Looking at what so often goes by the name “evangelical” or “evangelicalism” today, you would assume that evangelicals were always resistant to women at the highest levels of church leadership and public ministry roles–certainly in its origins.

I mean, there may be some progressive, egalitarian, feminist evangelicals today–but centuries ago? Surely not.

But you would be wrong.

Evangelicalism in America mainly sprang out of the soil of eighteenth and (perhaps especially) nineteenth-century American revivalism. And that nineteenth-century revivalism was in many cases quite progressive on several key social issues–one of which was the role of women in leadership.

Doug Sweeney, in his meaty little book, The American Evangelical Story, describes the development of early evangelical revivalism into sustainable, thriving institutions–many of which were either evangelistic, educational, or social service-related. Numerous women were involved in these institutions, and many of them in public roles as preachers. He writes:

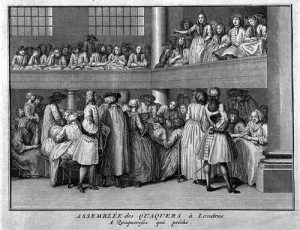

A surprising number of women had served as preachers, teachers, and evangelists during the century or so that followed the birth of the evangelical movement. Several hundred women, in fact, preached in the time between the Awakenings [the first and second “Great Awakenings,” revival movements that resulted in numerous

new converts, changed lives, and which spawned many new social change efforts], though most of them came from sectarian groups like the Quakers (technically known as the Society of Friends) and Free Will Baptists. (75).

Historian Donald Dayton presses the point much further, including in his (revised) book Rediscovering an Evangelical Heritage, a chapter called “The Evangelical Roots of Feminism.”

In that chapter he quotes Beverly Wildung Harrison (Union Theological Seminary) who makes this startling claim–well, startling for those who aren’t aware of the roots of evangelicalism in nineteenth-century revivalism:

The fact is that the social origins of the woman’s rights movement in America will not be fully or adequately understood, nor the early feminists rightly appreciated, until the connection is duly acknowledged between the woman movement and left-wing Reformation evangelicalism in America. (cited on p. 136 in Dayton)

Dayton goes on to note,

Actually, it is evangelicalism that next to Quakerism has given the greatest role to women in the life of the church. This practice crested in nineteenth-century American revivalism but was foreshadowed in the Evangelical Revival of the preceding century.

The egalitarian, feminist impulse in early evangelicalism was due in part to what Dayton describes as the “leveling force in vital evangelical religion.” Charles Finney and other revival preachers were convinced of the universality of sin and of the universality of access to grace.

This universality is the key to the “leveling force,” because it means that everyone, male or female, black or white, rich or poor, slave or free–are ultimately in the same situation: needing God’s grace and having the opportunity to accept it. For this reason, Finney and other early evangelicals were also key influencers of the anti-slavery, abolitionist movement.

The “innovative and experimental” aspect of early evangelicalism was also a key reason for the egalitarian impulse, creating a culture ripe for breaking new ground (including “new measures” such as women preaching, praying in public services, leading, etc.). He explains:

In this way evangelicals began to experiment with new roles for women in the church. Wesley himself gave approval to a few women preachers by the end of his life. And in America the Great Awakenings reproduced the same phenomena that by the end of the eighteenth century women preachers had begun to appear in such groups as the Freewill Baptists. Evangelicals did not continue in these practices without testing them against scriptural exegesis, but they found that by approaching the Scriptures with unbiased eyes it became clear that women had played a more significant role than had previously been assumed, and that a biblical case could be made for giving them more responsibilities in the contemporary church (137-138).

This is why the continued resistance to women in public, church ministry by many self-described evangelicals in the United States today is hardly legitimate–certainly non the basis of the “evangelical roots of feminism” in its origins.