The following is a guest post by Silas Morgan. Silas earned his PhD from the Department of Theology at Loyola University in Chicago, Illinois. He is the managing editor at Syndicate Theology and adjunct faculty at Hamline University in St. Paul, MN. He kindly gave me permission to re-post an abridged version of his “letter to his Christian Ethics students.”

A letter to my students

Christian ethics after Trump

“The greatest danger to Christianity is, I contend, not heresies, not heterodoxies, not atheists, not profane secularism – no, but the kind of orthodoxy which is cordial, drivel, mediocrity served up sweet. There is nothing that so insidiously displaces the majestic as cordiality.” – Søren Kierkegaard

We have spent a fair amount of time in this course so far trying to understand social problems. So much disagreement, so much conflict, so many of the obstacles to social change (something that most of all agree we need, even if we disagree how or why or what) come from differences in how we as social agents – persons who act in society and in support of a particular perspective on what we want society to look like – understand “what is going on” in social problems.

I have suggested that the best way to understand social action is to see it in at least three parts/steps: (a) understand social reality (“what is going on?”), (b) interpret social reality (“what does it mean?”) and (c) engage social reality (“what should we do?”).

Another point that I have tried to make about the first two – understanding and interpretation – is that social problems are not simply products of individual actions (the “bad apple” theory) or wrong beliefs, but instead are problems with the systems and institutions that structure and govern human behavior – they reside within our normative standards and our prevailing cultural attitudes. Being able to properly identify what the problem is and where the problem resides within social reality is only the beginning – one must then begin to figure out how best to oppose it, how best to correct it, how best to offer alternatives.

Take torture. Simply saying “torture is bad” is not going to effectively end torture. Torture is made possible because of social reality in which torture works, in which it has an effect, in which it makes sense. Take racism. Simply saying “racism is bad” is not going to end racism. Racism is made possible because of social reality in which racism works, in which it has an effect, in which it makes sense. The only way to end racism is to bring an end to the conditions in which racism works.

Many of you have said you think that that is impossible, that it will always be with us, and that best we can do is try to change people’s minds about others. I understand that and I feel myself as if that’s true at times. But then I think of those who continue to suffer under racist and xenophobic conditions, who feel fear and hopelessness because of hate and bias, and then I am reminded how important it is to say that Christianity, I believe, demands more from us.

Let me table that question, just for a moment, because there is something that we need to talk about first.

On Tuesday night, Donald Trump was elected President of the United States. At around 10pm, when it was clear that the night was going well for him and that he was likely to win, I thought first of you – my students. What do I tell them? I want to acknowledge of course that there are many different perspectives in this room – and that no one ought to be shamed for their political choice.

It is possible some of you – the breakdowns indicate that perhaps many of you – voted for Trump and you have many reasons for doing so. My point here is not to make comments on the ethics of that political choice or pass judgement on it. But what I feel is essential to do in this moment is to comment on the consequences of that political choice, and to talk briefly about what role Christians and their communities ought to have in the days, months, and years ahead – specifically the role that Christian ethics can play in shaping how and why communities of faith resist and how they care and advocate for their neighbors. How does Christian ethics shape how Christians ought to respond and engage a social and political context in which Trump has power and his policies hold sway? And again, let be clear – there will be those who disagree with me about this. I welcome your push back; one of the most important things over the next period in our social and political life is that we will have to get better at talking to those with whom we do not agree. It will not be fun; it will not be easy, but it’s essential.

Elections have consequences. Everyone is basically agreed that the unknown and unpredictable character of Trump, his interests, and his commitments made it nearly impossible to predict what he will do and what effect it will have. But Trump has been in our political world a long time and in our social consciousness even longer – and he represents a series of sentiments and values that have proven hard to extract from our cultural landscape.

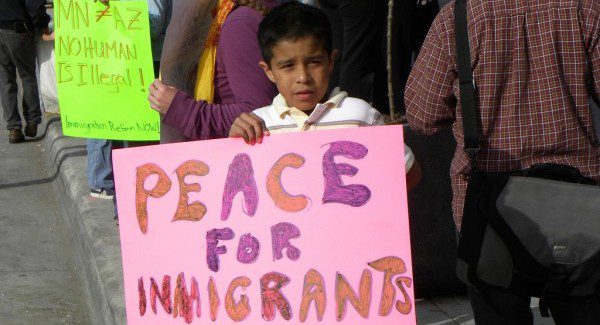

I just want to be clear about something. If we are going to be able to talk about social reality as it is, we will need to work hard to get facts straight. Let us get beyond political talk here and just talk about facts: Fact(s): Trump believes in torture; he says “it works.” Trump has argued for a religious test for immigration – he wants to ban all Muslim persons from immigrating to the United States. He has been endorsed by the KKK and other white nationalist groups who believe that he will champion their causes. Trump wants more nuclear weapons in the world, not less, and has openly talked about using nuclear weapons. Trump wants to end abortion rights for women, a constitutionally protected practice – and that women who receive abortions should be punished. Trump wants to repeal the Affordable Care Act, which means that millions of poor, working class Americans will no longer have access to quality, affordable health care. Trump opposes marriage equality and would work to sign legislation banning same sex marriage. These are facts, policy positions that he has detailed over and over and over again.

But let me be equally clear about something else: I do not believe Christianity is neutral about this. Any account of Christian ethics that you may find that supports this position stands in sharp contrast to that which Jesus sets forth in the gospels. This is the frontline of the struggle to come – a struggle within Christianity about two very different visions of the world and understandings of the Christian moral imagination.

I believe that Christianity offers an alternative vision of the world, its claims to radical equality, its openness to the foreigner, the stranger, the religious or ethnic other, its unrelenting opposition to war and violence in all its forms, its inclusivity, its commandment to love your enemy even at cost to yourself and your own interests, its stubborn hope that the world as it now will pass away, and a new one will come – a world of a lasting and enduring peace borne out of justice, not silence.

The moral beliefs that support Christian ethical commitments (love, justice, and solidarity) are not neutral, they are not impartial, they are not for everyone. This is why they are often suppressed, neglected, overlooked, and at times opposed by Christian communities themselves, communities which for one reason or another want something else. Love, justice, and solidarity are not empty, broad categories that can mean anything to anyone. So what do they mean in this context – what does Christian ethics mean for a world where the most powerful man in the world is Trump?

The history of Christianity details its on-again, off-again relationship to power. Christianity – build upon the teachings of Jesus Christ whose death by crucifixion was that of a political criminal, an insurrectionist who was executed by the Roman imperial forces because of the perceived threat that he was to the empire – was not meant to be close to power. It has tried at times to do so – we are in one of those times – times when being close to those who have power, being cozy with powerful interests is seen as a way to gain access to power so as to accomplish its agenda.

The problem with this is that it has little resonance with biblical Christianity. It does not fit with the politics of Jesus. Jesus’ teachings call for a dismantling of system of power; it promises a radical reversal, an upside down society, in which those who have power will have none, and those who are powerless, who are poor, who mourn, who are hungry, who are despised and persecuted, demeaned and demonized – they will receive justice. God stands in solidarity with their suffering – and calls the church to join her in that work. If you suffer, if you are vulnerable, if you are hated or despised by those around, the Christian God says to you, I am with you.

I want to say to you, as a professor, and as a scholar, – that I welcome you, that you belong here, both in this community and in this society. I want to say to you that I love you. I love you if you are Muslim, if you are queer, if you are Latino/a, if you are a survivor of sexual violence, I love you if you are disabled, I love you if you are poor. That love is a political love, it forces me to make choices, choices to speak up when I don’t want to; to act in ways that are professionally risky, unpopular, and hard; it is love that shapes my work, what and how I teach, the choices I make daily; it shapes the way I will work hard to raise my son. I will fight for you, no matter what. And I will work hard to tear down the walls built by hate, by misunderstanding, by ignorance, and by fear. I have been taught to do this by Jesus, who made clear what the criteria are for a society that honors God’s justice. I give you Matthew 25:

“When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will put the sheep at his right hand and the goats at the left. Then the king will say to those at his right hand, ‘Come, you that are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.’Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry and gave you food, or thirsty and gave you something to drink? And when was it that we saw you a stranger and welcomed you, or naked and gave you clothing? And when was it that we saw you sick or in prison and visited you?’ And the king will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.’ Then he will say to those at his left hand, ‘You that are accursed, depart from me… for I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not welcome me, naked and you did not give me clothing, sick and in prison and you did not visit me.’ Then they also will answer, ‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or sick or in prison, and did not take care of you?’ Then he will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me.’

And so – in what ways does Christian theology and ethics shape the way forward for us all? And to be clear, this is not simply a matter for those who disagree with Trump or oppose his positions, but something that we will all need to work towards.

1. We have to get beyond our fear of each other. Some things must matter more than our worries of being offensive or being offended, than our rather selfish desire to get just along. The stakes are too high to simply be complacent because the alternatives are difficult or uncomfortable. Jesus joins the biblical prophets in decisively opposing indifference and silence when faced with injustice. We need to toughen up, to learn how to be honest and authentic; we need to become more comfortable with the tension and awkwardness that comes with disagreement and learn how to care for each other – especially those we oppose, those that stand on the other side – even while we struggle against them.

2. We must learn empathy. We must practice – we must get good at – listening to each other, learning from the other – not with the empty goal of finding “common ground” (which often just covers over differences instead of embracing them – and more often or not just supports the dominant status quo rather than challenging it), but coming to terms with the other and their particulars (especially those that make us uncomfortable, that confuse, threaten, or otherwise trouble us).

3. We must learn to live like we belong to each other – like we are responsible for each other. What would life look like if I truly believe that my well-being, my interests, my hope for the future is wrapped up in yours? We must reject individualism – the belief that we are fully autonomous, detached from each other, and in control of our own futures apart from the future of the other. We must oppose the power of self-interest and be willing to call for a social order that recognizes that when one of us falls behind, we all do and that none of us can who we were created to be if not all of us are given the dignity and freedom of a life that is livable, a death that is grieved, and a body that is recognized.

4. We must rediscover the beauty of interdependence – the fact that we are mutually constituted, that I cannot be who I am without you, that I am not in full control of myself, but am always set up, grounded, gripped by you and our relationship. This is a very anxious truth because it counters that myth that I am only responsible for myself, that I can only worry about myself. We are all bound up together and so have the power to undo each other; just as we have the power to rip each other apart, we have the capacity to secure each other, to give each other intelligibility, to make it possible for each other to hear and to be heard. We have great power – we have the ability to both crush each other and build each other up. With great power, comes great responsibility. What would our social world look like if we took that responsibility seriously?

What will do you do now? What must be done in order to secure civil rights for your neighbors, protect the vulnerable, and fight against all forms of social evil: hate, fear, vengeance, bigotry, exclusion? What will you do to care for yourself, to prepare yourself to resist and struggle against forces that seem eager to make your life difficult, to make you feel unwanted and unvalued, that make you cheap everyone?

How will you posture yourself to understand one another, to show kindness, and stand up for each other, amid these differences?

—

I had always planned today to talk about resistance. What is the role of resistance to power in Christian ethics? How does Christian ethics shape how Christians are to act when resisting social injustice, moral evil, systemic oppression? What are some principles that ought to shape the tactics Christians use in social action to resist forces and practices, belief and attitudes they consider to be antithetical to the moral convictions of their faith? More concretely – for Christians (whether they voted for Trump or not) how they are to resist, disrupt, or otherwise dissent with polices and politics set forth now in our social world? What tactics are acceptable, given Christian commitments to love and nonviolence, and what strategies are most effective when facing systemic problem. One point I have tried to make over and over again is that the problems we face are not problems with individuals who have wrong or false beliefs and so do bad things, but rather with systems, structures, and institutions that are sinful, that are oppressive, and so form us to believe things about our neighbors that aren’t true, to act in ways that violate Christian commitments to human dignity and equality and justice, and keep us from actively opposing the evil we see in the world, either through indifference, compliance, confusion, or fatigue.

What examples do we have to help guide and lead us? We will discuss two models for dissent and resistance: (a) MLK’s discussion of rioting during the Civil Rights era and (b) Osterweil’s defense of early black protests against police violence. We turn to these examples because they help us raise important questions about how does one actually oppose sinful systems and unjust institutions? What must be done – not just said – to disrupt patterns and beliefs that do harm to others, that fuel hate and distrust and fear? What tactics are necessary and which ones are right? How does Christian ethics shape the ways we should resist the structural evil that leads to our social problems?

Silas Morgan earned his PhD from the Department of Theology at Loyola University in Chicago, Illinois. He currently lives in Minneapolis, MN with his lovely wife, Laura, and darling son, Elliott. He is the managing editor at Syndicate Theology and adjunct faculty at Hamline University in St. Paul, MN. His dissertation studied the relation of theology to ideology in political theology, with close intersectional analysis from both critical theory and continental philosophy. Future publications include a co-authored monograph, Alienation: A Materialist Theology (with Kyle A. Roberts), a co-edited multi-author volume, Søren Kierkegaard and Political Theology (with Roberto Sirvent), and an introduction to Slavoj Žižek’s political theology.

Silas Morgan earned his PhD from the Department of Theology at Loyola University in Chicago, Illinois. He currently lives in Minneapolis, MN with his lovely wife, Laura, and darling son, Elliott. He is the managing editor at Syndicate Theology and adjunct faculty at Hamline University in St. Paul, MN. His dissertation studied the relation of theology to ideology in political theology, with close intersectional analysis from both critical theory and continental philosophy. Future publications include a co-authored monograph, Alienation: A Materialist Theology (with Kyle A. Roberts), a co-edited multi-author volume, Søren Kierkegaard and Political Theology (with Roberto Sirvent), and an introduction to Slavoj Žižek’s political theology.