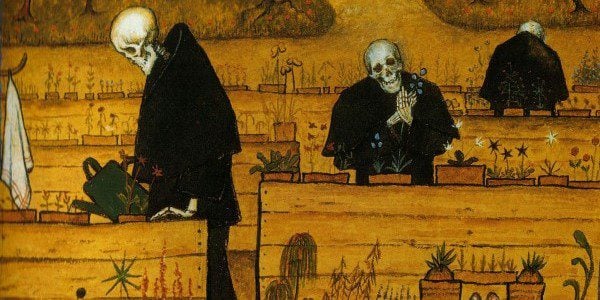

This semester I’ve been teaching a course called, Death, Evil, and Alienation here at United Seminary. It’s not as depressing as it sounds. Well, OK, sometimes it is. We’ve certainly seen a lot of tragedy and terror over the past several months.

Throughout the semester, along with the challenging texts we’ve read, we’ve also had a steady supply of examples of these phenomena (death, evil, alienation) on the national and international scale.

Obviously ISIS has been a big topic of conversation–as has terrorism of all sorts (including both Islamic and Christian). The Paris attacks and now recently the San Bernardino massacre has figured heavily into discussion.

The centerpiece for our theoretical engagement with these phenomena has been Ernest Becker’s The Denial of Death. We’ve also used the excellent book, Worm at the Core, by a triad of “Terror Management Theory” psychologists, who put Becker’s theory to the empirical test–and who thereby showed the viability of his theories.

Becker’s themes have been a constant reference point in our attempt–limited though it is–to understand the link between the brute fact of the inevitability of death, our conscious and subconscious awareness of our mortality, and the evil and alienation bubbling around us and the terror (of death) that rumbles within.

In a recent paper, a student cited another of Becker’s texts, Escape from Evil. In his chapter on the “Nature of Social Evil,” Becker reflects on what he calls the “logic of killing others.” He references the Roman gladiator games as an example of the ways in which, throughout so much of history, killing other human beings provides some (temporary) alleviation of one’s own anxieties about their inevitable death. Killing others gives us a sense that we will not be killed–at least, not yet–and lures the killers to imagine themselves as impervious to death. Becker writes,

It is obvious that man kills to cleanse the earth of tainted ones, and that is what victory means and how it commemorates his life and power: man is bloodthirsty to ward off the flow of his own blood. And it seems further, out of the war experiences of recent times, when man sees that he is trapped and excluded from longer earthly duration, he says, “If I can’t have it, then neither can you.” (111).

Other things that we have found hard to understand have been hatreds and feuds between tribes and families, and continual butchery practiced for what seemed petty, prideful motives of personal honor and revenge. But the idea of sacrifice as self-preservation explains these very directly. As [Otto] Rank saw, the the characteristic of primitives and of family groups was that they represented a sort of soul pool of immortality-substance. If you depleted this pool by one member, you yourself became more mortal. (112)

To feel protected against death, you need to feel that your tribe is stronger than the competitor. A death in your tribe at the hands of the enemy is a chink in your (collective) psychological armor. Something like this phenomena still explains so much of the violence of the modern era, Becker suggests, in the way people of one “tribe” or group (whether national or religious) relate to persons of another group. As he writes,

We couldn’t understand the obsessive development of nationalism in our time–the fantastic bitterness between nations, the unquestioned loyalty to one’s own, the consuming wars fought in the name of the fatherland or the motherland–unless we saw it in this light. “Our nation” and its “allies” represent those who qualify for eternal survival; we are the “chosen people.” From the time when the Athenians exterminated the Melians because they would not ally with them in war to the modern extermination of the Vietnamese, the dynamic has been the same: all those who join together under one banner are alike and so qualify for the privilege of immortality; all those who are different and outside that banner are excluded from the blessings of eternity. The vicious sadism of war is not only a testing of God’s favor to our side, it is also a proof that the enemy is mortal: “Look how we kill him.”

In the aftermath of terrorism, murder, genocide, and so on, we often call it “senseless violence.” We think it is senseless in that it surely didn’t have to happen. But seen from another angle, it is not “senseless,” in that there are reasons for it.

Perhaps there is even a “logic” to such violence, as Becker helps us to see. But it’s a logic that must be overcome and undone by a different way of living together, by a better way of being human.