There is considerable confusion by Christians (and non-Christians) as to what inter-religious dialogue is and what it is not. From this misunderstanding, many people are hostile to it. When one goes through the criticisms launched against it, the ones who are hostile towards it rarely have explored how inter-religious dialogue is conducted, what its goals are, and more specifically, what inter-religious dialogue avoids. Their presentations of it are contrary to what inter-religious dialogue actually tries to achieve. Inter-religious dialogue desires to have people come to know and appreciate people of other faiths, and to better and more accurately understand what these faiths actually teach. Through this, it certainly hopes they will get along with one another better and will be able to work together for the betterment of society, but this can only be done after they have grown to know and understand each other better.

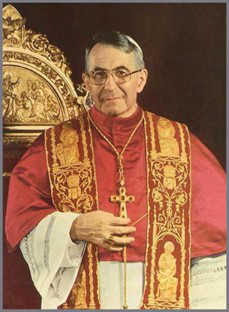

When we encounter people of a different faith, there are many things which we can and should do. One thing we should not do, however, is to fear them just because they are different from us. Much hostility in the world, much religious persecution, has come from such fear. Romans once disliked Christians because we were different from them, and they sspread all kinds of odd, false stories about Christianity which perpetuated the disdain Romans felt for Christians. Historically, this has not happened with Christians alone. Most religions have had similar stories and gossip spread about them. There is no better way to counterbalance this than by dialogue, where ignorance can be removed, and unfounded prejudices can be eliminated. Thus, inter-religious dialogue is important, because it can help provide ways for people to get to know each other better and to realize that they are not as different from one another as they might at first have thought. From dialogue, we should be able to realize that we can exist together in peace. While inter-religious dialogue should not be seen merely as a tool for peace building in the world, nonetheless, we must recognize that inter-religious dialogue helps in pursuing such a laudable and worthwhile goal. Once you know others better, it is easier to trust them and work with them for the common good. “We wish finally to express our support for all the laudable, worthy initiatives that can safeguard and increase peace in our troubled world. We call upon all good men, all who are just, honest and true of heart. We ask them to help build a dam within their nations against blind violence which can only destroy and sow seeds of ruin and sorrow. So, too, in international life, that they might bring men to mutual understanding, combing efforts that would further social progress, overcome hunger of body and ignorance of the mind, and advance those who are less endowed with the goods of this earth, yet rich in energy and desire” John Paul I, Radio Message Urbi et Orbi, Rome, 8-27-1978 in Interreligious Dialogue: The Official Teachings of the Catholic Church (1963 – 1995). ed. Francesco Gioia (Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 1997), 211.

When we encounter people of a different faith, there are many things which we can and should do. One thing we should not do, however, is to fear them just because they are different from us. Much hostility in the world, much religious persecution, has come from such fear. Romans once disliked Christians because we were different from them, and they sspread all kinds of odd, false stories about Christianity which perpetuated the disdain Romans felt for Christians. Historically, this has not happened with Christians alone. Most religions have had similar stories and gossip spread about them. There is no better way to counterbalance this than by dialogue, where ignorance can be removed, and unfounded prejudices can be eliminated. Thus, inter-religious dialogue is important, because it can help provide ways for people to get to know each other better and to realize that they are not as different from one another as they might at first have thought. From dialogue, we should be able to realize that we can exist together in peace. While inter-religious dialogue should not be seen merely as a tool for peace building in the world, nonetheless, we must recognize that inter-religious dialogue helps in pursuing such a laudable and worthwhile goal. Once you know others better, it is easier to trust them and work with them for the common good. “We wish finally to express our support for all the laudable, worthy initiatives that can safeguard and increase peace in our troubled world. We call upon all good men, all who are just, honest and true of heart. We ask them to help build a dam within their nations against blind violence which can only destroy and sow seeds of ruin and sorrow. So, too, in international life, that they might bring men to mutual understanding, combing efforts that would further social progress, overcome hunger of body and ignorance of the mind, and advance those who are less endowed with the goods of this earth, yet rich in energy and desire” John Paul I, Radio Message Urbi et Orbi, Rome, 8-27-1978 in Interreligious Dialogue: The Official Teachings of the Catholic Church (1963 – 1995). ed. Francesco Gioia (Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 1997), 211.

Many non-Christians are weary to engage inter-religious dialogue with Christians because they believe Christians involved in it are dishonest and want to use inter-religious dialogue as a tool for evangelization. Many Christians, on the other hand, do not want to be involved in inter-religious dialogue because they believe it means they would have to stop the proclamation of their faith. Both of these positions, however, come from a misunderstanding of the goals and limitations of inter-religious dialogue. While we have already looked at what inter-religious dialogue is, we still need to look at the limits of such dialogue, and the best way to do this is to understand what exactly inter-religious dialogue is not.

Probably two of the greatest mistaken beliefs many have about inter-religious dialogue are to believe that it either promotes indifferentism or that its goal is to unite all religious traditions into one supra-religious entity. Both of these, however, are far from the truth. While dialogue promotes respect of the various religious traditions of the world, this respect does not mean one has to think all religions are equal. Indeed, in inter-religious dialogue you want to meet people who are faithful to their religious tradition, and this fidelity, of course, would not be had if they did not have reasons as to why they believe and follow their own religious traditions instead of any other. “This does not mean that in entering into dialogue the partners should lay aside their respective religious convictions. The opposite is true: the sincerity of interreligious dialogue requires that each enters into it with the integrity of his or her own faith.” Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue and the Congregation for Evangelization of Peoples, Dialogue and Proclamation (Vatican: 5-19-1991), par. 48. Through dialogue, people learn to respect and understand each other. This does not mean they come to some universal agreement. If this is to be seen as a mark of indifferentism, then it would also be indifferentism for people within a religious tradition to respect each other when they hold different beliefs. For example, Augustinians, Thomists, Bonaventurians, and Scotists disagree on many theological points, yet, in spite of those differences, they can and do respect each other. No one views this to mean they are relativists. This is exactly the kind of respect one is expected to have for people who hold to different religious faiths. One appreciates them, but one also learns about them to sees what differentiates these faiths from one’s own religion. By understanding and respecting the differences, syncretism is avoided; it is only when differences are not appreciated that syncretism can emerge. Moreover, it also shows why those engaged in inter-religious dialogue must not be seen as repudiating their own religious faith. Clearly, they can only engage inter-religious dialogue as a representative (official or unofficial) of one religious belief if they actually believe it. You don’t partake of inter-religious dialogue “in the role of a believer.” If you do, you would not only be misrepresenting yourself, but, because you do not believe the religion in question, you would more likely than not misrepresent it during the dialogue. This would be quite unfair to all involved in the discussion.

Similarly, inter-religious dialogue must never be called ecumenism. Sadly many people do so, and it is because they do no know what ecumenism actually is, nor do they really know what inter-religious dialogue is about. First and foremost, ecumenism is intra-religious; for Christians, it only happens with other Christians; its goal is to find a way to achieve Christian unity, fulfilling the desire that Jesus showed in his prayer to the Father before his death. “Ecumenism is directed precisely to making the partial communion existing between Christians grow towards full communion in truth and charity” John Paul II, Ut Unum Sint (Vatican: 5-25-1995), par. 14. Some might think that the term could be used for inter-religious dialogues in an analogous sense. But this, too, is not right, because, as has been said, inter-religious dialogue does not seek to eliminate the barriers between religions. It seeks, instead, to eliminate the confusion and misunderstanding that people have about the different religious faiths, allowing them to peacefully interact with each other. Those involved in it see, as much as anyone else, the kinds of problems which would occur if people tried to unite the religions of the world together as one supra-religious entity: it would create a religious mess and would satisfy no one.

Just as inter-religious dialogue should not lead to syncretism, it also should not lead to proselytism. In the dialogue, one does not go in seeking to convert the other, but to know them, to understand them. Because of this, inter-religious dialogue is not to be seen as debate; one does not go in with the desire to prove all other religions are wrong and yours alone is right. This does not mean one is not to offer difficult questions: when you learn about a religious belief or tradition which is confusing to you, you ask about it, even if it is clearly a difficult issue to address. Tough questions are welcome as long as they are aimed for better appreciation and understanding of the other faith; indeed, such questions when asked of us can help us affirm our own faith, because they might lead us to delve deeper into our faith on issues we have not done before. Clearly, however, the questions must not have any underpinning of superiority to them: that is, they must not be asked to show why “my religion has better answers to this question than yours.” While one might believe it, how will they really know this to be so, if they do not know how the other religion would answer the question? And if you think you know the answer before it is given, do you really want an answer?

Just as inter-religious dialogue should not lead to syncretism, it also should not lead to proselytism. In the dialogue, one does not go in seeking to convert the other, but to know them, to understand them. Because of this, inter-religious dialogue is not to be seen as debate; one does not go in with the desire to prove all other religions are wrong and yours alone is right. This does not mean one is not to offer difficult questions: when you learn about a religious belief or tradition which is confusing to you, you ask about it, even if it is clearly a difficult issue to address. Tough questions are welcome as long as they are aimed for better appreciation and understanding of the other faith; indeed, such questions when asked of us can help us affirm our own faith, because they might lead us to delve deeper into our faith on issues we have not done before. Clearly, however, the questions must not have any underpinning of superiority to them: that is, they must not be asked to show why “my religion has better answers to this question than yours.” While one might believe it, how will they really know this to be so, if they do not know how the other religion would answer the question? And if you think you know the answer before it is given, do you really want an answer?

It must also be said that interest in inter-religious dialogue and its proper, respectful engagement, does not mean one should not at other times be interested in propagating one’s faith. The two issues are different. Because most of us live in a pluralistic society where we interact with members of different religious faiths on a daily basis, most of us should be involved in such dialogue at some level. Yet this does not mean we will then lose sight of our own faith; if we believe it to be the truth, and if we believe its teachings would be beneficial to others, then we should also be interested in proclaiming it to them. Of course, this should not happen in the middle of inter-religious dialogue. At other times, at other places, if we do so respectfully to those around us, we can and should work for the propagation of our faith. How this is to be done is beyond the scope of our current discussion, but, clearly, there are good and bad ways to propagate one’s faith. Yet, the ability to proclaim one’s religious beliefs is a right which must be held to and affirmed by every nation. Some people might think that interest in inter-religious dialogue and a desire to propagate one’s faith can not go together. If you want to proclaim your religious faith, can you really be open to the other? However, this is not so. Indeed, “Interreligious dialogue […] is promoted, not hindered, when there is free proclamation” Francis Cardinal Arinze, Meeting Other Believers (Huntington, Indiana: OurSundayVistor, 1997). One who proclaims their faith to others, if they want to be heard and listened to, will do so with sensitivity and understanding, that is, they will appreciate where others are coming from, and will work to build up those truths the others possess as a part of their evangelization. How can they do this if they do not know what others believe? Moreover, the one who wants to proclaim their faith takes that faith seriously; they would be the kind of person to talk to if one wants to learn what their faith teaches. This means they would be a great participant in inter-religious dialogues as long as they understand the limits of the dialogue and understand it is not a place where the participants try to convert one another.

Possibly another great mistake people have about inter-religious dialogue is that they think it must be a dialogue on philosophical or doctrinal issues. While certainly these are important, inter-religious dialogue must not be seen merely as a symposium of philosophers or theologians. There is far more to a religion than this. “Religions are much more than doctrines. Within one religion there may even be a pluralism of doctrines. To pin down a religion to a certain definite doctrinal set is to kill the religion” Raimon Panikkar, The Intra-Religious Dialogue (New York: Paulist Press, 1999), 65. We can find many other ways to approach and appreciate religions than by having a dialogue exclusively on their doctrinal beliefs. A religion is more than a selection of ideas but a lived experience; it manifests itself in many ways. Thus, for a religion, its rituals, stories, histories, myths, and holiness codes are just as important, and sometimes more important, than its doctrinal content. There are many ways believers can appreciate these; religious experts will understand them differently from the ordinary believer. Therefore, while religious experts certainly are important in inter-religious dialogue, it is clear that inter-religious dialogue is not a dialogue solely for such “experts.” Rather, it is open to anyone who believes and can share their beliefs with others, and who are interested, in return to learn about the beliefs of others.

Likewise, we must not think inter-religious dialogue is about the study of religion or for engaging in comparative religion. The problem here is that the discipline of religious studies tends to objectify religion and comparative religion takes these objectifications further, and uses objectified categories as a hermeneutical tool which then reads all religious traditions through a secondary lens. While religious studies and comparative religions are useful scholarly pursuits, they can hinder the goals of inter-religious dialogue because in such dialogue the point is to give the primacy of interpretation to members of the religious faiths being represented in the dialogue. A scholarly overlay used to read into the results of the dialogue would work against this. One would no longer be listening to the other; instead you would already be assuming what the other believes. But, this is not to say, in the dialogue, there will be no comparative work going on. When it is done, it must be free-flowing, and based upon what it is said, and not a-priori categorization.

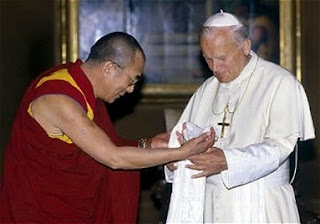

Finally, something must be said about peace building. Clearly, dialogue can help us realize that most people desire peace. “From the acceptance of the fact of religiously pluralistic societies, the followers of the various religions have to learn to work together to promote peace. Peace has no religious frontiers. There is no separate Christian peace, Muslim peace, Hindu peace, or Buddhist peace. Religions have no choice but to work together to promote peace” Francis Cardinal Arinze, Religions For Peace (New York: Doubleday, 2002), 57. Moreover, through the practice of inter-religious dialogue, many factors which hinder peace can be overcome. “To build peace and maintain it, the cooperation of all is required. Believers in the various religions have to be helped to overcome misunderstandings, stereotypes, caricatures, and other prejudices, inherited or acquired” ibid., 57.However, while this is true, we must not think inter-religious dialogue is solely a tool for peace building. To do so is to abuse the dialogue. First and foremost it is to be used as way of getting people to better understand and appreciate each other and their religious traditions. If this is ignored, and people dialogue with members of other religions, trying to create peace without trying to get to know the people they want peace with, the peace will be without a proper foundation and will fall like a house of cards. You just do not dialogue with others, treating them as tools for an end. You must first realize they are subjects in their own right and it is through this that true peace building flows as slowly begin to do more than know them and how they think, but trust them as well.

To summarize, inter-religious dialogue is not:

1) Religious indifference

2) Syncretism

3) Ecumenism

4) A repudiation of one’s own faith

5) Proselytism

6) Replacement for proclamation

7) Debate

8) Merely a symposium of philosophical ideas or theological doctrines

9) Merely for experts

10) Merely a study of religion or comparative religion

11) Merely a tool for peace building