Christians get agitated when you use the word “cult.”

I found this out recently when I suggested that megachurches can produce a cultish environment, especially if they have a revered celebrity personality for a leader (hence, “cult of personality”). High-control, high-demand, high-secrecy patterns can emerge, leading to all manner of hurt and abuse. Of course, this does not only (or stereotypically) occur within megachurches, but the very suggestion of such produced strong pushback in the comments, on Twitter, etc.

One person on Twitter, a pastor, even said that when people ask if his church is a cult, he just says, “Yes!” – because after all, true Christianity is always going to be considered a cult by somebody.

But both the strong defensiveness and the casual dismissal are characteristic of people who are in denial about the destructive power of actual cults – or, who are currently perpetuating or trapped in one.

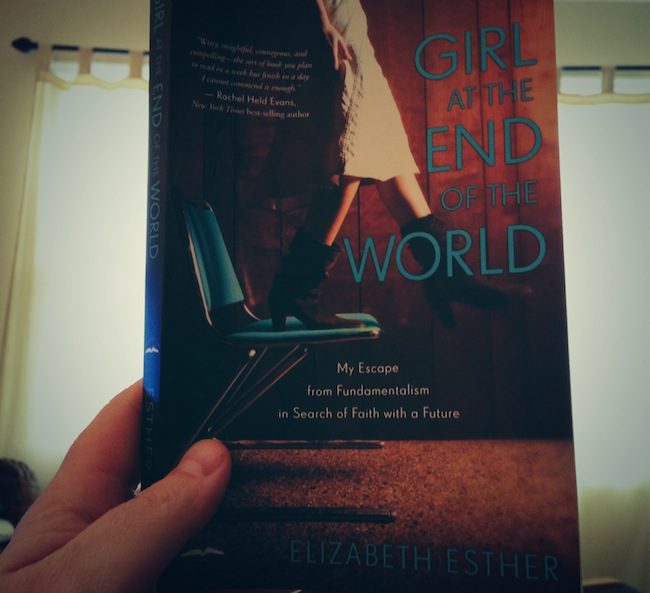

And this is why Elizabeth Esther’s wonderful memoir, Girl at the End of the World, is so important.

This Is My Story

I received a copy of this book last Friday, and I finished it Saturday afternoon. In less than 24 hours, I devoured the story of a girl who grew up in a fundamentalist Christian cult – because that’s my story too. And I began to see the truth of my story even more clearly because of Elizabeth’s courage in telling hers. The fact is, cults are not something that exist only outside of evangelicalism, as if one must adopt a wackier theology in order to be truly abusive. No, as Rachel Held Evans recently said, we evangelicals “have an abuse problem.”

And this book proves it.

Perhaps that’s as good a place as to start as any. If you have grown up in a high-control, abusive church environment and have only disentangled yourself from it in your adult years, you sense an unbelievable risk in telling the truth. There are years – decades – of programmed fear and silence that have to be dismantled before you can even begin to speak out. You have to confront your own ingrained denial. The fact that Elizabeth has even written this book, taking the risk of opening up the lives of herself, her friends, and her abusers and becoming so vulnerable, is a testament to her strength. And, it will likely be a foot in the door for many who are hoping for a way out of cultish evangelical communities themselves.

Elizabeth’s is a tale of lifelong physical, emotional, and spiritual abuse in a post-Jesus Movement church network called The Assembly. Predicated, as many cult groups are, on the imminent end of the world, The Assembly was simply the reality into which Elizabeth was born, with her grandparents the patriarchs and founders and her parents the loyal leadership. Her childhood was a tapestry of end-times fear, indoctrinated patriarchy, street-preaching, daily beating, manipulation, boundary-crossing exposure, and hopelessness. Her young adulthood was a struggle for independence amidst authoritarian control, heavy condemnation, and tactical deprivation/isolation. When she and her husband became parents, the patterns that had simply been accepted as God’s will for them would now impact their innocent little ones. And that’s when the dam broke.

There are differences in the particulars, but this is my story too.

Writing the Way Out

Elizabeth’s writing is just wonderful. Her narrative style translates seamlessly from blog to book, maintaining her signature conversational fluidity punctuated by trenchant humor throughout. In the opening chapters, I was nodding and laughing, remembering the evangelical 80’s. Then, I was grieving, and still laughing – but grieving. By Part Two I was pushed deep into personal reflection and remembrance. In Part Three I was surprised by the sheer grown-up honesty in the irresolvable resolution of it all – and, by hope.

Growing up in a world where the end is near – whether the imminent Rapture of The Assembly or the last-days Great Harvest of my Pentecostal-Prophetic upbringing – is a strange thing. You never really think about what you will do with your life. You are waiting – always waiting. And reading your King James Bible, and sitting in meetings, and staying at home to prove your “distinction” from the world. In Elizabeth’s words, “Verily, verily I say unto thee, none of these highly specialized skills ever got me a job, but at least I’m all set for the End of the World. Selah” (p. 6).

The abuse that then ensues is shrouded in the ultimacy of The End. Nothing else matters except obedience, compliance, loyalty – for then, your future is secure after the Judgment (of everyone else) goes down. Elizabeth’s descriptions of the daily spankings practiced by the cult – really, beatings – are arresting. Perhaps the emotional and spiritual abuse in which they are administered is even moreso:

The next day when I look in the mirror, my bottom is bruised. It hurts to sit down. It hurts to walk. God desires truth in the inward parts, I remind myself. My parents spank me because the book of Proverbs says it will save my soul from hell. Even though Dad says I’m a Christian because I asked Jesus into my heart, the Bible says God chastens His children.

My parents hurt me because they love me. (p. 40)

Thankfully, I didn’t grow up in a home influenced by the same teachings about spanking, so they were relatively infrequent. But the emotional and spiritual abuse Elizabeth recounts is startlingly similar to my experience. At every turn, her desire to grow into her own identity and live out her unique gift and calling is opposed, condemned, forcibly suppressed. She might learn enough to leave, might see a life beyond the family cult. In particular, Elizabeth’s descriptions of her father and grandparents are darkly familiar – so too the anxiety and depression produced by their aggressive words and isolating actions. My heart broke all over again when reading the encounter between Elizabeth and her father in Chapter 11. I have been there.

And when Elizabeth and her husband Matt finally confront the patriarchs over their coverup of domestic violence in the family cult, the same darkness emerges. The darkness of total control tightening its grip. Thankfully, the darkness loses.

I am amazed at the way in which the author has rediscovered her faith in the structure and sacrament of the Roman Catholic Church. Perhaps this is why I’m drawn to a similar expression. Those of us who have survived such things desire safety, accountability, mystery. Not that anything will ever be perfect, but things must be better.

And then, this:

I once heard a story about a woman who asked God to move a mountain. God said okay, and then He handed her a shovel. I think that’s a good anaology for how my story ends. I’m still shoveling. I’m still uncovering, sorting, reexamining. But I’m working on it. And giving it a rest.

I don’t believe in perfect closure. But each day, I can choose to take care of myself. I can choose to let God love me.

He has given me a future and a hope.

I am not afraid. (p. 190)

In Girl at the End of the World, Elizabeth Esther writes her way out of the abuse and oppression of an evangelical Christian cult.

And we should all be grateful for her work.

Thank you, Elizabeth.

Now More Than Ever

If you think this story is an isolated incident or doesn’t happen anymore, you’re wrong.

The patriarch, “Papa” George Geftakys, was only recently exposed over sexual misconduct and covering up domestic violence in the family.

The truth is, if Geftakys’s sexual misconduct and the coverup hadn’t come to light, many evangelical Christians would defend the movement from naysayers like Elizabeth. Elizabeth would be cast as an angry, bitter, unforgiving pastor’s kid who’d just been “hurt by the church” a little bit and needs to get over it for the sake of unity. Likewise, if The Assemblies had gained any prominence in the current evangelical landscape, there would be a host of famous pastors and leaders who would swoop in to explain away the complaints from this bitter PK, and any others who had been abused in the movement. They’d say George Geftakys is fallible like any one of us, and he just needs a little grace. He’s working on things, and he’s a truly humble guy, and we should all be rooting for him and his ministry for the sake of the gospel and God’s glory. Really, just simmer down everyone. Don’t get into all the bottom-feeding gossip and slander.

This has happened before.

It is happening now.

When the recent Sovereign Grace Ministries (SGM) child sex abuse scandal hit, large evangelical organizations were quick to diminish the victims’ testimonies, lean on legal loopholes, and declare solidarity with the movement’s leadership. First there was silence. And then there was participation in what amounts to a damage-control PR coverup.

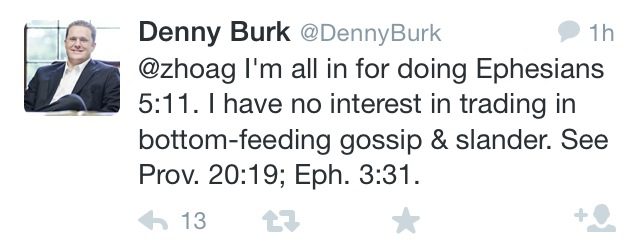

Last week, I had a Twitter conversation with one of the leaders involved in standing by SGM. I asked if he was willing to repent for the institutional coverup surrounding abuse within the patriarchal SGM. He tweeted this:

Bottom-feeding gossip and slander? The testimonies of more than ten victims? The warnings of a respected evangelical anti-abuse organization?

Elizabeth Esther’s story, the story of abuse and secrecy in an evangelical Christian cult, is needed now more than ever.

Selah.