Most of us don’t want this life to be all there is. We don’t want it all to end with a funeral. Most of us want something “more.” But what’s the “more” that we want?

Is it enough to know that we “live on” through the memories of our friends, loved ones, and other people we’ve influenced or touched in some way? Is it enough to be remembered?

Or, do we need/want to believe that we’ll have some kind of life (consciousness, agency, will, emotion, etc.) that goes on after we die? Does a satisfactory sense of immortality require the continuation of real life, genuine relationships, perhaps even (as in the later Judaic and Christian traditions) with real, tangible, bodies?

We had a great discussion of this question in my “Immortality and Hope” class last week at United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities.

It’s also a question raised, brilliantly, by Morgan Freeman in the first episode (airing last night) of his National Geographic documentary, The Story of God.

Freeman travels to important religious sites across the globe (last night’s stops included Egypt, Jerusalem, India (Varanasi), and New York (with a fascinating glimpse into some high-priced technological attempts to extend “life” beyond death).

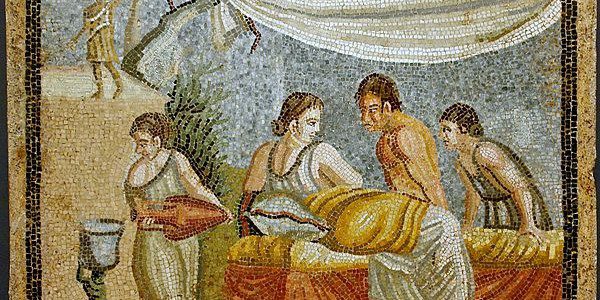

During his first stop, the pyramids of Egypt, Freeman’s archeological guide shows us how some of the earliest known afterlife beliefs developed. Egyptian kings didn’t want their lives to end at death (most of us don’t!), so they had stories about their lives and conquests inscribed into the walls of their tombs and pyramids. And they had their names inscribed, over and again, to be sure that endless generations after them would know their names and would repeat their names out loud. Every time their name was stated, they “lived on,” but not just through memory, but through a kind of mystical re-actualization of their self through their name being spoken.

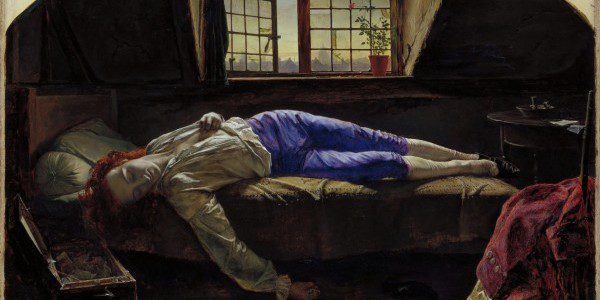

Robert Jay Lifton, begins his important book, The Broken Connection, by sketching out various ways that people attempt to overcome their fear of death and to deal psychologically and emotionally with the knowledge of their eventual and inevitable annihilation. He argues that beliefs about immortality developed in large part to overcome the otherwise psychologically debilitating knowledge of the brevity of life

Lifton distinguishes two basic categories of immortality beliefs: (1) literal immortality beliefs and (2) symbolic immortality beliefs. Literal immortality beliefs are beliefs in some kind of tangible, “real,” enduring (usually everlasting) life after death. The person truly “lives” on after death, whether through reincarnation, resurrection, or some other means of post-death life.

Symbolic immortality beliefs are as much practices as they are beliefs. They are often more implicit than explicit. Attempting to secure one’s legacy is a form of symbolic immortality. Creating cultural products (whether through science or art) that have lasting value and use, that make a lasting impression is symbolic immortality. Being a part of something greater than oneself–gives a sense of transcendence and meaning that overcomes the sting of the annihilation of self which comes from death.

And of course, “Being remembered” is form of symbolic immortality.

But we’re back to our original question: Is “being remembered” enough?

When I think of the powerful Egyptian kings, ordering their slaves to inscribe their names repeatedly on the walls around their tombs or on those pyramids, I think about the reality of our world which is that some have the power, whether through wealth, talent, or luck, to write their names very large and very often on the cultural artifacts of history. They have the power to create a symbolic immortality for themselves.

Of course, for these Egyptian rulers, symbolic and literal immortality intersected. It’s impossible to separate the two, given that through the symbols they believed they did live on in some literal way.

But it’s not fair, is it? It’s not fair that the wealthy and powerful can create more or greater immortality for themselves–even on the backs of those slaves whose hope for the afterlife rested in the hands of the powerful.

But to bring the question back to us, is symbolic immortality enough? Does a mere symbolic immortality, bereft of any belief in literal immortality–of agency, relationships, love, feeling–really provide a defense against the otherwise emotionally debilitating knowledge of our imminent demise?

I agree with Jewish scholar Neil Gilman, who answers the question, “Is memory enough?” in The Death of Death this way:

…I tend to minimize the popular notion that one’s immortality rests in the memories one leaves behind, in the impact of one’s life on friends, family and community, in children and grandchildren, in the institutions one helped build, the students one taught of the books one published…

It is not sufficient for me, however, largely because this view does not acknowledge my concrete individuality as I experience it during my life here on earth. According to the view that my immortality is fulfilled through succeeding generations, my immortality merges with that of the countless others who share in shaping the identity of those who follow us. Judaism, on the other hand, provides me with a doctrine of the afterlife that affirms that despite the influence on me of countless others, I remain a totally distinct and individualized human being. It is precisely this individualized existence that is most precious to God and that God will preserve for eternity… (245).

The other important factor to add, here, is that if the memory of us is our best and only hope for immortality, (1) we won’t be around to enjoy or appreciate that memory, and (2) that memory will fade when the last person to remember us is also gone. We will then no longer exist.

Literal immortality, on the other hand, affirms that God’s creation of life–all life–is too good to come to an end. It also refuses to differentiate between the powerful and the not-powerful. The rich cannot purchase a longer memory than the poor can. The powerful cannot inscribe their names in history for longer than the weak can.