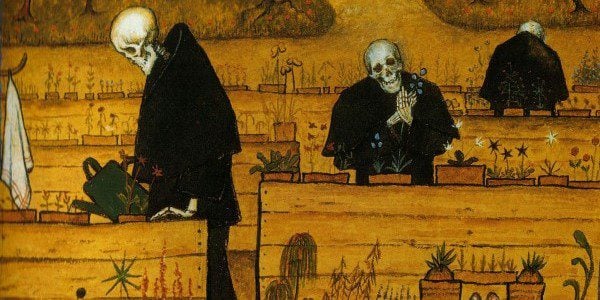

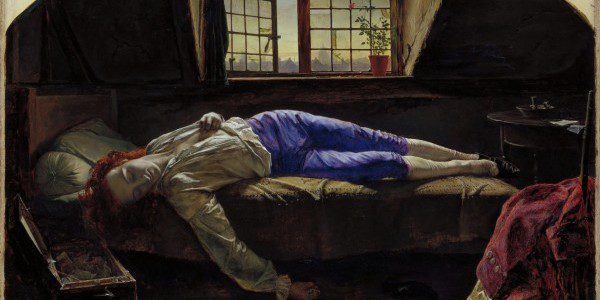

Tomorrow I begin teaching my fall course, Evil, Death, and Alienation (Don’t worry, students: I’ll throw in some cute kitten pictures here and there to lighten the mood). I’ve been looking forward to this course. Readers of this blog know of my ongoing interest in the work of Ernest Becker, in particular The Denial of Death.

So, as I wrap up final preparations for tomorrow’s class session, in which I’ll be showing a few fantastic clips of

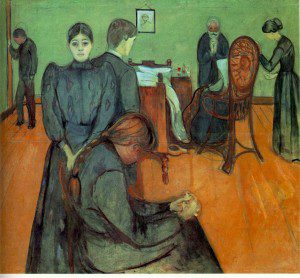

Birdman, thought I’d post some text from Becker’s introduction to Denial. By way of context, for Becker, human beings are deeply anxious creatures. Death is the root cause of our greatest anxiety. The existential recognition of our mortality terrifies us. What if we die–and that’s it? What if we die having left no meaning, no lasting legacy, no immortality?

The buffer against this anxiety, this terror of death, is self-esteem, or in Becker’s formulation of self-esteem, heroism. We undertake heroic projects (whether lofty and ambitious or modest and mundane) to create in ourselves a sense of lasting worth and value. Society itself, as Becker understood it, is a system of culture that facilitates the cultivation of self-esteem. This gives society (even purportedly “secular” societies) a “religious” dimension.

As he puts it,

The fact is that this is what society is and always has been: a symbolic action system, a structure of statuses and roles, customs and rules for behavior, designed to serve as a vehicle for earthly heroism. Each script is somewhat unique, each culture has a different hero system. What the anthropologists call “cultural relativity” is thus really the relativity of hero-systems the world over. But each cultural system is a dramatization of earthly heroics; each system cuts out roles for performances of various degrees of heroism: from the “high” heroism of a Churchill, a Mao, or a Buddha, to the “low” heroism of the coal minor, the peasant, the simple priest; the plain, everyday, earthly heroism wrought by gnarled working hands guiding a family through hunger and disease.

It doesn’t matter whether the cultural hero-system is frankly magical, religious, and primitive, or secular, scientific, and civilized. It is still a mythical hero-system in which people serve in order to earn a feeling of primary value, of cosmic specialness, of ultimate usefulness to creation, of unshakable meaning. They earn this feeling by carving out a place in nature, by building an edifice that reflects human value: a temple, a cathedral, a totem pole, a skyscraper, a family that spans three generations.

When Norman O. Brown said that Western society since Newton, no matter how scientific or secular it claims to be, is still as “religious” as any other, this is what he meant: “civilized” society is a hopeful belief and protest that science, money and goods make man count for more than any other animal. In this sense everything that man does is religious and heroic, and yet in danger of being fictitious and fallible. (pp. 4-5)

And then…

Society itself is a codified hero system, which means that society everywhere is a living myth of the significance of life, a defiant creation of meaning. Every society thus is a “religion” whether it thinks so or not…” (7)