This series of posts on St. Joseph has drawn few formal comments to YIM Catholic. But friends have taken me aside, both in person and on line, to say that St. Joseph has attracted their attention. At the end of our visit today, my real-life friend Joan of Beverly noted the remarkable coincidence that devotion to St. Joseph is peaking in an age when the family is under attack more than ever. On-line friends Mujerlatina and Maria have been commenting too. Maria came up with this 100-year-old volume on Devotion to St. Joseph, a treasure I haven’t dug into yet.

This series of posts on St. Joseph has drawn few formal comments to YIM Catholic. But friends have taken me aside, both in person and on line, to say that St. Joseph has attracted their attention. At the end of our visit today, my real-life friend Joan of Beverly noted the remarkable coincidence that devotion to St. Joseph is peaking in an age when the family is under attack more than ever. On-line friends Mujerlatina and Maria have been commenting too. Maria came up with this 100-year-old volume on Devotion to St. Joseph, a treasure I haven’t dug into yet.

The increasing interest in St. Joseph over the past 800 years that I have been detailing is a fascinating case study in how the Catholic Church’s traditions evolve with the times under the influence of the Holy Spirit. If your guiding rule were Sola Scriptura (the Bible is the only authority), you would have little to say about St. Joseph since he has literally nothing to say in the Gospels. But our Church, formed by Christ himself and the first Apostles, led by Peter, takes a broader view.

One of the more interesting testimonies to St. Joseph in recent centuries is the brief account of his early life given by the German mystic and stigmatist Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich (1774–1824). Her four-volume Life of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ is an epic visionary account of Salvation History from Adam and Eve through the death, burial, and Assumption of the Blessed Virgin. It influenced Mel Gibson in making The Passion of The Christ, and it is currently influencing me. I have been reading a little bit of it most days at Adoration, and I’m sure I’ll have more to write at a future date. I hasten to add that Emmerich’s visions are not considered formal dogma or doctrine, any more than St. Teresa of Avila’s visions and voices are highlighted by the Church. But they exist for the faithful to contemplate.

Here’s Emmerich’s brief bio cribbed from the Web link to her book in the preceding paragraph:

ANNE CATHERINE EMMERICH [left] was told by Our Lord that her gift of seeing the past, present, and future in mystic vision was greater than that possessed by anyone else in history. Born at Flamske in Westphalia, Germany, on September 8, 1774, she became a nun of the Augustinian Order at Dulmen. She had the use of reason from her birth and could understand liturgical Latin from her first time at Mass. During the last 12 years of her life, she could eat no food except Holy Communion, nor take any drink except water, subsisting entirely on the Holy Eucharist. From 1802 until her death, she bore the wounds of the Crown of Thorns, and from 1812, the full stigmata of Our Lord, including a cross over her heart and the wound from the lance.

Anne Catherine Emmerich possessed the gift of reading hearts, and she saw, in actual, visual detail, the facts of Catholic belief which most of us simply have to accept on faith. The basic truths of the catechism–angels, devils, Purgatory, the lives of Our Lord and the Blessed Mother, the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the grace of the Sacraments–all these truths were as real to her as the material world. Her revelations make the hidden, supernatural world come alive. They lift the veil on the world of grace and enable the reader to see, through Anne Catherine’s eyes, the manifold doctrines of our Faith in all their wondrous beauty.

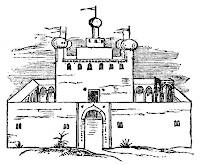

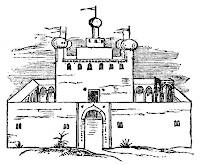

And here is Emmerich’s account of Joseph’s early life. The image below is based on her description of the home he grew up in:

Among many things which I saw today of the youth of St. Joseph, I remember what follows.

Joseph, whose father was called Jacob, was the third of six brothers. His parents lived in a large house outside Bethlehem, once the ancestral home of David, whose father Isai or Jesse had owned it. By Joseph’s time there was, however, little remaining of the old building except the main walls. The situation was very airy, and water was abundant there. I know my way about there better than in our own little village of Flamske.

In front of the house was an outer court (as in the houses of ancient Rome), surrounded by a covered colonnade like a cloister. I saw sculptures in this colonnade like the heads of old men. On one side of the court was a fountain under a stone canopy. The water issued from animals’ heads in stone. There were no windows to be seen in the lower story of the dwelling house itself, but high up there were circular openings. I saw one door. A broad gallery ran round the upper part of the house, with little towers at each of its four corners, like short, thick pillars, ending in big balls or domes on which little flags were fastened. Stairs led up through these little towers from below, and from openings in the domes one had a view all round without being seen oneself. There were little towers like this on David’s palace in Jerusalem, and it was from the dome of one of these that he saw Bathsheba at her bath. This gallery ran round a low upper story with a flat roof on which was another building with another little tower. Joseph and his brothers lived in the upper story, and their teacher, an aged Jew, lived in the topmost building. They all slept in a circle in one room, in the middle of the story which was surrounded by the gallery. Their sleeping places were carpets, rolled up against the wall in the daytime and separated by removable screens. I have often seen them playing up there in their rooms. They had toys in the shape of animals, like little pugs. [Catherine Emmerich uses this word indiscriminately for any creatures she does not know.] I also saw how their teacher gave them all kinds of strange lessons which I did not rightly understand. I saw him making all kinds of figures on the ground with sticks, and the boys had to walk on these figures; then I saw the boys walking on other figures and pushing the sticks apart, placing them differently and rearranging them and making various measurements at the same time. I saw their parents, too; they did not trouble much about their children and had little to do with them. They seemed to me to be neither good nor bad.

In front of the house was an outer court (as in the houses of ancient Rome), surrounded by a covered colonnade like a cloister. I saw sculptures in this colonnade like the heads of old men. On one side of the court was a fountain under a stone canopy. The water issued from animals’ heads in stone. There were no windows to be seen in the lower story of the dwelling house itself, but high up there were circular openings. I saw one door. A broad gallery ran round the upper part of the house, with little towers at each of its four corners, like short, thick pillars, ending in big balls or domes on which little flags were fastened. Stairs led up through these little towers from below, and from openings in the domes one had a view all round without being seen oneself. There were little towers like this on David’s palace in Jerusalem, and it was from the dome of one of these that he saw Bathsheba at her bath. This gallery ran round a low upper story with a flat roof on which was another building with another little tower. Joseph and his brothers lived in the upper story, and their teacher, an aged Jew, lived in the topmost building. They all slept in a circle in one room, in the middle of the story which was surrounded by the gallery. Their sleeping places were carpets, rolled up against the wall in the daytime and separated by removable screens. I have often seen them playing up there in their rooms. They had toys in the shape of animals, like little pugs. [Catherine Emmerich uses this word indiscriminately for any creatures she does not know.] I also saw how their teacher gave them all kinds of strange lessons which I did not rightly understand. I saw him making all kinds of figures on the ground with sticks, and the boys had to walk on these figures; then I saw the boys walking on other figures and pushing the sticks apart, placing them differently and rearranging them and making various measurements at the same time. I saw their parents, too; they did not trouble much about their children and had little to do with them. They seemed to me to be neither good nor bad.

Joseph, whom I saw in this vision at about the age of eight, was very different in character from his brothers. He was very gifted and was a very good scholar, but he was simple, quiet, devout, and not at all ambitious. His brothers knocked him about and played all kinds of tricks on him. The boys had separate little gardens, at the entrance of which stood figures like babies in swaddling clothes on pillars, but sheltered a little (in niches perhaps?). I have often seen figures like these, and there were some on the curtain which hung by the praying-place of St. Anne and also of the Blessed Virgin, but on Mary’s curtain this figure held something in its arms that reminded me of a chalice with something wriggling out of it. Here in St. Joseph’s house the figures were like babies in swaddling clothes with round faces surrounded by rays. In still earlier times I noticed many figures of this kind, particularly in Jerusalem. They appeared, too, in the Temple decorations. I saw them in Egypt as well, where they sometimes had little caps on their heads. Amongst the figures which Rachel carried off from her father Laban there were some like these, but smaller, as well as other different ones. I have also seen these figures lying in little boxes or baskets in Jewish houses. I think perhaps that they represented the child Moses floating on the Nile, and that the swaddling-bands perhaps symbolized the tightly binding character of the Law. I often used to think that this little figure was for them what the Christ Child is for us.

I saw herbs, bushes, and little trees in the boys’ gardens, and I saw how Joseph’s brothers often went in secret to his garden and trampled or uprooted something in it. They made him very unhappy. I often saw him under the colonnade in the outer court kneeling down with his face to the wall, praying with outstretched arms, and I saw his brothers creep up and kick him. I once saw him kneeling like this, when one of them hit him on the back, and as he did not seem to notice it, he repeated his attack with such violence that poor Joseph fell forward onto the hard stone floor. From this I realized that he was not in a waking condition, but had been in an ecstasy of prayer. When he came to himself, he did not lose his temper or take revenge, but found a hidden corner where he continued his prayer.

I saw some small dwellings built against the outer walls of the house, inhabited by a few middle-aged women. They went about veiled, as I often saw women doing who lived near schools in the country. They seemed to form part of the household, for I often saw them going in and out of the house on various errands. They carried water in, washed and swept, closed the gratings in front of the windows, rolled up the beds against the walls and placed wickerwork screens in front of them. I saw Joseph’s brothers sometimes talking to these maid-servants or helping them with their work and joking with them, too. Joseph did not do this; he was serious and solitary. It seemed to me that there were also daughters in the house. The lower living-rooms were arranged rather like those in Anna’s house, but everything was more spacious. Joseph’s parents were not very well satisfied with him; they wanted him to use his talents in some worldly profession, but he had no inclination for that. He was too simple and unpretentious for them; his only inclination was towards prayer and quiet work at some handicraft. When he was about twelve years old, I often saw him go to the other side of Bethlehem to escape from his brothers’ perpetual teasing. Not far from the future cave of the Nativity there was a little community of pious women belonging to the Essenes, who dwelt in a series of rock-chambers in a hollowed-out part of the hill on which Bethlehem stood. They tended little gardens near their dwellings and taught the children of other Essenes. Little Joseph went to visit these women, and I often used to see him escaping from his brothers’ teasing to go to them and join in their prayers, which they read by the light of a lamp in their cave from a scroll hanging on the wall. I also saw him visiting the caves of which one was afterwards the birthplace of Our Lord. He prayed there quite alone, or made all kinds of little things out of wood; for there was an old carpenter who had his workshop near these Essenes with whom Joseph spent much of his time. He helped him with his work and so little by little learnt his craft. The art of measuring which he had practiced at home under his master’s tuition was here of great use to him.

His brothers’ hostility at last made it impossible for him to remain any longer in his parents’ house; I saw that a friend from Bethlehem (which was separated from his home by a little stream) gave him clothes in which to disguise himself. In these he left the house at night in order to earn his living in another place by his carpentry. He might have been eighteen to twenty years old at that time.

To begin with, I saw him working with a carpenter at Lebona. This was the place where he first really learnt his craft. His master had his dwelling against some ancient walls which ran from the town along a narrow ledge of hill, like a road leading up to some ruined castle. Several poor people lived in the walls. I saw Joseph making long stakes in a place between high walls with openings above to let in light. These stakes were frames for wicker-screens. His master was a poor man, and made mostly only such common things as these rough wicker-screens. Joseph was very devout, good, and simple-minded, everybody loved him. I saw him helping his master very humbly in all sorts of ways—picking up shavings, collecting wood, and carrying it back on his shoulders. In later days he passed by here with the Blessed Virgin on one of their journeys, and I think he visited his former workshop with her.

His parents thought at first that he had been carried off by robbers; but I saw that he was discovered at last by his brothers and severely taken to task, for they were ashamed of his low way of life. He was, however, too humble to give it up; though he left that place and worked afterwards at Thanath, near Megiddo, by a small river called Kishon which runs into the sea. Joseph lived here with a well-to-do master, and the carpenter’s work which they did was of a higher quality. Later still I saw him working in Tiberias for a master-carpenter. He might have been as much as thirty-three years old at that time. His parents in Bethlehem had been dead for some time. Two of his brothers still lived in Bethlehem; the others were dispersed. The parental home had passed into other hands, and the whole family had come down in the world very rapidly. Joseph was very devout and prayed fervently for the coming of the Messiah. He was just engaged in building beside his dwelling a more retired room for prayer, when an angel appeared to him and told him not to do this, for, as once the patriarch Joseph at about this time had, by God’s will, been made overseer of all the corn of Egypt, so he, the second Joseph, should now be entrusted with the care of the granary of salvation. Joseph in his humility did not understand this, and gave himself up to continual prayer, till he received the call to betake himself to Jerusalem to become by divine decree the spouse of the Blessed Virgin. I never saw that he was married before; he was very retiring and avoided women.

This vivid account perhaps has no place in this string of posts about the history of devotion to St. Joseph. But it helps me to remember a simple fact: he was a real guy with real parents, brothers, house, and so on.

O blessed St. Joseph, whose holiness becomes only more vivid the more we study and meditate on you, intercede for us!