While the interviewer in this clip can be a little annoying, he also has a point. Speaker Pelosi says everyone who works should be paid the minimum wage, yet many of the people who work for her don’t make the minimum wage. The fact that we choose to label one “employment” and the other “an internship” would not seem to make much difference from a moral point of view. If it did, then as the interviewer rightly notes, businesses could simply evade minimum wage laws by classifying their employees as interns. On the face of it, then, Speaker Pelosi’s stance here would seem to just be another example of a trend I’ve noted previously, namely that many advocates of the minimum wage think an exception ought to be made in their own case.

My guess, however, is that most advocates of a legal minimum wage would also say an exception should be made for interns, even though most of them do not themselves utilize intern labor. This could just be a result of confusion, but the fact that so many share this intuition suggests that it is at least possible there is something else going on.

One might try to defend unpaid or low paying internships, by noting that interns learn valuable skills and gain important job experience which, while not reflected in their pay checks, could be of enormous value to them. But while this is no doubt true, the same could be said of many low paying, entry level positions.

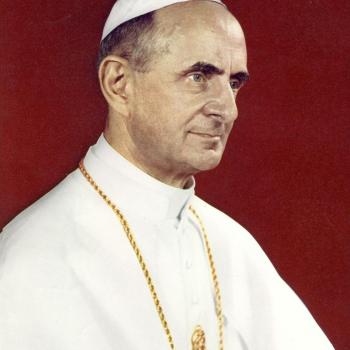

I think the main reason people do not object to internships is because of the type of person they expect to be filling the positions. As Pope Leo XIII noted when setting out the Church’s teaching on the Just Wage, labor often contains both a personal and a necessary dimension:

were we to consider labor merely in so far as it is personal, doubtless it would be within the workman’s right to accept any rate of wages whatsoever; for in the same way as he is free to work or not, so is he free to accept a small wage or even none at all. But our conclusion must be very different if, together with the personal element in a man’s work, we consider the fact that work is also necessary for him to live: these two aspects of his work are separable in thought, but not in reality. The preservation of life is the bounden duty of one and all, and to be wanting therein is a crime. It necessarily follows that each one has a natural right to procure what is required in order to live, and the poor can procure that in no other way than by what they can earn through their work.

But while work often contains both a personal and a necessary dimension, this is not always the case. A person has some means of support other than his work. So a student or youth may be supported by their family, or someone may have accumulated enough savings that their basic needs will be met even if they work for no pay. In such a case, the necessary dimension of work disappears, and we are left only with Pope Leo’s admission that “to consider labor merely in so far as it is personal, doubtless it would be within the workman’s right to accept any rate of wages whatsoever; for in the same way as he is free to work or not, so is he free to accept a small wage or even none at all.”

Of course, once we admit this, the case for a minimum wage law becomes much more tenuous. But that is a subject perhaps best left for another time.