A few weeks ago I went to see Silence, the Scorcese film (based on the novel by Shushaku Endo) about Portuguese Jesuit missionaries in Japan during a period when Japanese Christians faced martyrdom for converting.

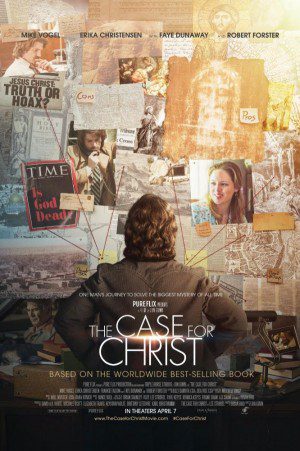

During the previews, I was startled out of my comfortable seat by a preview of an upcoming film called The Case for Christ. For anyone who might not recognize the title (which is to say anyone who didn’t grow up evangelical Christian in the 80s or 90s), The Case for Christ is a widely-read book of Christian apologetics by Lee Strobel.

Somewhere, somebody thought making a film based one The Case for Christ is a good idea. But why?

Strobel, in his early days, was a legal journalist for the Chicago Tribune and an avowed atheist who set about to use his journalistic tools and legal mind to disprove Christianity before the court of Reason, only to discover that the “case for Christ” — including the historicity of the resurrection — is actually a slam-dunk in the other direction.

For Strobel (as for many other evangelical apologists of his ilk), if you neutrally but honestly apply the rigors of historical skepticism and journalistic investigation into the question of Jesus’ historicity and the integrity of the gospels, you end up with an epistemologically-confident conclusion: the New Testament is objectively, demonstrably true, and therefore Christianity must be the one, true, right religion.

When an “award-winning” atheist journalist sets out to disprove Christianity once and for all, and he winds up a convinced, faithful Christian believer — case closed!

When I taught theology at an evangelical seminary, a number of students came in with Strobel’s book as their basic road map to how they approached the Bible and theology (and a number of my colleagues shared this approach). Some of them (by no means all) distrusted any talk of subjectivity and “contexuality” or “perspectivalism” and “epistemological fallibility.”

They viewed Christianity primarily as a system of beliefs which were “objectively true,” and which were founded on an inerrant Bible (filled with universally true propositions). Of course they believed that Christianity, while being objectively true, also has subjective application. It makes a difference in life and of course in terms of one’s eternal destination.

That caveat aside, the presumed objectivity (rationality, neutral investigation) of Christianity seemed to take a privileged place over the subjective dimensions — if not in lifestyle and practice, certainly in theology.

I had – and still continue to have (though in a moderated form) – a different bent.

I’ve been drawn to approaches to theology and accounts of religion that don’t so sharply distinguish the “objective” from the “subjective.”

Kierkegaard has been my main influence in this regard. For Kierkegaard, when it comes to matters of existential and religious significance, it’s the “how” and not the “what” that should most pique our interest. While he believed that there are some basic “facts” of Christianity, and that Christian religion — like any religion — certainly can be viewed from an objective standpoint, to do so primarily is to diminish the role of faith in favor of prioritizing reason. Furthermore, objective approaches to religion can be ways of avoiding their existential import.

For example, to rely on a doctrine of inerrancy as a foundation for Christian faith and practice is to undercut the dynamic nature of one’s relation to God. The enterprise of Christian apologetics, for Kierkegaard, is wrongheaded in that it promotes an objective approach to religion rather than a subjective one, thereby dichotomizing reason and passion, text and appropriation of text, and prioritizing a supposed or presumed neutrality over the deep concern of faith.

We can find something of a precursor to a Kierkegaard’s approach in the Anglo-Catholic man of letters, Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

James Livingston, in his history of Christian thought, explains:

For Coleridge, metaphysical truths are never discerned by the speculative or discursive reason alone but by the whole person, which includes deep feeling and willing. The apprehension of spiritual truth involves the emancipation of the soul from the “debasing slavery to the outward senses” and the “awakening of the mind” to the true criteria of reality, namely, permanence, power, will manifested in act, and truth operating as life.” Thus Coleridge looked with particular horror on the many books purporting to “prove” Christianity by discursive reason alone.

And then from Coleridge himself:

I more than fear the prevailing taste for books of natural theology, physico-theology, demonstrations of God from Nature, evidences of Christianity, and the like. Evidences of Christianity! I am weary of the word. Make a man feel the want of it; rouse him, if you can, to the self-knowledge of his need of it; and you may safely trust it to its own evidence remembering only the express declaration of Christ himself: No man cometh to me, unless the Father leadeth him.

And then Livingston again:

In Coleridge’s view Christianity is not essentially a set of doctrines but a way of life (sounds a lot like Kierkegaard, there). The proper approach to the honest doubter, then, is not to seek to resolve his or her speculative difficulties but to call upon the person to “Try it!” The proof is found in the practice. (89)

All that said, I do appreciate the employment of reason, history, science (these “objective” methods) in theology – whether this is done by evangelical apologists or liberal theologians. I’ve grown to appreciate, more than in my earlier, more evangelical days, the importance of scientific and rigorously historical approaches to religion.

But I suspect that, in cases like “The Case for Christ,” there is as much emotion, existential import, contextual concerns, and other matters of subjectivity, driving the supposedly neutral or objective approach than meets the eye . Perhaps it would be more intellectually honest to admit the role of subjective and pragmatic concerns in these kinds of apologetic pursuits?

But more to the point, I think that conservative apologetic approaches too often ignore or paper over real problems, contradictions, in the haste to and pronounce that the “case is closed.” Their haste might come from well-meaning and even sincere motivations, but the end result is that too many of their disciples are led to believe they have epistemological, theological, and religious right of way in a network of roads which is too complex to legitimately make such pronouncements.

And too often, the result is theology and belief that is too superficial to hold up to more serious intellectual challenges.

I bristle at another “God’s Not Dead” type movie, charging hard at a culture for whom dogmatic, exclusivistic, and certainty-laden forms of religion contributes negatively to our larger situation.