the next few months in which I reflect on my theological journey through Evangelicalism and “out the other side.”

When I first starting teaching theology, I discovered the significance of context. This might sound strange and indeed, it is strange that in eight or so years of theological education (seminary and doctoral studies) in Evangelical settings, context was so little discussed and so underestimated. Now, when you study Church History, of course context comes into play. When you do “biblical interpretation” and hermeneutics, you discuss context. But in many Evangelical settings (at least the ones I experienced), context is their context. You need to know their context so as to better understand them. Or you need to know the biblical context so you can rightly interpret the text rather than “eisegete” it.

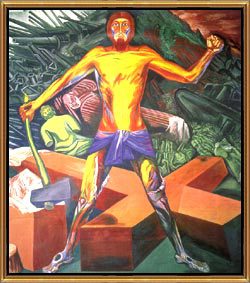

But as I dove into a whole new level of research to teach Systematic Theology, I was confronted with my context and with the fact that white, mostly male, American Evangelical theology is its own context and is fundamentally no different in that respect than all the contextual theologies which are so often marginalized in Evangelical theology. The mantra began to beat in my head like a drum: All theologies are contextual–even the ones that don’t claim to be. And interestingly, American Evangelical theology represents a pretty recent context in the long scope of history.

What did this all mean? It meant that I have presuppositions, thanks to my embedded (received) theology, and I have biases, blind-spots, and a very limited take on reality. My view of God, my God-images, are shaped by the particular experiences of my life and of my pretty narrow theological and church tradition not to mention my particular ethnic, gendered, and embodied experience.

And I’m supposed to have a definitive take on God from within these contextual limitations?

I’m supposed to have a definitive interpretation of the Bible from within these contextual limitations?

The anxiety about theological and epistemological certainty, which I discussed in my last post, had already faded from my expectations at this point. I had begun to replace “certainty” as a theological goal with “confidence,” or–if you want a stronger, more emotively religious variant–with “conviction.” All knowing is personal knowing (Polayni), truth is subjectivity (Kierkegaard), theology is contextual.

The realization of the shaping significance of context didn’t meant that all is lost, so I should throw up my hands in despair at not being able to ever know anything. It meant that I shifted from aiming for epistemological certainty about theological matters (e.g. the “nature of God,” the “right interpretation of this or that text”) to being content with a settled confidence about some core values and convictions I had–while sorting through (as best I could) the presuppositions and biases that I carry with me.

Certainty is an inevitable human emotion. As Robert Burton points out in On Being Certain: Believing You are Right Even When You’re Not, there’s a special location of the brain dedicated to giving us the feeling of certainty. But certainty isn’t often connected to conscious reflection and reasoning (even though we often imagine it to be). So I’m certainly not claiming to never feel certain about things–or that if we feel certain, we should feel guilty. But it’s healthy to examine whether we are assuming that our sense of certainty is tied to a faulty assumption that we possess objective, final truth about God and that our particular context has not shaped our theological convictions in more ways than we may want to admit.

American Evangelicalism represents a context (or a constellation of relatively similar “contexts,” at the very least). Too often, though, its theologians and pastors fail to recognize their own contextuality (it’s easier to see how context influence others!). This is one reason I have shifted away from Evangelicalism. The theological certainty, based in assumptions about what can be known with definitive precision, became for me a problem too pervasive to avoid. I see that certainty exemplified in a common understanding of Scripture (i.e. the doctrine of inerrancy), a particular (and narrow) definition of the gospel, assumptions about Hell and the “final judgment,” and an aversion to the deep mystery of God.

But more about these things as we move along.