Dorothy Sölle (1929-2003) might be one of the best theologians you’ve never heard of.

In Thinking About God: An Introduction to Theology (which I’ll be using as a text this fall for a course on Theological and Religious Interpretation at United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities, Sölle offers a succinct and powerful description of the task of feminist theology–and of the possibility of critically and respectfully engaging the Bible and Christian tradition with the goal of recovering their usefulness for social justice and humanitarianism–what she calls the “liberating character of the Bible.”

Here’s a selection from that chapter:

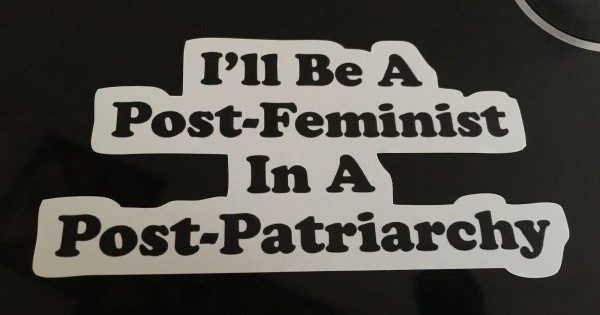

Some women have concluded from the great difficulty that the document to which Christianity refers, namely the Bible, is a patriarchal document, that they should put this document aside and depart from this tradition. Here I am referring to the post-Christian wing of feminist theology which is breaking away from the Bible. The most important representative of this line is Mary Daly, who has left the Catholic Church and broken with Christianity because she regards it as hopelessly, unchangeably patriarchal. Others, who in West Germany include Luise Schotroff and myself, represent a more moderate Reformation wing. We too see that the Bible is an androcentric and patriachal document, but at the same time we discover in it a fundamental opposition to these traditions; we read it as a book of justice, aimed at liberation from all the bonds that enslave us…We are attempting to work out the contradiction within the biblical traditions more clearly and to bring them to consciousness, so that we do not have to leave the house of the church; but we want to purge it of the traces of patriarchy.

The position of feminist liberation theology does not amount to exodus, to departure, to celebrating the goddess, but is concerned to remain true to the Godhead (to use a term from Meister Eckart) of the tradition, so that its justice ultimately becomes visible as a humanitarian one.

And a little later on, she observes:

But my personal experience is that my confidence has grown through work on the liberating character of the Bible, and my hope in God as the God of justice, which I understand also to mean sexual justice, has grown through intensive critical attention to the Bible. And that has happened precisely when I have had to criticize particular parts of the tradition radically.

And then, the kicker:

Work in the liberation movements for peace and reconciliation with creation have made me more hungry for a good use of the tradition. It has relieved me of my biblical relativism suggested by the Western culture deriving from the Enlightenment and has grounded me more deeply in the human traditions of the Bible. I do not feel excluded or homeless as a woman, and I think that an increasing number of women feel the same. It is not we feminist theologians who betrayed the tradition with our criticism of the personal and institutional sexism of the church when we began the exodus from the hierarchical and patriarchal culture of Egypt, but that part of the male church which continues to identify the Golden Calf of capital, violence and phallic power with God (75).