Albuquerque Police are reporting that a man named Tony Torrez, 32, has confessed to the murder of a 4-year old girl, Lilly Garcia, in a horrifying road-rage incident on an interstate in New Mexico. Torrez shot into the truck Lilly’s father, Alan Garcia, was driving, hitting and killing her.

Road rage incidents happen pretty regularly, it would seem, but typically end with a mutual flip of the bird (so I’ve heard) or some other relatively innocuous conclusion.

This morning, I picked up a hefty book by Darcia Narvaez, Neurobiology and the Development of Human Morality. It’s a book rich with detailed information on the implications of scientific knowledge of the inner workings of the human for better understanding how morality works–and how it develops in us over time, individually and socially.

I happened to flip to the chapter called “The Morality that Stress Promotes: Self-Protective Ethics.” Here she discussed in depth the concept of “safety ethics,” which has to do with the human instinct to follow “survival system instincts” and falling back into “self-protection,” thereby “overriding other considerations in social situations” (161).

When we feel like our safety is threatened, we can alter our way of thinking and “retreat from higher-order thinking” as well as disengage from typical social commitments (empathy, community, concern for the welfare of others, etc.). But the safety instinct is not just activated by fear and protection of one’s personal well-being; it can also be activated by a threat to one’s self-esteem (which can sometimes have the same net effect).

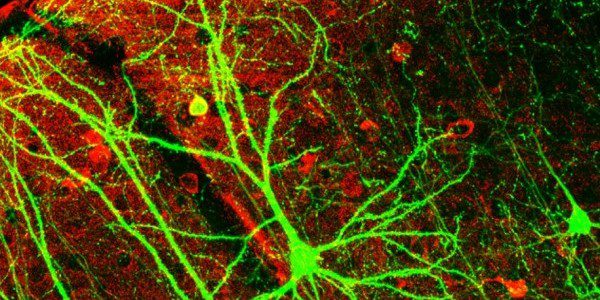

Biological/neurological systems are all in play here, but the point is that in high stress situations the higher-order ways those systems are organized and are supposed to function can be essentially abandoned. High stress and intense emotion can precipitate the abaondoment of those higher systems into a much more base and instinctual “self-protective” response.

Narvaez refers to another author, M. D. Lewis, who used a fictional character, “Mr. Smart,” to describe what was happening with road rage. In her summary, Narvaez writes,

Here we see that Mr. Smart’s frustration initially arose from the thwarting of a goal, perhaps mixed with fear from a close call, evoking a sense of helplessness and subsequent anger. While these emotions quickly formed, so did appraisals of the other driver as a rival or tormentor, or at least as someone blameworthy for obstructiveness (prior experience provided these filters for interpretation). An angry-anxious state stabilized and encouraged ruminations for revenge, while the stress response kept attention laser-focused on the offending individual. In such circumstances, if the offender makes a move perceived as a taunt, it can generate shame and reactive anger in Mr. Smart, arising from an appraisal of subjugation. All of this calls for an extreme action to save the image of the self from further humiliation. Thus, for Mr. Smart, previously rehearsed emotions of rage and shame and narratives of dominance and threat were enhanced by the stress response and the impairment of prefrontal capacities to control survival system emotions (159).

It’s worth noting (as I’m sure you, the reader, already have!) that the tragic and senseless murder in New Mexico can hardly be blamed on “the impairment of prefontal capacities.” The state will hold Tony Torrez, the whole person, accountable for the murder of Lilly Garcia, regardless of the extent to which we can understand what was going on–or not going on–in his neurobiological functioning.

Interestingly, Narvaez also mentions violent offenders whose crimes are not connected to any “real motive or apparent provocation.” These basis of their actions can be simply a perception (however false or true) that they were disrespected and a sense (however false or true) that their respect or dignity can be re-established by their violent action of retribution. Their “self-protective ethics” is not balanced out or moderated by “feelings of love, empathy, or guilt to inhibit it” (161).

But again, simply understanding the neurobiology involved in violence, rage, or whatever, is not to minimize or undercut the responsibility or moral culpability for those actions.

Her final paragraph in this section is instructive–and offers a ray of hope, too:

The road-rage example, like the violent criminal example, shows the downshift to self-protective morality as the survival systems take over the mind. The optimal functioning of our survival systems–i.e., under the control of the frontal lobe system so they are quickly snuffed out when real threat is not at hand–is vital for navigating the moral life. With maturation and intentional self-development, our deliberative capacities, including moral self-reflection and development of new habits, allows us to shift the pathway we are on (e.g. toward a particular goal) and change course (161).