The Trinity Zizek Collective, a philosophy reading group dedicated to the works of Slavoj Zizek, has started up again. This has got me thinking about his work, and so this is the first of what I suspect will be several posts related to Zizek’s ideas. Let me begin with a disclaimer: though I have been reading Zizek for several years, I do not claim to be an expert: his writing is dense, convoluted and occasionally contradictory. Corrections to my reading are welcome.

At the heart of Zizek’s political philosophy is his use of Lacanian psychoanalysis to explore social questions, in particular the role of ideology in upholding the existing social order. He argues (cogently if not persuasively) that ideology functions not only at a rational level, but at a deeper, unconscious level. An ideology is accepted because it satisfies deep seated psychological needs in the believer. To Lacan, the human psyche is built around two dimensions. (Actually, there are more than two, but here I want to concentrate on just two.) First, there is a recognition of a lack or gap in our identity: there is something about us that we sense but cannot name. We literally cannot put it into words, because there is no linguistic construction (symbolic order in Lacanian terms) that fully captures who we are. However, given that we are verbal creatures, we constantly try to cover over this gap. We are always looking for some symbolic construction that explains fully who we are. From a Christian perspective, I see this as secular echo of Augustine’s famous aphorism that our hearts are restless until they rest in God.

Second, the human psyche is shaped by desire. But beyond the fundamental physical urges—to eat, to sleep, to be warm, etc.—our desires are shaped by our social interactions. What we desire is what others tell us is desirable. And on a basic level, this gets transmuted into desiring that the other (parents, friends, society in general) desires us. In other words, the root of our desires is that we want other people to like us, respect us, love us, and we believe that we can gain this by having, doing or being something that they want. Much of modern advertising seems built on this premise: I am told to buy a fast car, not because I need to drive fast when I commute to work, but because by doing so I will make myself desirable in some way to others.

To Zizek, these two dimensions explain how an ideology is successful. An ideology will be held, even in the face of rational evidence to the contrary, if it provides its believers with a comprehensive explanation of who they are and what they have to do to win the approval of “the other.” Zizek’s classic example is Nazism, but his argument is that this underlies every ideological system, including Christianity. (To avoid a strawman argument: he is not, thereby, equating all ideological systems with Nazism.) Therefore, to understand an ideology, we must not look only at the rational superstructure, but at its unconscious component, at its role in the “libidinal economy.”

The purpose of this analysis is to help us see the constraints we are operating under and to help us expand our understanding of what is possible. Zizek argues that our goal, as individuals and as a society, is to overcome ideology: to find ground on which to stand to criticize it, to point out both its failure to explain who we really are and how it gets us to act against our own interests (in favor of the interests of the dominant power structure) by convincing us that we will be loved/respected/wanted if we do these things. In Lacanian terms, our goal is to traverse the fantasy.

This is straightforward in the abstract, or when considering an ideological structure that we do not believe in. It is easy to “analyze” Germans in the 1930’s and see how they were led astray by Nazism. The real challenge is to traverse the fantasy and critique an ideological system in which we are embedded. Indeed, one can be so immersed in an ideological system that one cannot perceive that it even exists. Zizek’s favorite example of this is Fukuyama’s book “The End of History”, in which Fukuyama argued that with the demise of communism we had entered a post-ideological era: global capitalism and liberal democracy were not ideologies but instead just the way things were meant to be. When overcoming an ideology, it is not enough to criticize its rational component. One can take a stance of cynical distance to capitalism and liberal democracy (or Soviet era communism) and still be thoroughly enmeshed in it, still seeking the unconscious satisfaction that it provides. One must therefore expose the roots of the gratification it provides.

The purpose of this prolegomena is that I want to view Christianity through this critical lens. One could argue naively that Christianity is just another ideological system that holds us in thrall, and that we need to traverse this fantasy (here using fantasy in both its technical and pejorative sense) and move beyond these superstitious beliefs. While this argument might be attractive to the new athiests (Hitchens, Dawkins, et al.) Zizek does not make this argument, even though he is an atheist. Rather, he criticizes Christianity for betraying itself, for rejecting the radical message that it superficially proclaims. He concludes his book The Puppet and The Dwarf: The Perverse Core of Christianity by writing:

“In what is perhaps the highest example of Hegelian Aufhebung, it is possible today to redeem this core of Christianity only in the gesture of abandoning the shell of institutional organization (and, even more so, its explicit religious experience). The gap here is irreducible: either one drops the religious form, or one maintains the form but loses the essence. That is the ultimate heroic gesture that awaits Christianity: in order to save its treasure, it has to sacrifice itself—like Christ, who had to die so that Christianity could emerge.” (p. 171)

I am not going to try to recount the entire argument Zizek makes to support this conclusion—in the end it rests on his materialist prejudices and a flawed reading of the Passion narratives. Nevertheless, in reading this book it seemed to me that Zizek had hit upon a trenchant critique of Christianity, one which we would do well to take seriously. If we look at the “ordinary” practice of Catholicism (or Christianity in general), we see that we are often caught up in externalities—the forms of being Catholic—and that the substance seems to be overlooked. Indeed, the radical core of the Christian message is often actively discounted: “Yes, scripture says X and the saints did Y, but what is really important for us is Z.” Far too often Christianity is functioning not as a liberation from the world, but as an ideological system that keeps Catholics chained to the world—in Zizekian terms, true faith is replaced by a Christian fantasy.

The external forms that masquerade as “true Catholicism” depend on whether one is “liberal” or “conservative” (suggesting that there are at least two ideological fantasies in play in the Church today): devotion to “traditional Catholicism” or “the spirit of Vatican II”, rubricism, inclusiveness, pro-life activism, social justice work, etc. A commonality emerges if we examine them from a Zizekian perspective. The psychological attractiveness lies in the reassurance that if I believe/do/act in these ways, then I will be a “real” Catholic (in the sense of a totalizing identity) and, perhaps even more importantly, the other—the Pope, the institutional Church, my pastor, the other members of my parish, the beloved community—will love me and accept me.

This interpretation, however, does not fully explain the power of these ideologies, since it ignores the transcendent dimension of the rational superstructure: it does not include God. The adherents of one of these Christian fantasies will claim that they believe and act as they do because it is in conformity with God’s will. In other words, the ultimate libidinal reward of all of these fantasies is this: if I do/believe/act in these ways, then God will love me, and this love will be manifested in my acceptance by the Pope, the beloved community, etc. God, in this fantasy, has been reduced to the “Big Other”: a symbolic construct of who we (unconsciously) think God is or ought to be: a powerful ruler, the distant, all knowing parent, someone whose approval we crave and whose love we must earn.

This fantasy (or more precisely, an older Jewish version of this fantasy) is clearly visible in the New Testament, beginning with the preaching of John the Baptist:

But when [John] saw many of the Pharisees and Sadducees coming to where he was baptizing, he said to them: “You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the coming wrath? Produce fruit in keeping with repentance. And do not think you can say to yourselves, ‘We have Abraham as our father.’ I tell you that out of these stones God can raise up children for Abraham. (Luke 3:7-9)

The Pharisees saw their religious identity in terms of their descent from Abraham and adherence to the Law. They would remain in the family, as it were, pleasing their Father (and thereby pleasing God) if they kept to the external forms of the law and the customs surrounding them. John, and Jesus after him, challenges them to look beyond this (shallow) understanding of God.

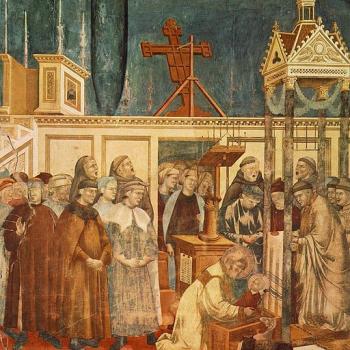

I also think that this approach provides a useful perspective for understanding medieval Europe. Viewed nostalgically it was the age of Christendom, when Catholic teaching permeated and shaped culture and society. But at the same time, it was also a period of very weak faith. Consider just the example of St. Francis of Assisi, whose biographers commend him for reawakening the faith in the hearts of many in whom it had grown cold. One the one hand, they had no faith (as a saint such as Francis would understand it), yet they lived in the “age of Faith” and hewed willingly to their Catholic identity. Why? Because it provided the psychological reassurance of belonging, the illusion that by doing so they were securing God’s love and salvation. Much of the “economy” of salvation—the indulgences, the bequests to the poor, the endless masses—becomes more understandable when we see it in these terms.

Continuing a Zizekian analysis, we must consider what it would mean to traverse the Christian fantasy. Zizek, as an atheist, would answer that it means accepting that there is no “big Other”, no God, who loves us and knows all the answers. As Christians, however, we reject this: faith tells us that there is a God. Faith also tells that we cannot really understand God through our own reasoning: we can only truly understand God as He reveals Himself to us. The heart of this revelation is that there is a God who loves us, and this love is both unconditional and prior to anything we do or believe. The radical core of Christian faith is that we believe that we cannot earn God’s love, that God’s love does not increase or decrease depending on our actions or beliefs. I heard this best expressed on a live album by the Christian rock band Petra. In the middle of the performance they had an altar call (a little weird to hear on an album) in which the lead singer cries out, “God loves you with an everlasting love; he always has and always will, whether you decide to serve him or not.”

This language is echoed throughout the New Testament. Rather than the old covenant with its contractual aspect of mutual obligations (“You will be my people and I will be your God”) we have a new covenant in love. And the first letter of John makes clear: “Love consists in this: not that we loved God, but that He loved us…” (1 John 4:10). In his farewell discourse, Jesus gives his disciples a new commandment: “love one another as I have loved you” (John 13:34). Jesus is making it clear that God’s love is not contingent on this commandment: “I have loved you” places God’s love first and attaches no strings. Rather, our love for one another should be a consequence of accepting that God loves us.

If this is the heart of Christian faith, then why (in this reading) do so few people accept it fully? Perhaps because it is hard to let go, to admit that we cannot know ourselves totally and make ourselves worthy of being loved by God. We cannot move past our need to be wanted, respected, loved by the “other”, in whatever form it takes in our lives. We are told to model ourselves on the saints, but are terrified by them: they live in the world but are not of it, and they do not care what the world (their friends, their neighbors and often the institutional Church) thinks of them. And because of this they are marginalized or killed, rejected by the society we want to accept us. Unless we abandon our desire to be desired, our saints are safe only if they are kept at a distance: remembered on their feast days but otherwise ignored. Think of Dorothy Day’s acerbic comment: “Don’t make me a saint: I don’t want to be dismissed so easily!”

The importance of this Zizekian reading is that it reinforces for us the commandment of Jesus: “love one another as I have loved you.” To be a Christian is to love unconditionally. If we are going to traverse the Christian fantasy (and I definitely include myself in this), then we must stop seeking the acceptance of others and stop trying to earn God’s love. Instead, we have to help one another accept that we are already loved by God by modeling this love. This is not an easy thing to do, but today, on the feast of Corpus Christi, we are strengthened by same God who loves us: “remember that I am with you until the very end of the age” (Mt 28:20).