One of the first things you learn in seminary–assuming you pay attention–is that all translations are interpretations.

There’s no better illustration of that than what we find in Peter Marshall’s impressive tome, Heretics and Believers: A History of the English Reformation.

As the 500 year anniversary of the Reformation approaches, we here all sorts of things about Luther and the 95 theses. But what sometimes gets overlooked is the role that Bible translations–both pre-Luther (Wyclife) and during Luther’s time (Tyndale)–played in setting the stage for the Protestant Reformation and in catapulting it to a world-changing movement.

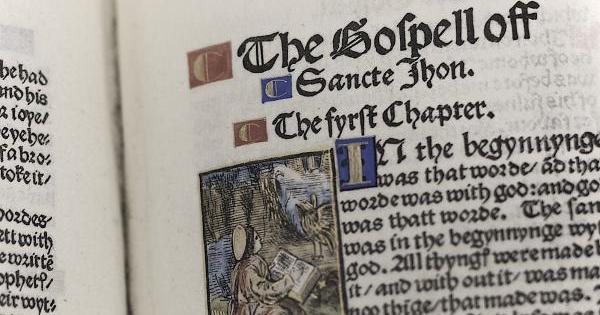

One of the key figures in that was the English priest and scholar, William Tyndale. His translation of the New Testament into English provided plenty of fuel for the fire for those who wanted to challenge Roman Catholicism in England and elsewhere.

Here’s Marshall, describing Tyndale’s provocative and controversial translation choices: (“translation is interpretation”):

Several choices in particular outraged Tyndale’s critics, confirming the opinion that what was being smuggled into England was not the New Testament of Christ, but a pernicious mockery of it–‘Tyndale’s Testament’ or ‘Luther’s Testament.’ By rendering the Greek word charis (gratia in the Vulgate), as ‘favour’ not ‘grace,’ Tyndale downplayed the importance of grace-giving sacraments. Making agape into ‘love’ rather than ‘charity’ (caritas) shifted focus away from acts of charity–good works.

Other translations hit directly at structures of ecclesiastical authority. Presbyteros, a term of early Christian leadership, was transliterated as presbyter in the Vulgate, and gave rise to the English word ‘priest.’ Tyndale initially had it as ‘senior,’ subsequently changed to the less foreign-sounding ‘elder.’ Ekklesia (Latin, ecclesia; English, church) became ‘congregation.’ Most crucially, the Greek verb  metanoeite was rendered as ‘repent’, instead of, as the Vulgate had it, ‘do penance’ (poenitentiam agite). It signalled an interior turning to God in the heart, rather than restorative action through the sacrament of confession. In an angry and alarmist letter of February 1527, Tunstall’s chaplain Robert Ridley protested to Warham’s chaplain Henry Gold that ‘by this translation, shall we lose all these Christian words: penance, charity, confession, grace, priest, church.’ The interlocking elements of an entire framework of faith and practice were being recklessly unscrewed and discarded.

metanoeite was rendered as ‘repent’, instead of, as the Vulgate had it, ‘do penance’ (poenitentiam agite). It signalled an interior turning to God in the heart, rather than restorative action through the sacrament of confession. In an angry and alarmist letter of February 1527, Tunstall’s chaplain Robert Ridley protested to Warham’s chaplain Henry Gold that ‘by this translation, shall we lose all these Christian words: penance, charity, confession, grace, priest, church.’ The interlocking elements of an entire framework of faith and practice were being recklessly unscrewed and discarded.

Interpretation is translation. And, interpretation is theology and (very often) politics, too!