This is the second post of a series I will be writing over the next few months in which I reflect on my theological journey through Evangelicalism and “out the other side.”

Is the Bible completely and utterly and absolutely true? Is it completely and utterly true about everything (or even everything about which it speaks)? Can we take the Bible’s words and lay them up against what we know about history, and biology, and cosmology, and sexuality, and the size of mustard seeds in ancient Palestine? Is the Bible completely and utterly true when it says that God created everything in six days (and if it’s a “day,” then it must mean a 24 hour period, right?). And, when “truth” and “truthfulness” is used in the Bible, did they mean the same thing as Evangelicals mean by it?

Did Elisha’s ax-head really float (2 Kings 6)

Was Jonah really swallowed by a big fish and spat out 3 days later?

Did God really (I mean, really ) command Moses to kill all the Midianite men and non-virgin women, but to keep the virgins alive for the soldiers (Num. 31)? In other words, did God command genocide, slavery, and sex trafficking?

What do we do with all the violence, slavery, rape, and sexism in the Bible (see, for example, Phyllis  Trible’s Texts of Terror)?

Trible’s Texts of Terror)?

Did all those miracles really happen the way the Bible says they did?

Jesus really rise from the dead?

The questions are piling up. So why not more?

What does “true” mean? Propositionally (or “informationally”) true? Symbolically true? Mythically true? Theologically true? Relationally or existentially true? Or is “truth” just not the best word to use in every case and place regarding the Bible’s content? Does truth in the Bible mean something more like “faithfulness” than factual precision? (probably so).

When I applied for my first tenure track job at an evangelical seminary, I was asked this question about my view of the Bible: Is there any qualitative difference between the significance of whether or not the ax-head floated or whether Jesus really rose from the dead? My interviewer was getting at the so-called problem of the “slippery slope.” That is, if you say that one episode or story in the Bible did not really happen precisely in the way that it happened, then you are left in an epistemological lurch, because you have no solid ground upon which to affirm that some things really happened and that other things did not. I think my interviewer wanted me to say that there is no qualitative difference in terms of the truth of the matter: because every word in the Bible is absolutely true.

I don’t think my answered please him (though it pleased enough others in the room that I got through). There’s a big difference. One is an ancient story, possibly miraculous or possibly mythical; either way, it has no direct bearing on our lives or our faith. The other is about the ground of our hope in the resurrection of the living Christ. That Christ lives and acts redemptively today through the power of the resurrection, and gives us hope that we too will live again, matters deeply, personally, spiritually, and existentially. The biblical testimonies to the resurrection are pointers to that reality. They are pointers to the living Christ, who is the theological and hermeneutical centerpiece of the Christian canon. Like John the Baptist, they point the finger to Jesus; so the Bible creates an occasion for us to narratively engage the story of Jesus–but it is the living Jesus that is the goal. And God is the real authority; the Bible is a derivative authority. (This latter point, by the way, I adopted from N.T. Wright).

The definition of inerrancy which I used for many years as an evangelical is one I learned from my doctoral adviser: The Bible is literally true in all that it literarily affirms. In other words, we can assume its truth, but this is far from yet saying what it is true about. To get there, you have to undertake a complicated theological, hermeneutical, and interdisciplinary process which attends to all kinds of ways of knowing and all sorts of inputs of information (including, in my view, contemporary understandings of biology, cosmology, sexuality, ethics, etc.). This “intentional view” of inerrancy–that the Bible’s truth is related to the communicative intentions of the author (and must incorporate the limitations of the authors’ culture) is hardly distinguishable from the concept of infallibility (the Bible doesn’t fail to do that which it intends to do). It is so indistinguishable, in my view, that it’s probably not worth keeping the term inerrancy. Let’s just give that to the literalists and the fundamentalists, and call it a day.

The definition of inerrancy which I used for many years as an evangelical is one I learned from my doctoral adviser: The Bible is literally true in all that it literarily affirms. In other words, we can assume its truth, but this is far from yet saying what it is true about. To get there, you have to undertake a complicated theological, hermeneutical, and interdisciplinary process which attends to all kinds of ways of knowing and all sorts of inputs of information (including, in my view, contemporary understandings of biology, cosmology, sexuality, ethics, etc.). This “intentional view” of inerrancy–that the Bible’s truth is related to the communicative intentions of the author (and must incorporate the limitations of the authors’ culture) is hardly distinguishable from the concept of infallibility (the Bible doesn’t fail to do that which it intends to do). It is so indistinguishable, in my view, that it’s probably not worth keeping the term inerrancy. Let’s just give that to the literalists and the fundamentalists, and call it a day.

Inerrancy is tied to the notion of “plenary verbal inspiration”: Every word in the Bible is “breathed-out” by God and is therefore guarded by the Holy Spirit from the possibility of error. Evangelicals acknowledge that readers will err when they interpret. But, when everything is finally known, we will all see that the Bible’s words are completely immune from human error and that any assumed errors were just misunderstandings on our part. There are errors in the copies of the manuscripts, however (and we don’t have the pristine originals). But we’ve mostly remedied those errors (presumably) through careful textual replication. By the way, the “original manuscripts” concession has been dubbed, by a well-known Evangelical professor no less, the “run-to-the-round-room-they-can’t-corner-us-there” tactic.

And now, let’s jump into the problems with inerrancy:

(1) there are so many definitions of inerrancy that is has become a mostly meaningless word (perhaps like “evangelicalism” itself. As I suggested above, the positive impulse behind the term is better served by words like: “true, trustworthy, effectual, powerful,” and–perhaps most importantly–inspired.

(2) It is mainly a political and “power” word, a shibboleth useful for maintaining boundaries and for gatekeeping who is in and who is out. We see this time and again. We see the power-play, shibboleth narrative played out time and again in Christian denominations, colleges, seminaries, churches, etc. Often the conflict is over interpretations of Scripture, but very often the issue is directed back to assumptions about “inerrancy”–and to the way that is defined by those in power).

(3) The more literalist and propositionalist definitions of inerrancy just don’t square with the diversity, humanity (culturally embedded), and limitations of the text. They also make strong assumptions that the Bible itself proclaims its own “inerrant” nature. Upon closer inspection, it simply does not. Even the most widely used texts, like 2 Timothy 3:16-17, simply do not prove the more propositionalist (literalist) versions of the Evangelical position.

(4) The doctrine of inerrancy too greatly neglects the role of tradition and the “church catholic” in the formation of the canon. This is another way of saying that inerrancy undermines the humanity of the Bible. The portrait which emerges from “plenary verbal inspiration” is too often that of an impeccable, immune from human (fallible) input, book that just sort of drops out of the sky–rather than a collection of books that came to be stamped as authoritative over time through a rather messy process. And I haven’t even broached the issue of the contested canon between Protestants and Catholics!

(5) The doctrine of inerrancy is simply too modernistic and “objectivist” in orientation. As Donald Bloesch puts it, “”I am not comfortable with the term inerrancy when applied to Scripture because it has been co-opted by a rationalistic, empiricistic mentality that reduces truth to facticity.” In other words, inerrancy is bound up with a particular kind of epistemology: one which cannot account for the richness of truth and ways of knowing. Perhaps we should be looking to the Bible to do things other than (or at the very least, much more than, give us propositional doctrines, “rules for living,” even “theologies” of God that preclude mystery and that are very often bogged down by the humanity reflected by the biblical authors (i.e. Patriarchy).

(6) The doctrine of inerrancy is based on an epistemologically certainty that is simply untenable. It assumes that in the divine revelation given in Scripture, we have a kind of immediate access to the pure truth of God, shining through. But this is to neglect, as Gabriel Fackre points out in The Doctrine of Revelation, the “already and not yet” tension that the Bible itself teaches: “To hold that the original writings of Scripture in all the parts and on all their subject matter are so superintended by the Holy Spirit as to constitute them with an unqualified inerrancy is to confuse the present Dawn with the final Day” (170). This is why many Evangelicals reject the use of many higher critical methodologies: they have confused the “Dawn” with the “Day,” and are therefore looking to the Bible to give the the “Day,” right now.

(7) The doctrine of inerrancy too often accepts the biblical texts as they are rather than seeking to discern what they might be pointing us toward. If we were to only read the Bible literally (via the literalist doctrine of inerrancy), might have a difficult time denouncing some abhorrent things that the Bible does not denounce. War, violence, slavery, violent patriarchy, etc.). We need to think with–to theologize with and alongside the text. But we must also be willing to go beyond the confines or limits of a literalist, wooden reading of the text, as the Spirit leads us. To say this another way: a preoccupation with inerrancy can get in the way of justice and abundant life. What would Jesus want?

On top of it all, or perhaps underneath it all, is the sticky problem that the Bible just does contain “errors,” of various sorts. Rather than ignore these historical, chronological, scientific, moral problems, let’s take them up into a larger vision of God’s revelation, God’s truth, God’s salvation in Christ and the Spirit.

The Christian canon is an irreplaceable document for Christians and for the church. And it is, in my view, the inspired Word of God that can leads us into the knowledge of God. But it facilitates that relational knowledge of God. And God is the authority–not the Bible. Kierkegaard suggested that perhaps there are errors in the Bible (errors of history or grammar, etc.) that were intentionally allowed by God to keep us from putting our faith in the Bible, and allow us to put our faith in God.

Now there’s an intriguing thought.

photo credit: <a href=”http://www.flickr.com/photos/71401718@N00/3281031630″>Antique Holy Bible, printed in 1885, with metal clasps, and leather binding, Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, Mexico</a> via <a href=”http://photopin.com”>photopin</a> <a href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/”>(license)</a>

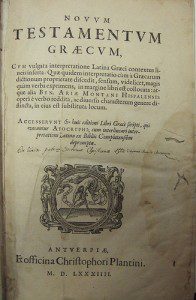

photo credit: <a href=”http://www.flickr.com/photos/66690468@N02/6672197399″>P16-512 titre 1</a> via <a href=”http://photopin.com”>photopin</a> <a href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/”>(license)</a>