Last Friday’s post on minimum wage laws drew a fair amount of criticism. Which is not surprising. To many people, saying that one opposes a minimum wage law is something akin to saying you support legalized slavery. The idea that such laws might actually hurt the very people they are designed to help is not one that normally occurs to most people, and it’s understandable that many folks would greet the idea, when they do encounter it, with a skepticism bordering on outright hostility.

In any event, there was one objection raised to my post I believe warrants further comment, namely that it is somehow improper, unideal, inconsistent with Catholic Social Thought, or otherwise wrong to think of labor as a commodity.

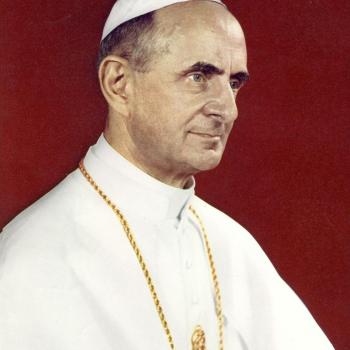

I confess that I do not quite understand the nature of the objection. A thing is a commodity, generally speaking, to the extent that it can be bought or sold on the open market. Is the buying and selling of one’s labor somehow contrary to Catholic Social Thought? Certainly not. As Pope Pius XI stated in Quadragesimo Anno, “those who declare that a contract of hiring and being hired is unjust of its own nature, and hence a partnership-contract must take its place, are certainly in error and gravely misrepresent Our Predecessor whose Encyclical not only accepts working for wages or salaries but deals at some length with it regulation in accordance with the rules of justice.” QA 64. Indeed, the whole notion of the just wage, which is central to Catholic Social Thought, only makes sense on the assumption that labor is a commodity that can be properly exchanged for a set wage. Likewise, minimum wage laws do not prevent labor from being treated as a commodity, but rather presuppose that it is to be treated as such.

To be sure, as a commodity labor does tend to behave somewhat differently than many other sorts of commodities. For example, while the general trend for many commodities has been to fall in real price over time, the opposite that tended to be true of labor, at least for the last several hundred years. As the economist John Nye has noted, “[i]n many countries around the world, even the middle classes can afford to have live-in maids. As incomes rise and the opportunity cost of performing menial labor changes, fewer people will want to work as servants. Those that do will command a higher price. So in America the middle and upper middle-classes are less likely to have servants than in much poorer nations.”

The reason for this trend is that through specialization and technological advancement labor has become much more productive and hence much more valuable to employers. It is this fact, rather than any collective action on the part of government or unions or any moral suasion on the part of Churchmen that accounts for the massive rise in wages over the last 100 years. Presumably, though, when people say that labor isn’t a commodity they aren’t referring to its tendency to increase in price as it rises in productivity, as this would serve to undercut, rather than bolster, arguments in favor of minimum wage laws.

There is also a human dimension present in the market for labor that isn’t present with many other commodities. Paul Krugman put the matter aptly: “A merchant may sell many things, but a worker usually only has one job, which supplies not only his livelihood but often much of his sense of identity. An unsold commodity is a nuisance, an unemployed worker a tragedy.” It was this dimension of human labor that was used by Pope Leo XIII in Rerum Novarum as the basis for the Catholic teaching on the just wage:

were we to consider labor merely in so far as it is personal, doubtless it would be within the workman’s right to accept any rate of wages whatsoever; for in the same way as he is free to work or not, so is he free to accept a small wage or even none at all. But our conclusion must be very different if, together with the personal element in a man’s work, we consider the fact that work is also necessary for him to live: these two aspects of his work are separable in thought, but not in reality. The preservation of life is the bounden duty of one and all, and to be wanting therein is a crime. It necessarily follows that each one has a natural right to procure what is required in order to live, and the poor can procure that in no other way than by what they can earn through their work.

RN 44. The fact that labor markets have this dimension gives them a particular moral importance, and may even justify some form of government intervention (if it could be shown that such an intervention would serve to alleviate rather than exacerbate the problem). But it does not exempt labor markets from the law of supply and demand, any more than the fact that human life is sacred serves to render poison ineffective. However much we wish it were not so, our wishing cannot change the fact that, to quote Krugman again, “the labor market will not function well unless it is allowed to behave more or less like other markets.” Far from showing them to be irrelevant, the human dimension involved in labor markets make the economic arguments against the minimum wage even more pressing.