Now Featured in the Patheos Book Club

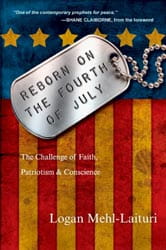

Reborn on the Fourth of July:

The Challenge of Faith, Patriotism & Conscience

By Logan Mehl-Laituri

Logan Mehl-Laituri is an army veteran who speaks and writes broadly about veterans' issues and Christian perspectives on militarism and nationalism. He served in the Iraq War as a forward observer/fire support specialist before applying to change his status to conscientious objector. After his discharge he went to Palestine with Christian Peacemaker Teams, and returned to Iraq with Shane Claiborne for the documentary film The Gospel of Rutba: Christians, Muslims, and the Good Samaritan Story in Iraq.

In this interview, Logan shares about the impetus for writing Reborn on the Fourth of July, and what he hopes people—and especially those in the Church—take away from the book.

Why did you decide to share your story in Reborn on the Fourth of July?

Logan: Stories have power to redeem or destroy. The stories that dominate the broader narratives for soldiers are mostly destructive. We are trained to kill and to experience profound suffering, and the inevitability with which we talk about war leaves little room for hope. When I listen to other veterans, many of their stories are filled with anger and betrayal—at the enemy, but also at the government, their churches or even themselves. I too am angry, but anger is not a reliable theological lens. Despite my anger, "doing" church calls me to faith, hope and love. I wrote this book in faith, with love, as an exercise in hope. "Success" for me will be measured in the number and health of other war-weary warriors stepping out in faith to share their own stories, to interpret their lives more in light of the Prince of Peace than the gods of war.

How do you approach the difficult topic of war and faith?

Logan: Instead of theology from the sidelines, my approach is necessarily one that is heavily invested in the nitty-gritty reality of combat. I try to be honest about the tragedy in war, but also the beauty we catch glimpses of therein and the hope that we find in Jesus. I insist that to deal holistically with war, we must not abstract it from the lived experience thereof. The most important way to learn about war is to hear real accounts of it, accounts that may very well be grotesque. Only after we grapple tangibly and viscerally with the reality of war will we be able to take comfort in the fact that Jesus has saved us, that war is in fact over, if we'll have it. In short, my purpose is to describe the rebirth that occurred in one soldier's life and what is possible in the lives of others, soldiers or otherwise. The military is one way in which to understand the great and abiding joy made possible by the horrific and obscene reality of the cross.

What is your hope for Reborn on the Fourth of July?

What is your hope for Reborn on the Fourth of July?

Logan: The need I am addressing is the lack of firsthand hope-filled tales of contemporary combat that deal seriously with the cruel reality of evil in war. Churches have no lexicon through which to narrate war for those in their congregations who have suffered therein as perpetrators of collective violence. The acts soldiers commit are not their own, but they are tragically forced to interpret and internalize them without much meaningful guidance from religious leaders. There is a moral dyslexia about war that multiplies the suffering our military members endure. With this book, I hope to advance the frontlines of a new and growing space within which we might better process the reality of war through a uniquely Christian lens. More than just an altar call for the church to change the way it speaks of war, this book is a rallying cry for soldier saints, young and old, to muster the courage and strength to share their difficult but valuable experiences for their own good and the good of the church universal.

What do you want readers to take away from Reborn on the Fourth of July?

Logan:

- Veterans and military are not strictly "hero" or "villain," but human. We must not lean so heavily on stereotypes of them as either a monster or a hero. Readers must see the complex character of military formation and practice in order to fully appreciate and "support" the troops. Soldiers are humans, capable of good as well as evil.

- The Bible is not uniform in its depiction of war; it is diverse and multivocal. Soldiering is complicated within the Christian canon; some centurions are celebrated and others are castigated. I try to incorporate Scripture to support both depictions so that readers are challenged to think more critically about the character of Christian soldiers, ancient and contemporary. I also want to register the centrality of Scripture for shaping our understanding of not just war, but those who fight therein.

- The issue of military and national service affects everyone. Underneath the talk of military service is really the conversation about national identity. When churches identify too much with America, they lose their Christian saltiness. On the other hand, when churches identify too much with antiwar sentiments, they often lose their ability to sympathize with, or speak credibly to, this very unique and suffering segment of our population.

- Looking more critically at military formation and cohesion can inform the church and improve its witness. The military teaches the virtues of loyalty and requires courage. The methods and intensity of initial training reflect ancient catechesis. There is a baby in the bathwater of military service that we need to be careful not to toss out. Ron Sider had a point when he asked how compelling the church might be if it were to focus as much energy and resources on Christian formation as the U.S. military does on boot camp.

- We need to "de-fang" polemical discourse on war and peace, to not fall so easily into "patriot" or "pacifist" camps—we need patriotic pacifists and conscientious participants. Putting God above country will look different; it's the understanding that the cross must be more constitutive than the flag, but the flag does have a proper, subordinate place in our lives. Following Jesus while honoring the political order that crucified him will feel upside down, like going to war without a weapon, but it is something we must be able to envision.

- That there is a conversation waiting to happen upon which real lives rely; soldiers, veterans and their families need churches actively engaging in more compassionate dialogue about faith and service. Though I wrote the book fueled by anger and disappointment, I tried to remain honest in interpreting my military experience in Christian terms. I hope doing so illustrates that love really does triumph, that God truly does seek to reconcile all things.

7/1/2012 4:00:00 AM