“No religion is an island” – Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, November 1965

Dear Archbishop Justin and Chief Rabbi Mirvis

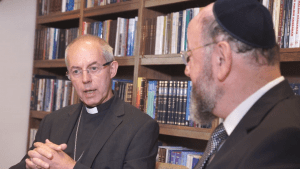

You sat down together in the rabbi’s home in north London just before the Jewish new year. You drank tea and you talked about antisemitism. A few days later, the Church of England’s Bishops’ Conference in Oxford adopted the IHRA definition of antisemitism and the 11 illustrations attached to it.

Your meeting, and the actions that followed, told us much about the moral challenges facing interfaith dialogue between Jews and Christians when it comes to Israel/Palestine.

As a British Jew in solidarity with the Palestinian people and married to an Anglican priest, I have a particular interest in how the institutional conversation between Jews and Christians plays out. What strikes me is how limited that discussion looks to any observer familiar with the concerns of the Jewish community here and Palestinian Christians in the Holy Land.

As matters currently stand, both of you give the appearance of being morally compromised. Watching and listening to you, it feels as if progress – institutionally and theologically on Israel/Palestine – is blocked.

I realise that for Christian leaders, there is a great deal at stake after 70 years of historic progress in Christian-Jewish dialogue. The risk of damaging the trust and friendship built up between Jewish and Christian leaders over decades is too much to contemplate. But the consequence has become a relationship distorted by political considerations.

Meanwhile, on the Jewish side we’re faced with an even greater dilemma: the narrow politicisation of Judaism itself.

Corbyn context

At one level, the Archbishop of Canterbury going to the home of the Chief Rabbi to wish him, and the whole Jewish community, well for the coming year should be welcomed. But, as the video released to mark your meeting showed, it didn’t take long for the real point of your conversation to become clear.

The past year’s allegations of antisemitism made by the Jewish community leadership against the Labour Party and, more precisely, the party’s leader, Jeremy Corbyn, have been unprecedented in modern British history. Chief Rabbi, as you spoke to Archbishop Justin, you adopted the same narrative of ‘existential threat’ to the Jewish community promoted in July by three Jewish communal newspapers over the summer.

Chief Rabbi, here’s how you summarised the situation:

“Ever since the Holocaust we never thought for one moment we would again need to defend our Jewishness, our identity, our existence. It is, to us, unbelievable what is actually happening now.”

“Ever since the Holocaust…” took the conversation to the darkest place in Jewish history, as if this was the only appropriate historical reference point.

If this is how our Chef Rabbi and other Jewish leaders choose to speak, it’s no wonder that some Jewish families will feel anxious and fearful about Jeremy Corbyn and be seriously considering if they have a future in this country.

But such a reference is deeply misleading and highly irresponsible. It’s a deliberate exaggeration of what’s taking place. Chief Rabbi, alongside the Board of Deputies, you have chosen to escalate an important issue within the Labour Party into a full-blown crisis for the Jewish community.

There are, undoubtedly, antisemitic sentiments expressed by some people who are members of the Labour Party. Usually the choice of words is clumsy, sometimes they are deeply misguided, occasionally they’re malicious. It’s nearly always about Israel, typically on social media platforms, and makes the foolish mistake of trading on some very old Jewish stereotypes to explain the behaviour of the Israeli government and its advocates and lobbyists around the world.

But Britain in 2018 is not Germany in 1933, let alone 1938 or 1942.

Archbishop Justin, you chose not to challenge any of the Chief Rabbi’s analysis. I can understand a reluctance to question another religious leader’s perception of the threats to their own community, especially when you are a guest in their home. So instead, you accepted the analysis in full:

“Listening to you, I find it hugely distressing and depressing that in the 21st century any community, especially the Jewish community given the history of Europe and of the last two or three generations, should have a deep sense of insecurity. I think that is appalling; and what that says to me is that the leaders in our nation must be very clear on giving security to the Jewish community in this country.”

Archbishop, you then made clear that “giving security to the Jewish community” boils down to the “leaders in our nation” adopting the IHRA definition of antisemitism along with the illustrations. Although, you added, this is the “start of a journey” and not its conclusion.

Archbishop Justin, you are right to think that IHRA is not the end of the journey. But it’s not much of a beginning either. Certainly not in the context of tackling antisemitism in the Church of England, where there are specific issues hardly touched by the text which you now consider so essential. Nor does the IHRA document help you to balance the concerns of the Jewish community in Britain with what you have heard, first-hand, from Christians living under Israeli occupation in Palestine.

No space for Palestinians

Chief Rabbi, your comments on the video make clear that your primary concern is not traditional ideas of anti-Jewish prejudice but rather the parameters of acceptable debate on Israel:

“It’s when you start engaging in arguments through which you want to prove that [Israel] is a racist endeavour, that the Jews have no right to their own homeland – that is pure antisemitism.

As has been the case throughout the mainstream Jewish leadership’s three-year campaign against Jeremy Corbyn, there is no space allowed for the Palestinian experience of Israel to be heard. There’s certainly no cup of tea on offer for a Palestinian representative at the home of the Chief Rabbi.

The dispossession of the Palestinians and the ongoing discrimination against them play no part in the discussion. It’s as if the whole Zionist programme is only of Jewish concern, only about Jewish self-determination, and affects no other people. Tragically for both Jews and Palestinians, this has never been the case.

Again, Archbishop, you made no challenge to the Chief Rabbi but made this pledge:

“My feeling is, we as a Church need to adopt IHRA formally. I’m distressed that it should be necessary but I think it is necessary.”

So, what’s on show in this seven-minute video which you have given us?

I fully appreciate that the debate around Zionism and antisemitism is where things get extremely difficult for the Church of England – even more than for Labour or any other political party.

The Church as a whole (both Catholic and Protestant) is right to be acutely mindful of its responsibility towards the Jewish people and its deep culpability in creating and spreading antisemitism across Europe and then around the world. That makes calling into question the Jewish attempt to find safety and security through Zionism and the establishment of the State of Israel a ‘no-go area’.

Noble and integral

But it’s not just a self-imposed reluctance on the part of the Church to question the consequences of Zionist thinking.

Making criticism of Zionism ‘off-limits’ in interfaith dialogue has been a priority for mainstream Jewish religious leaders for many years.

Ever since the rabbinical pre-Holocaust objections to Zionism were reversed, the project to merge Zionist thinking with traditional Jewish understanding has been underway. Rabbi Mirvis, you have been an enthusiastic exponent of this. In an article you wrote for the Daily Telegraph in May 2016 you described Zionism as “a noble and integral part of Judaism”.

Once a Chief Rabbi says this, it tends to close down any political or historical debate about the subject. If you are the Archbishop of Canterbury, can you do anything more than just nod your head in agreement?

When this is how Christian-Jewish interfaith dialogue plays out at the highest level, I’m forced to question the real depth of the relationships. How honestly are you communicating with each other? How deep is your theological encounter? Or is this no more than inter-communal politics?

What was most notable about your meeting was that it felt as if both of you were talking about entirely the wrong things, with neither of you addressing the most important issues facing Christian-Jewish dialogue.

So, how do we get the Christian-Jewish interfaith encounter to progress? How can we have conversations that are more honest and challenging while remaining respectful? How can religious leaders reflect current injustices in the Holy Land and current antisemitism within the Church of England?

I hope you’ll accept in good faith my following thoughts to each of you.

Thoughts to the Archbishop of Canterbury

Your Grace,

While we must remain mindful of the past we must not live our lives there. The Church must not lock itself into a straitjacket of perpetual penance as punishment for historic antisemitism. You must feel free to discuss current injustices in the Holy Land with your Jewish partners in dialogue.

Of course, not every rabbi or every Jew is responsible for what has happened to the Palestinian people and their land. That kind of talk is indeed antisemitic. But when defence of Israel and Zionism dominates Jewish-Christian dialogue at the highest level, what happens on the West Bank or in Gaza or East Jerusalem becomes an issue that must be raised in Britain

Heavy heart

Archbishop, in May 2017 when you met the Christian community of the Cremisan Valley near Bethlehem you said:

“You cannot come and hear the testimonies I heard, you cannot hear from the people who live here, without your heart becoming heavier and heavier, and more and more burdened, with that sense of people whose history has led them to a place where all they have known is disintegrating.”

You also spoke of the need for “justice and security” for the Palestinian people and you promised to raise your concerns with “people in power both here and in the UK”.

I believe that you should feel able to share your “heavy heart” with the leadership of the Jewish community. You are well placed, through your longstanding relationship with Jewish religious and communal leaders, to express your concerns without risk of accusations of antisemitism. Safety, security and humanity for Palestinians and for Jews is not a contradictory aim. These needs are not mutually exclusive. It is not a zero-sum game. The Jewish religious leadership could do with your help in finding the language to express this.

A Zionist bind

Your help is needed because Jewish religious leaders in Britain are now trapped in a Zionist bind of their own creation. They feel they cannot speak out against the behaviour of the Jewish State without risking the safety and security of the Jewish people. That’s assuming they recognise (if only privately) that there is a problem to address. Many rabbis sincerely believe that Israel is innocent of any wrongdoing. You should also understand that rabbis are directly employed by their synagogues, so talking about Israel becomes not just an ethical issue but a career consideration.

I sense there a role for interfaith justice-building to replace interfaith silence on Israel/Palestine. There needs to be an ongoing conversation, in private to begin with, which could help find a way back from a narrow, nationalistic outlook as being the only way to ensure Jewish survival. We each have our texts and our traditions to share and explore. And we have our shared faith in a God who did not set out to create divisions and hierarchies. In other words, can we try some interfaith theology instead of interfaith politics?

Poor understanding of Judaism

Archbishop, if you want to address everyday antisemitism in the Church of England, the IHRA text does not offer much in the way of relevant guidance. If you want to grapple with anti-Jewish thinking, there are more obvious matters to consider than Israel/Palestine.

From my own experience of hearing Anglican sermons over the years, there’s a poor understanding of the diversity of Jewish opinion in first-century Roman-occupied Palestine. There’s also little appreciation of the post-Temple development of rabbinical Judaism.

Too many Anglican preachers, despite teaching on Jewish texts each week, present Judaism as one-dimensional, obsessed with ‘rules’ and little changed since the time of Jesus. It may not lead to the “hatred” used in the IHRA definition of antisemitism but it certainly perpetuates a false or distorted impression of what it means to be Jewish and how Christianity should relate to Jews today.

Replacement theology and Christian Zionism

If you’re serious about theologically driven antisemitism within the Church of England, you need to speak out against the two most obvious Christian expressions of anti-Jewish thinking: replacement theology and Christian Zionism.

Replacement theology, as you know, sees Christianity’s new covenant through Jesus as annulling God’s earlier relationship with the Jewish people. It presents a God who has abandoned the Jews ‘as Jews’. Our only true route to God is now through Jesus the Son of God. If you want Anglicans to respect not just Jews as individuals but Judaism as a living, authentic expression of faith, then Christian leaders must teach how that theological accommodation works. That means repudiating replacement thinking.

Some who believe in replacement theology use it as their argument against Zionism. They see the ‘Promised Land’ as no longer promised. But there are far better arguments for Palestinian rights to be respected than replacement theology – for a start, the equality of humankind in the eyes of God.

Meanwhile, we Jews have to think through the meaning of the Jewish covenant too. We must find our own theological accommodation and understanding of the Jewish covenant that does not entail the denial of another people’s humanity. I’ll come onto that in my thoughts to the Chief Rabbi.

I’m quite sure, Archbishop, that you don’t see Jews as mere theological pawns in an end-of-days scenario that will herald the Second Coming. In which case, tackling antisemitism in the Church should mean condemning Christian Zionism. It’s a strand of Christianity that muddles the biblical ‘Children of Israel’ with the modern Jewish nation-state with no attempt at religious, historical or political context. It also proves that it’s perfectly possible to be anti-Jewish and pro-Zionist at the same time.

Jewish leaders around the world, and successive Israeli prime ministers, seem remarkably relaxed about Christian Zionism. They’ve been happy to take the political support and the financial donations while ignoring the divisive theology at its heart. But you should not be so relaxed. Christian Zionists’ claim of friendship for the Jewish people has nothing to do with respect for Judaism. In their final, apocalyptic vision, Jews as Jews must either convert or burn. It’s a theology that leads to unquestioning support for the most extreme versions of Jewish nationalism but has no interest in understanding Judaism on its own terms or taking any account of Palestinian Christians.

Monotheistic, not monolithic

Jews may be monotheistic in our theology but we’re hardly monolithic when it comes to Israel. That creates a dilemma for you in choosing who are acceptable partners in interfaith dialogue. The Chief Rabbi represents only one strand of Jewish practice. The Board of Deputies has no mechanism to represent the tens of thousands of Jews who are unaffiliated to synagogues. Nor does the Board consider Jews who express non or anti-Zionist views to be truly part of the Jewish community. That’s because the Board has become a significant player in the pro-Israel lobby in Britain. It now seeks to determine who does, or does not, have the right to express a Jewish point of view to a Christian audience.

I’ve been personally caught up in this policing of acceptable Jewish discussion, as have many of your bishops and parish clergy. I think you need to call time on the Board’s behaviour. The Church has the right to hear all Jewish voices, not just those officially sanctioned. Otherwise, you are colluding in discrimination against Jews who wish to express a dissenting Jewish opinion. You may want to reflect on the role of dissenting Christian voices in the long story of church teaching on so many social, economic and political issues.

Costly solidarity

Let me finish my words to you by returning to the Palestinian Christians of the Holy Land, and in particular the Anglican community you lead.

Palestinian Christians have made their views clearly known. You’ll be aware of the Palestinian Kairos document published shortly before Christmas 2009. Its full title is “A moment of truth: A word of faith, hope and love from the heart of Palestinian suffering”.

The Palestinian Kairos has provided the spiritual language in which to speak out:

“We condemn all forms of racism, whether religious or ethnic, including anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, and we call on you to condemn it and oppose it in all its manifestations. At the same time we call on you to say a word of truth and to take a position of truth with regard to Israel’s occupation of Palestinian land.”

To “take a position of truth” is to name the racism and discrimination that is so obvious to Palestinian Christians but which Christian leaders around the world are so reluctant to mention for fear of damaging Christian-Jewish dialogue.

Another point of reference would be the Anglican priest Naim Ateek, founder of the Sabeel Ecumenical Liberation Theology Center in Jerusalem and author of Justice and Only Justice. Ateek recently had this to say about Israel’s new Nation-State Law:

“As human beings who believe in democracy for all, we condemn Israel’s new Nation-State law. We call on all our friends to study its racist implications and to resist it through all available nonviolent means.”

Around the same time as your visit to Bethlehem in spring 2017, a statement was issued by the National Coalition of Christian Organizations in Palestine calling for “costly solidarity” in contrast to “shallow diplomacy”. Costly because there is a price to pay and a risk to take for Christian communities around the world.

This was the plea from the coalition:

“That you revisit and challenge your religious dialogue partners, and that you are willing to even withdraw from the partnership if needed.”

I know that many Christian leaders, at a local and national level, greatly value the relationships they have with Jewish leaders and the wider Jewish community. Friendships and mutual trust have been built up over many years. Some of this has been hard won.

But, in the light of the continual and consistent call from Christians in Palestine, these are the questions I believe you should be asking yourself: How do we as Christians express that friendship and trust? What should that trust enable us to say and do?

For Christian-Jewish dialogue to climb to a higher level, both sides must acknowledge the unjust reality of life for millions of Palestinians. Both sides should ask themselves: How should we speak about this truthfully? What responsibility do we have for enabling injustice to continue? What responsibility do we have for ending it?

I have no doubt about how difficult this will be. But nor do I doubt how essential it has become.

Without a new way of talking to each other, the underlying, unacknowledged tensions will grow between Christians and Jews. Perhaps to breaking point. That must not be allowed to happen.

Thoughts to the Chief Rabbi

Chief Rabbi Mirvis,

For the Church of England, Israel/Palestine is just one among many issues it must negotiate. In contrast, for Jews today, and indeed for Judaism itself, Israel and its relationship to the Palestinian people is our dominant challenge in the 21st century.

To speak of Israel is also to speak of the Holocaust. The two most significant events in the last 2,000 years of Jewish history took place in the same decade of the 20th century: the near-genocide of European Jewry and the establishment of the Jewish State of Israel.

It’s hardly surprising that the implications of these two events are still playing out, in myriad ways, more than 70 years later. They have touched every aspect of Jewish life and will continue to do so for decades to come.

We cannot and should not forget the Holocaust. But we must also find a way to end it. We are in danger of passing on to future generations of Jews an endless sense of trauma.

As a minority in the UK, and in other parts of the world, we will always be vulnerable regardless of current social standing or economic success. But there is a very real danger that we become incapable of assessing risks and threats with any degree of proportionality. I fear this may have already happened. Your reference to the Holocaust in relation to antisemitism in the Labour Party only confirms this feeling.

Neither virtuous nor victimless

Zionism was always more than just a project of European settler colonialism. The Jewish connections to the land through our liturgy, our annual cycle of festivals, and of course the belief in the land ‘Promise’ made to Abraham and his descendants, figure large in our religious identity.

I don’t doubt that most Jews still think of Zionism as a worthy and noble endeavour. Not only that, they also see it as the paramount necessity for our long-term safety and security. All other political and ethical considerations become secondary.

Zionism, once a marginal and highly contested political ideology, has succeeded like no other stream of Jewish thinking in our history. So much so, it has undergone a successful merger with Judaism itself. One can no longer see the join. Chief Rabbi, you yourself are a major proponent of such thinking.

But if we continue to think of Zionism as a virtuous and victimless undertaking, it will eventually undo us, both from without and from within. In the end, there is no escaping the role of Zionism in dispossessing and marginalising a people as numerous as ourselves. The sooner we face up to the ethical implications of this, the better. Untangling Judaism from the consequences of Jewish nationalism ought to be a theological priority.

Post-Zionist theology

Just as mainstream Judaism reached a theological accommodation with Zionism after the Holocaust, it’s now time to start thinking about a theological accommodation with ‘post-Zionism’.

Thankfully, Judaism has always been capable of adapting and responding to changing circumstances. The Babylonian exile, the destruction of the Second Temple, life in the ghettos of Christian Europe, the Holocaust, and the political triumph of Zionism – Judaism responded and adapted to all of these challenges.

And now we have a new challenge: an ethical and spiritual crisis caused by the growing understanding, by both Jews and non-Jews, that our project of national salvation has led to an on-going tragedy for another people. And in creating this tragedy, we have failed to provide ourselves with the safety and security that first motivated Zionism.

The crisis is heightened and complicated because it involves us, the Jewish people – a people with a long history of being persecuted by others. The resistance to acknowledging that we ourselves have now become ‘Pharaoh’ is the greatest obstacle to theological progress within Judaism. And it undermines our ability to deepen our dialogue with Christianity.

Think big, be bold

To move forward from Zionism does not entail an abandonment of Israeli Jews. Nor does it mean forgoing our belief in a Jewish homeland, or God’s promises to our biblical ancestors. It does involve a reimagining of those ideas based on the fundamental understanding that God initiated the spark of life with the intent to create a humanity guided by love and justice, not inequality and oppression.

I would encourage you as a religious leader to think big, be bold and question received wisdom. Including the wisdom that says only a ‘Sparta’ state in the Middle East, dependent on the good-will of global empires, will ever be able to guarantee Jewish security around the world.

When Jewish, and non-Jewish leaders, talk of Palestinian “incitement” or “Hamas” as obstacles to peace, you should challenge and repudiate this thinking. Alleged incitement or even rockets fired from Gaza are not an opposite and equal force to occupation, annexation and siege. Nor are Israeli Jews facing an existential threat from Palestinians any more than British Jews are facing an existential threat from Jeremy Corbyn. Chief Rabbi, you need to reject such rhetoric as a deliberate obscuring of the reality of a vastly asymmetrical conflict. It’s time to repair the Jewish moral compass if Judaism is to chart a sustainable path to the future.

A new foundation for Christian-Jewish dialogue

Now that the Church of England has responded to your concerns over antisemitism in Britain by adopting IHRA, how will you respond to Christian concerns in Britain over anti-Palestinianism, whether in British political discourse or in Israeli actions? It’s hardly an unreasonable question to ask considering the emphasis you place on Israel in Jewish life.

It’s time to recognise that a denial of the injustices inflicted on the Palestinian people is undermining our ability to engage with integrity on issues of racism, discrimination and the plight of refugees around the world. These are the very issues to which Judaism and Jewish experience ought to bring considerable learning and authority. As things stand, we look hypocritical.

Chief Rabbi, it should not be difficult to realise that national chauvinism of any kind will always be a threat to our ability to repair a fractured world, build a just society or establish the Kingdom of God.

Solidarity with the oppressed nearly always comes with a cost. That’s because defeating oppression, as Moses discovered, means challenging the most powerful. On this occasion, and in this situation, it is our own people who hold the power. But challenging that power is a cost that’s worth paying. Otherwise, what kind of God are we being faithful to?

A final thought to the Chief Rabbi and the Archbishop

More than 50 years ago, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote the 20th century’s definitive statement on Christian-Jewish dialogue. His lecture ‘No religion is an Island’ now looks like the high-water mark of the post-Holocaust encounter between Jews and Christians. Soon after, it would start to become compromised and corrupted by what Marc Ellis has called “the ecumenical deal”. The State of Israel, which appears not once in Heschel’s lecture, would come to distort the positive post-war relationship.

But Heschel’s words still hold good and are worth returning to within the context of Israel/Palestine. Christianity and Judaism need each other’s support and each other’s critique if each are to progress:

“Horizons are wider, dangers are greater. … No religion is an island. We are all involved with one another. Spiritual betrayal on the part of one of us affects the faith of all of us. Views adopted in one community have an impact on other communities. Today religious isolationism is a myth. For all the profound differences in perspective and substance, Judaism is sooner or later affected by the intellectual, moral and spiritual events within the Christian society, and vice versa.”