In Denial of Death, Ernest Becker argues (in chp. 4) that human character is a “vital lie.” He connects the development of what human beings call “character” to the necessity of psychological repression: living bluntly and truly honestly in the face of the mystery, power, and splendor of the world would be altogether too much for us.

We are too symbolic for our own good–too existentially “aware” of the ambiguous, fragile, and yet beautiful nature of existence and of our place in it. “Lower” animals, whose awareness of reality is much narrower than ours, can live more freely–in a sense–in that they react instinctively to events, stimuli, processes of nature.

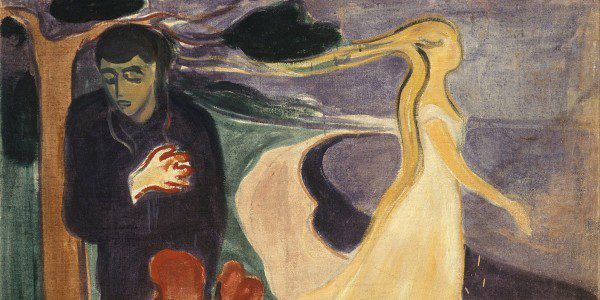

We, on the other hand, wrestle with anxiety and despair. And in the face of that anxiety–which can become utterly debilitating–we repress the sources of that anxiety and seek out activities that enable us to deal productively with it. We borrow power from our parental and cultural heroes, and we do the sorts of things that will enable us to fit into the system and to gain a sense of worth and well-being from the larger whole. We develop “character,”the “vital” (necessary) lie.

He writes,

In these ways, then, we understand that if the child were to give in to the overpowering character of reality and experience he would not be able to act with the kind of equanimity we need in our non-instinctive world. So one of the first things a child has to do is to learn to “abandon ecstasy,” to do without awe, to leave fear and trembling behind.

Only then can he act with a certain oblivious self-confidence, when he has naturalized his world. We say “naturalized” but we mean unnaturalized, falsified, with the truth obscured, the despair of the human condition hidden, a despair that the child glimpses in his night terrors and daytime phobias and neuroses.

This despair he avoids by building defenses; and these defenses allow him to feel a basic sense of self-worth, of meaningfulness, of power. They allow him to feel that he controls his life and his death that he really does live and act as a willful and free individual, that he has a unique and self-fashioned identity, that he is somebody–not just a trembling accident germinated on a hothouse planet that Carlyle for all time called a “hall of doom.” We called one’s life style a vital lie, and now we can understand better why we said it was vital: it is a necessary and basic dishonesty about oneself and one’s whole situation…

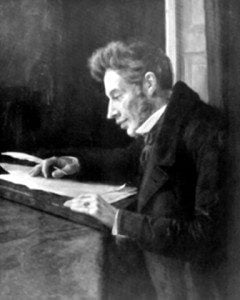

All of us are driven to be supported in a self-forgetful way, ignorant of what energies we really draw on, of the kind of lie we have fashioned in order to live securely and serenely. Augustine was a master analyst of this, as were Kierkegaard, Scheler, and Tillich in our day. They saw that man could strut and boast all he wanted, but that he really drew his “courage to be” from a god, a string of sexual conquests, a Big Brother, a flag, the proletariat, and the fetish of money and the size of a bank balance. (55-56)

…It is fateful and ironic how the lie we need in order to live dooms us to a life that is never really ours. (56)

Now, I have to admit here that this is the part of Becker that perplexes me the most. If character is armor against anxiety or debilitating despair in the face of the bigness and mystery of reality (and therefore a “lie”), then is the pursuit of virtue merely a self-interested mechanism for existing? Is morality a necessary, but specious, enterprise?

How would one teach a course like “Christian Ethics” under Becker’s shadow? It would certainly mean exposing rule-based theories of ethics as inadequate. It would also mean trying to bore down into the heart of the human person, exploring the ambiguous intersection between necessity (the vital lie) and authenticity. And, I would think, one would constantly ask the question, what gives life–both to the individual and to the community?

Finally: to be truly authentic (for Becker), would one need to shed one’s “god” entirely? Or is the implication (more satisfactorily) that one’s “god” can be a prop for existential defense just like any other prop (money, fame, sex, etc.) and therefore one’s god can easily become an idol?