By Fred Smith

As president of The Gathering—a community of individuals, families, and private foundations making financial gifts to Christian ministries around the world—for some time now, I often wonder if philanthropy is one of those words that has either lost its traditional definition (love of mankind) or never should have been used to describe giving in the first place.

In fact I wonder if our use of “love of mankind” actually is possible or even desirable. Yes, there are numerous examples where giving springs from sincere feelings about the poor or a genuine desire to alleviate suffering, spread the gospel, deliver health care, rescue young girls and boys from the bondage of trafficking, and restore dignity to people. No doubt these are good things. But are they really philanthropy? Are they charity? Are those actually two different things?

Jeremy Beer would say they are. Writing in The Philanthropic Revolution, a short, well-organized, and thorough  discussion of charity and philanthropy, Beer traces the history of both and comes to a reasoned (although sometimes testy and sidelong) conclusion: philanthropy and charity, while springing from the same root, have parted ways and are not likely to come back together. While both have serious theological presuppositions, they represent very different—even competing—theologies.

discussion of charity and philanthropy, Beer traces the history of both and comes to a reasoned (although sometimes testy and sidelong) conclusion: philanthropy and charity, while springing from the same root, have parted ways and are not likely to come back together. While both have serious theological presuppositions, they represent very different—even competing—theologies.

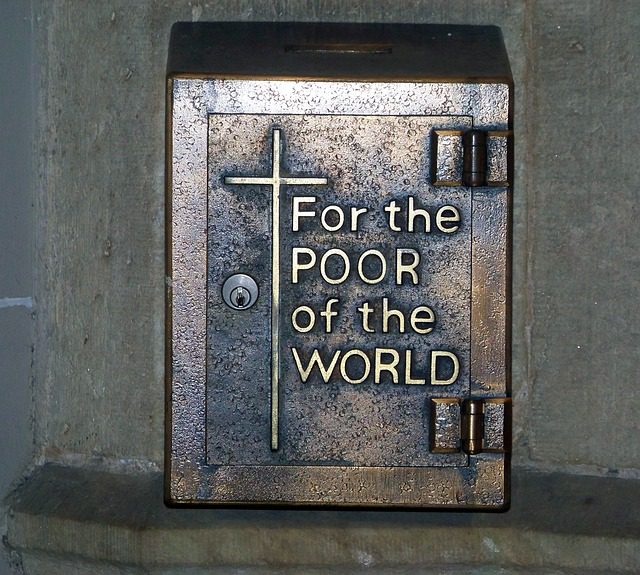

Historically, for Jews and Christians, charity, as the spiritual practice of almsgiving, was salvific and redemptive. “For them, to give generously from one’s wealth to the needy was not merely an act of civic piety; it was to ‘lay up treasures in heaven,’ and thus it had the deepest and most lasting personal significance possible.” Charity was not a way to solve social ills but to alleviate suffering. Charity, like mercy, recognizes that all of life is a gift and that, like God, we give in turn to others. It is not a means to an end.

The poor and the suffering are not a problem to be solved. Rather, charity is an expression of sheer gratitude and human compassion toward another person. “No matter how important its acts of charity may have been in winning adherents, the early Christian church did not view these acts first through a utilitarian lens,” Beer emphasizes. “Charity was not a means, at least not primarily, of solving a social problem, redistributing wealth, or even growing the church. To practice charity was to make a statement about the world and the God who had created and redeemed it.” Charity originated with the Creator and, in turn, pointed back to him.

But, like everything, theology evolves. While the Reformation had the positive effect of eliminating many of the less desirable aspects and practices of the Catholic Church, it had negative consequences as well. Instead of charity being linked to personal salvation, the Reformers held that good works, including charity, had no saving merit whatsoever. Salvation was by faith alone, and almsgiving therefore no longer played a special role in putting the believer in contact with God.

“In other words,” Beer comments, “the person engaged in an act of charity or work of mercy was no longer engaging in a ‘merit-worth deed,’ for he or she could win no merit with God by his or her works.” While the Reformers certainly did not intend it, their rejection of redemptive almsgiving frayed one of the primary cords by which charity was tethered to traditional Christian (Catholic) theology.

For several centuries the two theological cousins—meritorious giving and unmerited favor—traveled along the same path. While some differences, like attitudes toward begging, were the cause of disagreements, both Catholics and Protestants focused on the inherent value of charity. However, during the Enlightenment and immediately following, the path forked. For Benjamin Franklin “traditional charity—giving alms—was self-defeating; the money would be here today and gone tomorrow, and the poor would be as dependent as ever. By contrast, philanthropy removed the conditions it addressed; in its successful wake, charity would go out of business.”

This new idea of putting charity out of business started people thinking about charity itself as a business—a business that would harness the momentum of optimism in the radical improvement of the human condition. Charity would be an effective tool in the project.

Nearly all the antebellum reformers, in fact, believed that it was possible not only to change the world, but also to perfect it, and they spoke of their work interchangeably as benevolent or philanthropic rather than simply charitable. In other words, modern philanthropy’s focus on getting at root causes owes much not only to the Enlightenment tradition represented by Franklin but also to the evangelical movement represented by Finney, Lyman and Henry Ward Beecher, Timothy Dwight, and other prominent figures associated with the Second Great Awakening.

Ironically, the Great Awakening itself and the globally focused millennial beliefs of the evangelists were instrumental in the unraveling of the theological cord that bound Catholic and Protestant understandings of charity. Philanthropy (or what Beer calls “scientific philanthropy”) now found a broader mission to eradicate the very causes of the woes of the world.

With this understanding of philanthropy in place, “the term charity was rejected as denoting something too condescending and demeaning for respectable people to receive—and perhaps as something dangerous for a self-respecting person to offer.” In fact, it was outright scorned as detrimental and counterproductive, an embarrassment to those who wanted to compel the poor to change their moral habits. It appeared to be an excuse for laxness and a failure to make needed change. One critic of charity, Orestes Brownson, was a committed reformer himself but changed his views radically after a conversion experience. “The universal lust to reform society,” he said, “to reform other people in a spirit of ideology rather than faith, must at the last come to this. . . . Love me as your brother, or I will cut your throat.” Brownson feared that radical humanitarians would “make war on the people in order to perfect mankind. Their vaunted altruism was the opposite of genuine love and charity—for it often veiled pride and the will to power.” For this reason, Brownson concluded, Satan’s “favorite guise in modern times is that of philanthropy.”

He had reason to fear the worst. Experimentation, eugenics, mass sterilization, and, ultimately, ethnic cleansing all have their roots in the early (and often forced) optimism of philanthropy detached from both merit and favor alike. The poor became a problem to be solved by institutions with little interest in the individuals they were trying to reform. As Proverbs says, “There is a way that seems right to man but leads to the ways of death.”

Developments like these gave the term “philanthropy” an ironic hue and cut it off from its roots in the love of mankind. Unhooked from its “brotherly” (phileo) concern, such “love” becomes something else entirely. For some, it is now “love of solutions” or “love of fixing intractable problems” but not true phileo—the love of someone with whom you share an interest outside of yourself. As C.S. Lewis puts it in The Four Loves, it’s not so much love of the other person (and certainly not mankind in general) but a love of something shared in common.

Philanthropy, to exist at all, requires a relationship with another person. But philanthropy has become extraordinarily knowledgeable about people while detaching itself from them. In Inc. magazine, Timothy Askew writes about this mindset among young entrepreneurs: “Even in their publicly bruited avowals of pro bono concern for the future of mankind, there seems somehow an unattached sense of being personally outside humanity—above humanity more than part of it.”

As I read Beer’s description of modern philanthropy’s detachment from humanity, I was reminded of The Great Gatsby. Deeply embarrassed by his “shiftless and unsuccessful farm people,” Jay Gatsby reinvents himself and becomes “a son of God . . . about His Father’s business.” It is not love that drives him. “I wasn’t actually in love,” he says, “but I felt a sort of tender curiosity.” I think Jeremy Beer would agree with that. Philanthropy has become a sort of tender curiosity.

Beer’s proposal is the creation of what he calls “philanthrolocalism.” The word does not easily roll off the tongue. In fact, the more familiar and thoroughly Catholic term would be “subsidiarity,” the belief that social problems should be dealt with at the most immediate (or local) level consistent with their solution. Instead of being objective and detached, philanthropy should encourage the possibilities of authentic human communion.

Rather than removing itself from commitment to persons, philanthrolocalism recognizes that we have a primary responsibility to look after that which is closest to us. Rather than taking a global perspective, it concentrates on local communities. Rather than being merely strategic, it reflects the strength of the moral claims and ties that bind us together. In other words, it might not “change the world,” but it might return us to what we have most deeply in common.

Is his proposal practicable when donors raised as global citizens with fortunes outstripping anything the world has seen turn their attention to philanthropy? Are they likely to embrace primarily their local community and look for ways to establish authentic human communion? Is the local community capable of absorbing the bulk of their fortune? Are all philanthropists motivated by pride and the will to power?

Not likely.

However, Jeremy Beer, like Wendell Berry, John Gardner, and others who have written about the value of belonging and obligation to our particular place, should not give up. They may not change the world, but their love applied will be far more than a mere tender curiosity.

Fred Smith

Fred Smith

Fred is President of The Gathering, an international association of individuals, families, and foundations giving to Christian ministries. This post originally appeared at Comment magazine.