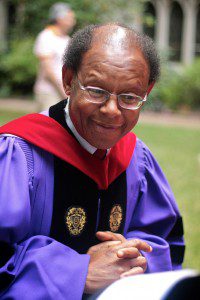

When I read James Cone’s God of the Oppressed eight or nine years ago, the significance of the contextuality of theology was deeply impressed upon me.

While I could not feel or know the power and passion of liberation theology from the perspective of one who was oppressed, I could feel the sting of critique against my own complicity in structures of oppression and my of my own ignorance in the ways that my

context blinded me to the severity and extent of oppression and marginalization–experienced by so many on the “outside” or “underside” of fundamental human rights, much less of society’s privileges.

To hear Cone say that “God is Black,” because God is on the side of the oppressed was a startling thing for me to hear. And yet it was necessary to awaken me from my blinders and my ignorance of the extent to which my own cultural/racial/socio-economic, etc. context shaped my own image of who God is (and of who God is not). I could not think of theology in the same light after that.

The following excerpt is from God of the Oppressed. This work, which followed both Black Theology and Black Power and A Black Theology of Liberation, stands as one of the most important books in contemporary theology–and may well go down as one of the most important books in the history theology, period.

In this section, Cone is addressing the “centrality of the New Testament’s emphasis on God’s liberation of the poor,” as a way of threading a line of continuity through the whole Bible, Old and New Testaments. And yet, with that continuity of emphasis, there was still a difference.

Cone sources the distinction in the person of Christ and the cross and resurrection; the distinction is a “new element,” of divine freedom breaking into history and also transcending it. In the Incarnation of God in Christ, divine freedom is made available for transformation, but a kind of freedom and transformation which is “not dependent on sociopolitical limitations..” He writes:

The cross and resurrection of Jesus stand at the center of the New Testament story, without which nothing is revealed that was not already known in the Old Testament. In the light of Jesus’ death and resurrection, his earthly life achieves a radical significance not otherwise possible. The cross-resurrection events mean that we now know that Jesus’ ministry with the poor and the wretched was God effecting the divine will to liberate the oppressed. The Jesus story is the poor person’s story, because God in Christ becomes poor and weak in order that the oppressed might become liberated from poverty and powerlessness. God becomes the victim in their place and thus transforms the condition of slavery into the battleground for the struggle of freedom. This is what Christ’s resurrection means. The oppressed are freed for struggle, for battle in the pursuit of humanity.

Jesus was not simply a nice fellow who happened to like the poor. Rather his actions have their origin in God’s eternal being. They represent a new vision of divine freedom, climaxed with the cross and the resurrection, wherein God breaks into history for the liberation of slaves from societal oppression. Jesus’ actions represent God’s will not to let his creation be destroyed by non-creative powers. The cross and the resurrection show that freedom promised is now fully available in Jesus Christ. This is the essence of the New Testament story without which Christian theology is impossible (73-74).