In 2005, novelist David Foster Wallace gave a university commencement speech that began like this:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

Wallace immediately seeks to reassure his readers that he is not assuming the role of the big fish giving advice to the little fish. Instead, he is simply seeking to make his audience conscious of realities they normally take for granted. As the speech goes on, he discusses the basic self-centeredness inherent to each of us, the default settings we need to overcome in order to empathize with others.These are so basic to our human nature, he says, that we normally do not even think of them.

As citizens of Minneapolis and other US cities take to the streets to protest the brutal death of yet another unarmed black man, George Floyd, at the hands of a white police officer, one terrible truth is yet again made clear: for people of European origin living in the United States of America, racism is the water we swim in. While its victims cannot ignore it, those who stand to benefit from an unjust system all too often cannot see the injustice until it is explicitly pointed out.

In late 2016, soon after Donald Trump was elected to the highest office in the land, a number of hate crimes broke out across the US. As I read about harassment and violence perpetrated by whites against people of color, I was shocked. “Is this really my country?” I wrote, lamenting on social media. “Do these terrible things happen here all the time?”

“You may never know,” a Mexican-Canadian friend responded. “You’re white and you don’t have an accent. If they happen, these things won’t happen to you.”

For as long as I can remember, I’ve watched European-Americans bristle with defensiveness whenever racism is mentioned. We are quick to assert our own innocence, to absolve ourselves of individual responsibility for a society-wide problem. Unfortunately, this attitude is a large part of what feeds the phenomenon.

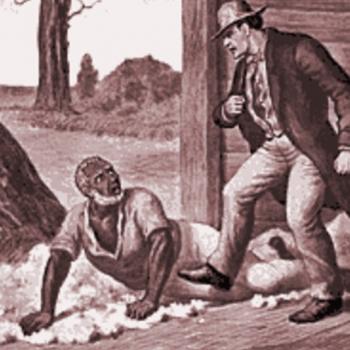

In Octavia Butler’s 1979 novel Kindred, the main character, a 26-year-old African American writer named Dana Franklin, is mysteriously transported across time and space from her Los Angeles home to a Maryland plantation in 1815. She realizes she has somehow been telepathically “called” by a white boy named Rufus Weylin, son of a domineering and abusive plantation owner, to rescue him from drowning. Dana eventually learns that Rufus is her great-great-great grandfather who, after becoming obsessed with a free black woman named Alice, forced her into slavery and concubinage.

In a period of time that for Dana is just a few weeks, Rufus “calls” her several times; she often remains in his world for months at a time or longer while just a few hours pass in her home time and place. As such, she sees him grow up from a small boy into a young man who slowly begins to take on more of his father’s characteristics, culminating in his horrific treatment of Alice.

For me, one interesting aspect of the book is the 1970’s Dana’s marriage to Kevin, a European-American writer twelve years her senior who clearly loves her, having been disowned by his racist family when he married her. But as critic Robert Crossley astutely observes, Kevin is limited in how much he can truly understand Dana’s situation.

At one point, he is transported back in time with her, and they are unfortunately separated, forcing him to stay in the antebellum USA for five years without her. While he does become an abolitionist, there are also moments when he bears an uncanny resemblance to both Rufus and his father. Though subtle, this dynamic of inequality plays out in his 1970’s life with Dana. This reality does not discredit his good intentions or undermine his love for Dana. But it reveals the unsavory truth that most if not all European-Americans have unconsciously internalized racism to one extent or another. It has become the water we swim in, and like David Foster Wallace’s fish, we usually do not even notice it.

A century and a half after the end of slavery, more than fifty years after the Civil Rights movement, we can see that racism remains alive and well in the United States. The death of George Floyd is emblematic of a conflict that remains unresolved – a conflict based on gross inequalities of power. Black Lives Matter is a new civil rights movement with complexities that parallel its 1960’s precursor. No one knows what the outcome will be, but we all will be affected.

It’s a common cliche to stay that the first step toward solving any problem is recognizing the problem’s existence. For too long, so many European Americans have reacted to the legacy of slavery and ongoing reality of racism by relegating it to the past or seeking to deny our own complicity. This needs to change. Seeking knowledge is the first step, followed by discernment and action. If we want reconciliation, we must begin with the truth, and as Pope Paul famously stated in 1972, “If you want peace, work for justice.”