Recently, a new translation of the Bible has been published, and it is one that people might want to consider obtaining for themselves: The Orthodox Study Bible. Yes, one might own a previous edition, but it was only the New Testament and the Psalms and it contained only a few study notes to help the reader. Now, the Bible is complete, and it provides an important contribution to the English speaking world by offering a new, modern translation of the Septuagint for the Old Testament.

Recently, a new translation of the Bible has been published, and it is one that people might want to consider obtaining for themselves: The Orthodox Study Bible. Yes, one might own a previous edition, but it was only the New Testament and the Psalms and it contained only a few study notes to help the reader. Now, the Bible is complete, and it provides an important contribution to the English speaking world by offering a new, modern translation of the Septuagint for the Old Testament.

The East views the Septuagint as an inspired translation of the Tanakh, as superior to the later Masoretic Text, and as the text which is to be used for the Old Testament. Of course it is known that the New Testament writers used it (not exclusively, to be sure; there are some quotes which reflect the proto-Masoretic tradition). But what people who are unfamiliar with the Septuagint do not know is that the texts of several books of the Tanakh differ in the Septuagint from the later Masoretic texts; sometimes it is only minor differences, sometimes it is major. One of my favorite examples of this comes from the end of Job:

So Job died, old and full of days. It is written that he will rise with those whom the Lord resurrects.

This man is described in the Syriac book as living in the land of Ausitis, on the boarders of Edom and Arabia. Previously his name was Jobab. He took an Arabian wife and begot a son named Ennon. But he himself was the son of his father, Zare, one of the sons of Esau, and of his mother, Bosorra. Thus he was the fifth son from Abraham.

Now these were the kings who reigned in Edom, over which country he also ruled. First, there was Balak the son of Beor, and the name of his city was Dennaba. But after Balak, there was Jobab, who is called Job. After him, there was Asom, who was the ruler out of the country of Teman. After him, there was Adad the son of Barad, who destroyed Midian in the plain of Moab; and the name of his city was Gethaim. Now his friends who came to him were: Eliphaz, of the children of Esau, kind of the Temanites; Bildad, ruler of the Shuhites; and Zophar, king of the Minians. (Job 42:17-22; SAAS).

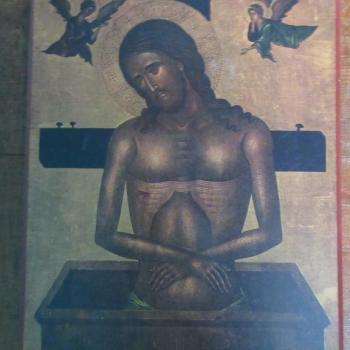

As can be seen, the Septuagint provides information as to who Job was and where it was he lived and reigned. More importantly, the text makes a clear declaration of the resurrection of the dead (explaining why this passage is read on Holy Friday in the East). There are many additions like this to the books of the Old Testament throughout the Septuagint, although, it must be noted, some aspects of the Masoretic Text do not find themselves in the Septuagint (sometimes, whole chapters are missing). Which version is the most accurate? That’s up to debate, since we have proto-Masoretic and proto-Septuagint versions of the Tanakh in Hebrew, attesting to the fact that there were multiple Biblical traditions even in pre-Christian times. Both, then, should be considered important, and both should be examined when studying the Scripture. And it is for this reason alone that one interested in Biblical study should have a copy of the Septuagint, either in the Greek, or in English, especially because the Greek text often clarifies ambiguities found in the Hebrew.

The rest of The Orthodox Study Bible is a fine example of what a “Study Bible” should be like. It provides significant notes throughout, based in part on patristic understanding of Scripture, and emphasizing Orthodox dogmatics (Christology, the Trinity, Soteriology, et. al). I think they are at their best when they trace the way the Old Testament prefigures the New, while, for the most part, they are at their worst when they ignore contemporary Biblical research and the gains made in modern exegetics. But that’s not the point of this edition of the Bible, and so, it is only a minor issue. All in all, it’s not the notes which make me suggest this edition of the Bible, but the text of the Old Testament.

[UPDATE]: For some reason, I didn’t read one of the early pages of the OSB, and when I did, I found something slightly disappointing. While the text of the OT is indeed following the LXX, the translators often had the Brenton and the NKJV OT to the side as tools to help in their translation. And when they felt there was little to no difference between the NKJV with the LXX, they went with the NKJV translation. It’s a minor quibble; they still work with the LXX and add what is in the LXX into the OSB, however, it makes the translation slightly less than what I originally thought it was meant to be. Since I did not possess a NKJV already, I did not notice this fact; if I did, I probably would have noticed the way the OSB borrows from the NKJV OT.