Kelly Gissendaner was executed last night for her role in the murder of her husband in 1997.

Despite persistent appeals by her family and friends; despite public efforts by teachers and scholars in the prison theology program in which she participated; despite even an appeal by the Pope for stay of execution, the system moved heartlessly forward.

A increasingly critical eye is being cast upon the criminal justice system here in the U.S. More and more, people are talking about the problems with the system. The death penalty, with all its finality, represents the emotional height of the increasing restlessness with the justice system.

Is our criminal justice system really just?

What is justice, really?

Duncan Forrester dedicates a chapter in his book, Christian Faith and Public Policy, to “Punishments and Prisons.” He recounts his work serving on a committee exploring the problems with the prison system in Great Britain. He notes that, in Britain (as in the U.S.), the theoretical foundation under-girding the practices of criminal punishment had increasingly shifted away from a rehabilitation, or treatment, model toward a justice model.

A motivator of this shift had been a “feeling” that rehabilitation just doesn’t work. As he puts it,

Central is the feeling–and it is no more than a feeling–that rehabilitation doesn’t work. In general terms this means that systems that are, or that claim to be, based on rehabilitation or treatment do not seem to be any more successful in discouraging crime or recidivism than any other approach to punishment. Supporters of rehabilitation argue that it (like Christianity!) has never really been tried. It seems to be the case that it is almost impossible to find anything approaching a pure rehabilitation model in operation anywhere in Britain. (67).

I’m no expert on the criminal justice system in the U.S., but it seems to me the same thing can be said for us here: It is almost impossible to find anything approaching a pure rehabilitation model in operation anywhere in the U.S.

Part of the reason for this, Forrester suggests, is that a rehabilitation model requires the input of subjectivity in the system: “many people believe that rehabilitation is excessively arbitrary and discretionary…” Who decides what counts as rehabilitation for this particular prisoner and what are the criteria? Furthermore, to measure rehabilitation would require imposing a “particular view of human flourishing and the good without reference to the prisoners’ own goods and values” (68).

So rather than deal with the subjectivity or ambiguity or other potential difficulties with the rehabilitation model, the system has moved exclusively into a “justice model”; an approach which looks backwards on the crime committed and doles out a punishment that appears best to match the crime. It’s meant to be a purely economic measurement of sorts–attempting to eliminate subjectivity and to attain an objective system of “justice” for the sake of motivating others to avoid the same crime. You do this…you get that. The punishment must fit the crime.

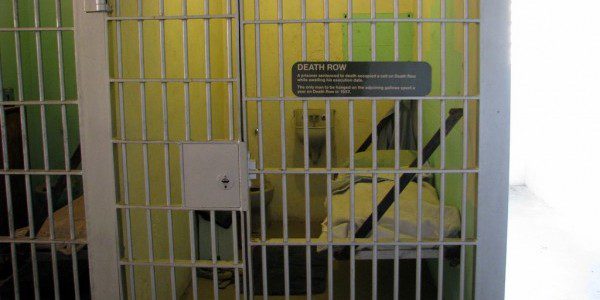

One of the many problems with this model, Forrester suggests, is that you end up with prisons as “human warehouses,” where people are simply stored, confined within walls, having no goal, purpose, or genuine community. It’s a fundamentally de-humanizing approach. Rehabilitation has gone out the window. He cites David Garland here:

We are developing an official criminology that fits our deeply divided, and increasingly anxious society. Unlike the rehabilitative welfare ideal which, for all its faults, was linked into a broader politics of social change and a certain vision of social justice, the new policies have no broader agenda, no strategy for progressive social change, no means for overcoming inequalities and social divisions. They are, instead, policies for managing the danger and policing the divisions created by a certain kind of social organization–and for preserving the political arrangements which lie at its center (70).

As I read the reflections on Kelly’s death, I see a mixture of anger, frustration, sadness, and even disbelief. How can someone who appears to be thoroughly rehabilitated, reformed, and so on, still have their life taken by the State? These are expressions of an intuitive sense that the death penalty is simply not humane. Perhaps it qualifies as “justice” under a very narrow, technical, economic definition of justice, but this is not the justice that we should want. It’s does not seem to be the kind of justice that we should want to organize our society around.

This narrow, technical, even heart-less sense of justice led to Kelly’s death last night. When the State puts someone to death for their crimes, they are either saying (1) they believe there is no hope for redemption, reconciliation, or rehabilitation or (2) that these things never really mattered in the first place.

That thin view of justice runs throughout the system. It might even be that injustice is a better descriptor. Whether private profiteering of criminalization, overcrowding, political corruption, or the very problematic racial disparity that runs throughout the criminal/prison system (that racial disparity, it should be noted, has been shown to be very much at work within our practice of capital punishment), we need to ask deeper questions as a society about what justice really is?

How might justice intersect with love, with reconciliation, and with redemption?