Let’s repeat, once again, what the current healthcare reform proposal is actually trying to do. Despite all the (deliberate) obfuscation, it’s really quite simple. Paul Krugman says it best:

“The essence is really quite simple: regulation of insurers, so that they can’t cherry-pick only the healthy, and subsidies, so that all Americans can afford insurance. Everything else is about making that core work. Individual mandates are a way to prevent gaming of the system by people who don’t sign up until they’re sick; employer mandates a way to hold down the on-budget costs by preventing a rush by employers to drop insurance; the public option a way to create effective competition and hold costs down further. But what it means for the individual will be that insurers can’t reject you, and if your income is relatively low, the government will help pay your premiums. That’s it. Any commentator who whines that he just doesn’t understand it is basically saying that he doesn’t want to understand it.”

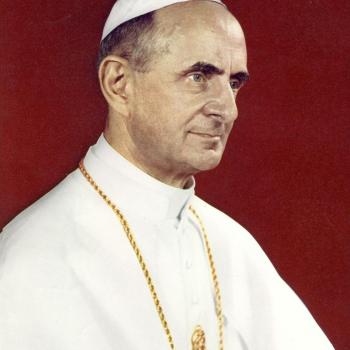

Not so hard to understand, is it? But of course, much of the right-wing opposition is ideological. They can sniff that the government is trying to “interfere” with the private sector, to stop it doing various things. (I will let pass the irony of the people who are actually under a single-payer system- the elderly- being the most opposed to “big government” heathcare). This purely ideological opposition sounds like a throwback to the laissez-faire liberalism condemned by all popes from Leo XIII onwards, which viewed the free exchange between market participants as a tent of natural justice. But we know that the private market does not embody virtue. It is merely a means to an end, that of supporting the common good. If there is an egregious violation of the common good, as there is in the current health insurance system, then it is incumbent on the government to step in and fix the problem. This has been at the core of Catholic social teaching for over a century. But it seems to be lost in the current debate.

Here is the renowned economist, Jimmy Akin, weighing in on the problem:

“Any reasoned look at what is being proposed will lead to the conclusion that the long term effects of the program will be to increase costs (something bureaucracy does exceedingly well), increase taxes, lead to greater deficits, lead to health care rationing, drive private insurance out of the market, promote euthanasia, lead to more nanny state interventions in people’s lives, promote greater dependency on government, stifle the development of new medical treatments (just when we’re getting to the point that we might start seriously extending the human life), and basically kill a lot of people, both here in the U.S. and in other countries, which have been relying on American innovation since their own socialized medical systems put the squeeze on domestic innovation.”

Where does Akin get this stuff? It is clear that he simply dislikes government on ideological grounds, because none of his arguments make the slightest bit of sense. After all, governments are supposed to be inefficient, so they will be inefficient. Why then do single-payer systems manage to deliver comparable quality healthcare without leaving anyone behind, and do so at about half the cost of the US system? You can argue against single-payer systems on any number of grounds, but cost is certainly not one of them. And anyway, why is it that private insurance costs are increasing dramatically faster than public insurance costs? Why does Akin worry about paying for healthcare subsidies to the poor by increasing taxes on rich, as opposed to the current system of the poor being left behind and the middle class bearing the brunt of the cost in lower wages?

Rationing, he says. Does he not understand that the private insurance market is rather adept at rationing? Can he think of a single healthcare plan where the beneficiary can have all the healthcare they like covered under the plan? Oh yes, the current system does rationing very well. 47 million are rationed out completely. A further 25 million are underinsured, meaning they have to forsake healthcare based on cost. Rationing. And when insurance companies refuse coverage, dropping coverage, and denying claims — as they do in thecurrent system and which disproportionately affects the poor – then yes, that too is rationing. So what then is he talking about? Perhaps the misconception that single-payer systems ration extensively on quantity rather than cost? This is simply not true, but is beside the point, because the current proposals are nowhere close to single payer. I will merely point out that the best systems, the ones that mix public and private coverage, generally do very well on speedy access to healthcare – and without leaving anybody behind. Oh yes, and they probably kill a lot fewer people than the US system, as they grant universal healthcare and emphasize primarty care. In fact, the US scores pretty badly on life expectancy and mortality indices.

Of course, he brings up the euthanasia canard. Why? Because Sarah Palin made it up? In fact, I think it is far more likely that a life would be ended in a private system where cost is the bottom line, especially if the family cannot afford the princely sums that would be needed. In fact, the law quite frequently allows hospitals and healthcare providers to withdraw care from patients they deem too expensive to continue sustaining. And remember the example of Elizabeth Anscombe’s daughter, a stroke victim whose life was saved by the “socialist” British healthcare system after the American system would have pulled the plug.

Let’s get to the bottom line. If one accepts healthcare as a basic human right, as the Catholic Church does, then one has to accept that the current system is deeply immoral. One has to accept that any reform must begin by regulating the behavior of private insurers, whatever you think of a public option (and remember, the whole point of the public option is simply to control costs — once again, as with a market solution, a mere means to an end). What does this reform do? It puts in place a code of conduct for insurance companies, and allows those without insurance to access it through a health exchange, with the help of subsidies. In other words, it tries to level the playing field a little, to increase the bargaining power of the ordinary person. Remember the insight of Leo XIII– there was a law of natural justice greater than the law of the market, and the worker could be “the victim of force and injustice” if this was not respected. This is the reason behind the Church’s staunch support of unions — to make an unequal bargaining relationship more equal, to allow the outcome better accord with natural justice. I would contend the same is true in healthcare — just as unions bring workers together to protect them from exploitation, so do health exchanges and regulation of insurance companies give the uninsured greater leverage, making it more likely that natural justice (in this case, the right to healthcare) wins out over the market solution.

None of this makes any sense if you believe in the Reaganite mantra that government can only bring ill. But it makes perfect sense if you read it through the prism of Catholic social teaching.