When it comes to certainty, I have a scattered heart and mind. I won’t say that I am uncertain about certainty, cause that’s cliché and precisely one of the things I am uncertain about. I am quite certain about this and other uncertainties I have. Unlike Kyle, I don’t have a rating for certainty, religious or otherwise. (Is there a kind of certainty that is not religious?)

When it comes to certainty, I have a scattered heart and mind. I won’t say that I am uncertain about certainty, cause that’s cliché and precisely one of the things I am uncertain about. I am quite certain about this and other uncertainties I have. Unlike Kyle, I don’t have a rating for certainty, religious or otherwise. (Is there a kind of certainty that is not religious?)

For starters, I constantly run into the same issue: I don’t know what people mean by the term ‘certainty.’ When people use the word ‘certainty,’ it’s usually loaded. The sides taken are usually predictable, as are the reactions that follow.

Philosophically speaking, the term ‘certainty’ is a hint that tells what brand of philosopher one is. In religious circles, the same hints often apply. When a dose of politics is added, things can get nasty and confusing. Another pissing match. By the end of it all, I usually end up convinced (certain, even!) that everyone is using the term ‘certainty’ in different ways, uncertain as to what they are trying to say exactly.

This is unfortunate. Unlike thornier terms, I think that ‘certainty’ can be described and understood in a way that shows something fairly universal—and important—to human experience. The term ‘certainty,’ in ordinary language, attempts to show what happens when someone is convinced of something all the way down: down to the bones, to the marrow. To the root.

This sense of the term ‘certainty’ differs from other versions that dwell on the logical rigors of certainty. For the positivist and the scientist, certainty is about the head, not the heart. For me it’s both, with an emphasis on the heart. I am absolutely certain that one does not become certain without the uncertainties of sentiment, emotion, the heart. As William James put it in The Will to Believe, “If your heart does not want a world of moral reality, your head will assuredly never make you believe in one.”

It is this emotional fact of certainty that makes it so difficult to deal with: when people argue for or against certainty they are convinced in ways that go beyond rational argument and logical reasoning, their meanings are held close to the chest, each with her own privately felt beliefs. In his Confessions, Augustine shows us the simultaneous juxtaposition of certainty and doubt in a majestic, moving way.

For what it’s worth, here is the way I feel about certainty:

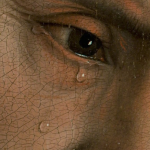

For me, certainty means the things I believe, even when I don’t understand them, but especially when I think that I do. Certainty is the absolute feeling I get in my gut and my bones, the literal heartache that seers and sizzles just beneath my ribs, the absolute beauty of a moment, a thought, or a thing—a blue note. I am certain when I am in love, when I desire something, especially when I miss someone. When I mourn. The heart of certainty is the inexhaustible desire for love, for God. The merciless, constant, driving rhythm that keeps me alive. Of this I am absolutely, totally certain.

Yet this certainty makes me profoundly uncertain. It fills me with doubt, questions, insecurities. Despair. It also often make me extremely happy. As Stevie Wonder put it: Overjoyed.

Because of my certainty, because I sense and feel myself 100% alive, yearning for touch and for love, because of all of this and more: I am uncertain about what it means, where it comes from, who I am, whether it is real or not, what will come of it all. And philosophy only makes things worse.

I also know that the things that I am most certain about are the very places where my deepest, unconscious doubts lurk. The certainty of love conceals the dark possibility that perhaps I am alone, unloved, hated. Abandoned to my own self loathing. When I emphasize this or that “certainty,” I conceal the insecurities that assault it when my head hits the pillow. If I can rest easy, then, perhaps my certainty is too cheap and easy. The psychic secret of certainty is uncertainty. Anything worth believing-in comes infected with doubt.

It is important to be certain and uncertain, to be in and out of love; to feel the warm, safe embrace of being secure and the empty, shameful alienation of being insecure. When we are naked, this is a time when we can experience intimacy and abuse. The vulnerable, naked body can be a lover or a lynching victim—or both.

Certainty and uncertainty are like nakedness. They find their way into my greatest conviction, my most cherished belief that conceals my deepest fear and doubt: the love of God.