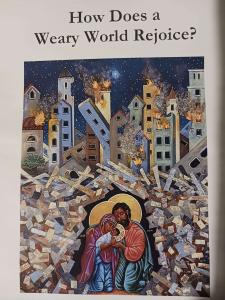

Visiting family for Christmas affords the opportunity to keep the feast among both Mennonites and Catholics, the two branches of the Christian tradition that I consider home. Even though they don’t currently live in or near any of the multiple communities in which my faith was formed, being among Mennonites invariably feels like a homecoming of sorts, a return to a native country from which I may have in some sense expatriated, but which can never not be home.

Why do Mennonites …?

By evening on Christmas Eve, a Sunday this year, I’ve been to a vigil mass and a Sunday service for the fourth Sunday of Advent, and now a Christmas Eve service at a third church. This is structured similarly to a service of lessons and carols, with sets of hymns following scripture readings accompanied by a gradually building live nativity tableau. Costumes are on the minimalist side, intentionally combining a few of the typical old-timey props with modern work clothes. I particularly like the angel Gabriel’s curled metal trumpet and neon green construction vest, as well as the very real baby portraying Jesus demonstrating (until Mary whips out a bottle) the ridiculousness of that most eyeroll-worthy line, “But little Lord Jesus, no crying he makes.”

Four-part hymns are my musical and spiritual heart language. We sing one hymn that’s new to me and appealing with a singable melody and inspiring text; most are refreshingly familiar.

Until they’re not.

The most recent Mennonite hymnal, published in 2020, has a good deal of overlap with the previous iteration more familiar to me, but with textual changes frequent enough to jolt me out of my sense of at-homeness every time I sing from it: numerous words from well-known lines and even scriptural references have been interrogated under the harsh light of postmodern sensitivities and excised.

The newborn king, at least, is still there, but “God the king” is out. And just as I think we’re going to get through “Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming” without a jolt, there it is in what was, “Dispel in glorious splendor / the darkness everywhere”: “the darkness” has become “gloom and grief”.

Is it being read in a racialized sense? I try to follow the reasoning: I’ve heard the questions raised about the symbology of color, and I’ve said that I want to extricate what traces of racism are in me, and myself from complicity in its structures, and I know it can be subtle. But the image of light dispelling darkness is so deeply biblical that I just want to plead, “It’s not about people!” Indeed, what it makes me think of is the passage from Isaiah that I’ll hear later at midnight mass:

“The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light;

upon those who dwelt in the land of gloom, a light has shone.”

Or the prologue to the Gospel of John:

“The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.”

A redeeming moment is a solo performance of “O Holy Night” with just the right degree of musical expressiveness, just enough melodic variations to add some variety and textual emphasis, and best of all, the oft-butchered rhyme scheme kept perfectly intact for all three verses. After this, we circle the sanctuary for a candlelit singing of “Silent Night” – four verses with, blessed relief, no jolting text changes – and I am once again at home.

Why do Catholics …?

I arrive at midnight mass in time to hear the choral prelude, accompanied by a very good violinist. The church is not yet full, and I slide into the middle of an empty pew a few rows from the front. A few minutes later, a solitary older man enters the same pew and sits at the very end – a popular seating choice I’ve observed in every U.S. Catholic parish I’ve been to.

Why do Catholics do that?

I’ve asked this question a time or two and gotten answers claiming serious claustrophobia, which would be more believable if it weren’t so ubiquitous. There can’t be enough clinically claustrophobic people in every parish to explain this phenomenon. I can only conclude that something in U.S. Catholic culture is driving it. Could it be related to the same sense of mass attendance as grudging obligation that draws complaints from parishioners any time a Sunday mass goes one minute past an hour? The desire to check a box and high-tail it out as quickly as possible? That’s the best guess I can make, although I can’t be sure. Whatever the reason, it requires anyone coming in after the ends of the pews fill up (and they are almost always the first seats to fill up) to inconvenience someone in order to take a seat, either by climbing over them or by making them stand up and move. It feels inhospitable.

As I’m mulling over this and other peeves of mine, ushers come through with boxes of candles, and my lone pew-mate gestures for a second one which he passes to me. I mouth a thank-you, and he flashes me a warm smile and a thumbs-up. As simple an interaction as this is, it’s enough to transform him from a mere peeve to a fellow pilgrim, as of course he’s been all along.

One of the communion hymns is, once again, “Away in a Manger”, and I find myself praying that I won’t have to take communion as the “no crying” line is sung. Verse 1 ends with plenty of people ahead of me, but when the parish musicians go into an instrumental verse, I actually start to wonder if Little Lord Jesus is pranking me. (If he is, thankfully, it misses.)

After communion, I notice the row of perhaps twenty-somethings in front of me in another common position, half kneeling on the kneeler while half sitting in the pew. Again I ponder the ubiquity of this position, its awkward noncommittal halfway-thereness. Why not just pick one? Unless someone wants to kneel but has difficulty holding the position … I remind myself that not all health conditions are visible; it’s not for me to know whether someone is taking a position out of laziness or necessity. Still, my inner critic insists, it’s done too often for everyone who does it to have a good excuse. And yet, my inner devil’s advocate counters, maybe someone is half-kneeling out of laziness, and maybe that person is in a church pew for the first time in years, and maybe they’d never enter a church again if they had an indication of how the curmudgeonly woman behind them is judging them.

Why do I …?

Even as my ever-critical mind has a ready rebuttal in justification of each of my personal peeves, at midnight mass I start to feel their collective ugliness, start to feel like a hypocrite for trying to enter into the worship with apparent piety while maybe missing the message with my liturgical and theological fixations, straining gnats and swallowing camels.

All the churches I attended had beauties worth savoring; none were perfectly as I would have them. This mixed truth is probably inevitable.

The Mennonites, in words and actions, really nail the hermeneutics of the incarnation, and the harmonized hymns feel like home – until more textual butcheries throw cold water on the blissful familiarity, old words and ancient images cleaved by the unforgiving knife of a zealous zeitgeist.

The Catholics, keepers of tradition par excellence (however fiercely we may argue among ourselves about what that actually means), would not and could not sacrifice so many powerful and long-cherished biblical and liturgical images to the whims of zeitgeist – but that doesn’t always stop them from burying the profundity of those images under superficial opulence and subtly inhospitable habits.

And yet, am I getting the point?

The humility of the incarnation humbles me, and passing connections remind me that we’re all fellow travelers. How deeply that lesson sinks in remains to be seen.

Incarnate Word, show me what truly matters.